|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 29.10.2020 | |

|

The Starting Point |

|

|

Alyona Kuznetsova |

|

| Studio: | |

| Evgeniy Gerasimov & partners | |

|

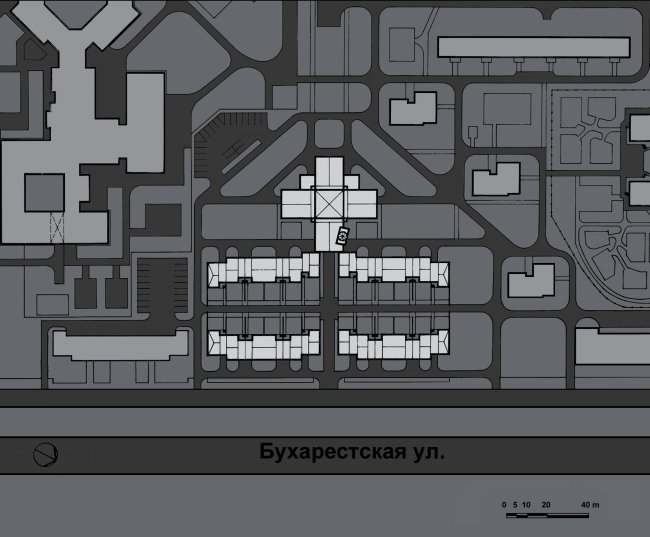

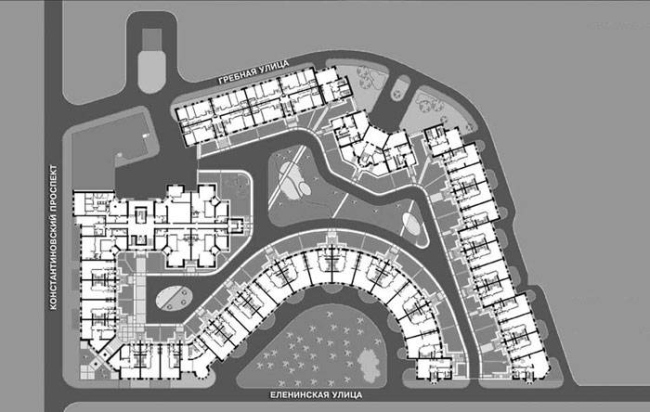

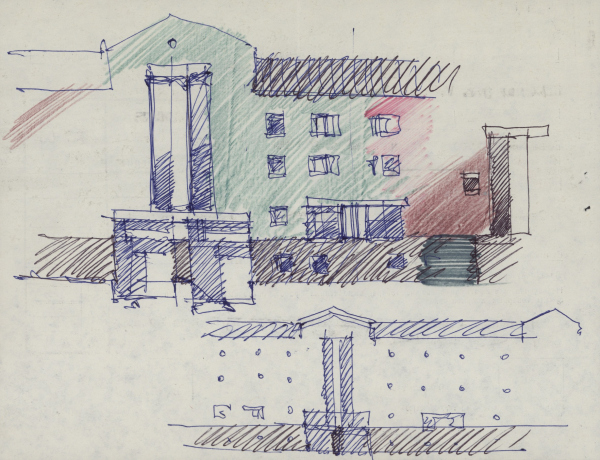

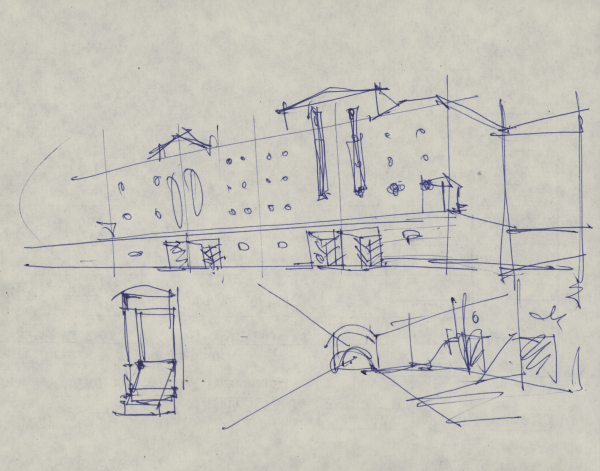

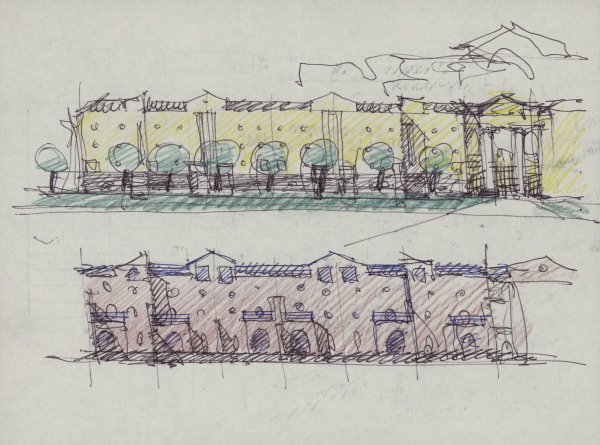

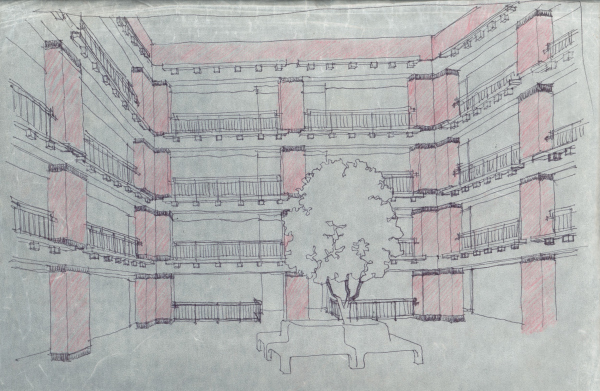

In this article, we are reviewing two retro projects: one is 20 years old, the other is 25. One of them is Saint Petersburg’s first-ever townhouse complex; the other became the first example of a high-end residential complex on Krestovsky Island. Both were designed and built by Evgeny Gerasimov and Partners. Evgeny Gerasimov and Partners is one of the oldest commercial architectural companies in this city; this year its first project – the condominium in Kupchino – is turning 25. Over the next quarter of a century, the company collected a portfolio that is just as impressive as it is diverse: it includes high-end villas in the city’s most beautiful places, grand-scale public buildings, industrial park renovation projects, and neat-looking housing projects at the edge of the city. The company does not limit itself to any particular style, chiefly relying on context and relevance than on fashion trends or a course that has been set once and for all. This approach, characteristic of a “large company”, which is ready to tackle the task of any complexity, could be traced already in its first projects, more of which we are covering below. Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinAt this point, we cannot do without a quick tour of the “primordial soup” of the 1990’s. According to the website , the most significant events of the decade were: the “Freedom of Trade” decree, the opportunity for the citizens of Russia to freely go abroad, the creation of UKOS oil company, the MMM bubble, terrorism, and the default of 1998. In the daily routine, it was the “Broken Streetlights” TV series, vouchers, the Dendy game console, and Michael Jackson performing at Luzhniki Arena. In the professional environment, it was the first Zodchestvo festival and the first articles by Grigory Revzin, the two keywords being freedom and courage. 1. Red Townhouses in Kupchino The company started designing the condominium on Bukharestskaya Street immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1992, and finished it in 1995. From this , the history of the company started. At that time, the young architect Evgeny Gerasimov drew inspiration from the masters of postmodernism, whose works he saw in library magazines – Vittorio Gregotti, Michael Graves, Aldo Rossi – and he would commute to the construction site by Tram 25, carrying around a gas handgun – “times were pretty tough back then”.  Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partnersParallel to the rise in the exchange rate of the US dollar, the Kupchino prefab houses saw the rise of something that was totally sci-fi by the standards of those days – not only in form but in content as well: a castle with fortress walls and a tower, which, upon closer inspection, consisted of US-style townhouses with unseen before heated garages, master’s studies, terraces. The architectural critic Elena Gonzales about this project in 2010:  Elena Gonsales The post-perestroika era split the world of Russian housing construction into two poles: social and “elite”. The appearance of the latter in the 1990’s was brought about by the return of the private property – the millions of dollars that the “new rich” instantly made began to convert in “Euro-remodeling” projects and “condominiums”. What does this mean in architectural terms? Stylistically, this spells the revival of the “bourgeois” classicism in its Victorian version: conservative geometry-based architecture characterized by powerful red-brick walls, turrets, and robust bottom floors. As for the apartment design, it witnessed a veritable revolution that consisted in the appearance of a second bathroom, the so-called “guest” one. Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinThe architects of those days had to invent this new-formation technology from scratch, not having either analogues or predecessors to rely on – apart from photos from the “Architecture and Construction” magazine. Probably, this is why the complex turned out to be so brightly unique; it leaves nobody indifferent even today – people sometimes liken it to a Baptist church, and sometimes to a prison, but it definitely arrests everyone’s gaze. The composition of “Ivanhoe” (this was the name that the condominium got a while later) was designed as a symmetric one. The complex consists of four blocks with six townhouses in each, which are joined into two “walls” running parallel to Bukharestskaya Street and forming a closed rectangular yard. The traversal axis of the yard consists of a promenade and a cross-shaped (on the plan) centerpiece building with “regular” apartments and a “watchtower” highlight. Yet another block, which does not belong to the housing complex, but is designed in the same style, is the building of the Employment Agency of the Frunzensky district; what makes it different from the townhouses are the more habitual and friendly-looking “full-size” windows. One can get the exhaustive knowledge about the rather sophisticated construction of the complex from its . The master plan. Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partnersThe somewhat excessively introverted character of the condominium can be explained by the time when it was built: comfort meant first of all security and privacy. In order to give the residents extra protection from the outside world, which was barging in with the rattling of the morning tram, the architects came up with noise-proof apartment design: the townhouses only face the street with the windows of bathrooms and staircases, while the bedrooms, children’s rooms, and libraries overlook the quiet inner “garden” yard. Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinAlso, from the street side, there is a garage entrance, from which one can get up to their home, while the main entrance is situated from the side of the elevated yard. In each townhouse, there are six rooms, a kitchen, two bathrooms, and a mansard floor, the total area being 140 square meters. The apartments in the “dungeon” have 4 to 6 rooms in them. The apartments are three-sided, with two bathrooms; also, there is an underground parking garage in the building. The turret, which has a staircase inside, is the only element to violate the perfect symmetry: the “eight-on-four” is turned 45 degrees in respect to the orthogonal lines. As Evgeny Gerasimov shared later, “this was a sensual solution meant to enrich the building’s look, and having no conceptual meaning whatsoever.”  Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinAfter many years of mass construction, this project became a challenge for everyone – the architects, the construction company, and even the city people. As was already said, nobody had hitherto heard about parking garages, and the metallic roof was also a novelty; the style that the architects chose was totally experimental. While the striped look of the bottom floors, covered by beautiful multicolored stone, sometimes metallically porous, the broad brick planes, and the “propylaea” of the main entrances all suggest the “fortress” narrative, the purity of the geometric forms, the columns, the cornice, and the trimming around the windows were inspired by Mario Botha. All of these elements are just as laconic as they are paradoxical: laconic cornices with an odd giant cantilevers, and empire windows above the pairs of the verticals of the staircases (originally, the architects designed columns of a “greater” order but it was only a pier that ultimately remained). Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinCondominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partnersIt is rather obvious that the pair of columns on either side of the entrance to the transverse promenade looks very similar to the arch of Saint Petersburg’s New Holland area, even though there is no arch top here – the romantic “castle” narrative is achieved here by very simple means. This is definitely not historicism – the building does not have any specific details – this is nothing but postmodernism, even though devoid of irony but still fresh enough to be different from the “style of the 1990’s”, which will come later on down the line. Condominium in KupchinoCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin2. Green The first high-end residential complex on Krestovsky Island The “Zeleny Ostrov” (“Green Island”) the city’s first high-end residential complex, was built on the Krestovsky Island a little bit later, in 1996-1999, the typology and the overall design being similar: the “perimeter” of townhouses and the centerpiece apartment building. However, while the “fields” of Kupchino were not burdened by the context and could withstand any postmodernist experiments, the Krestovsky Island required attention to its history. “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partnersThe change of location is already felt in the master plan of the complex: its outlines repeat the curves of the streets, carefully stepping back, wherever it is necessary to save the trees. The flowing character of the construction reminds of the proximity of the river and the “accidental” look of natural forms – up until the 1930’s, the Krestovsky Island chiefly hosted , and was not “tamed” by a rigid town planning grid. From above, the plan of the complex looks like a snake, the “head” of which is a building with apartments that goes into the courtyard. A tenement house built in 1909, to which the new building adjoins closely, closing the quarter, as was customary in the central part of the city, does not allow the “snake” to bite itself by the tail. “Green Island” housing complex. Construction, 2000Copyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partnersThe whole complex is divided into five residential blocks, which differ in both facades and layout. The variety proposed by the architects consists of gabled roofs grouped in pairs on the sides of chimneys, hexagonal towers, post-constructivist windows with a column in the middle and recessed balconies with a column at the corner, as well as a “one-legged” portico, which Grigory Revzin was once surprised at back in the day. “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinOn one corner, the house faces the city with a rigid trapeze of the façade, which immediately reminds one of the “fifth corner”. The real highlight here, however, is the rounded façade that is turned to the yard, looking at which one indeed may think that they are looking at a “round” house. “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin“Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinEvgeny Gerasimov shares that this project was inspired by Saint Petersburg dachas of the early XX century. It indeed has a “dacha” look about it – first of all, its height of two or three floors is much lower than the habitual height of the Saint Petersburg tenements of the XIX/XX century, and, if I may say so, reminds the format of Moscow construction of 150 years ago, when Moscow was NOT the capital of Russia. The complex, of course, outgrows the country homes of the modernist periods, but not as significantly as the buildings that appeared on the Krestovsky Island later on, such as “Verona” and “Venice”, also designed by Evgeny Gerasimov, and referring to quite a different style of “palazzo” houses, working with the historical prototypes in all seriousness. On the other hand, Green Island became the first example in a series of high-end houses built on the Krestovsky Island in the following years. The “Green Island” house, in contrast to the red-brick “Ivanhoe” residential complex, is plastered, which gives us yet another analogy – with the above-mentioned post-constructivism that manifested itself in the residential areas of the 1930’s, which have not yet lost their constructivist courage, but have already felt the joy of working with a column. To some extent, it also echoes the houses that were built after the Second World War in Soviet cities by , according to German projects: two or three-story houses, they were usually equipped with pediments that grow out of walls without a cornice; however, similar districts were then built according to the designs of “Stalinist” architects, especially in districts located farther away from the city center. Here, that city looks as if it was taken as an example, and “jam-packed”, due to which the gable roofs became even sharper, and the bay windows grew into turrets, which in turn leads to us perceiving the whole house as a non-classicist one – active, complex, and changing dramatically if viewed from different angles. By the way, this unpredictability, asymmetry and interest in towers were also characteristic of the Kamennostrovsky dachas, so their prototype is probably readable – except that the architects of those days lined up the dachas here, receiving their hybrid with urban development.  “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-Gushchin “Green Island” housing complexCopyright: © Evegeny Gerasimov and partners. Photograph © Andrey Belimov-GushchinThe two houses that we are now remembering – 20-25 years after the completion of their construction – are united not only by the design time and similar techniques. First of all, they are related by a low-rise scale, the mixed “apartments+townhouses”, the presence of direct entrances to houses from the street and front gardens. Subsequently, the townhouse format developed in two directions: affordable and more expensive, but it never became widespread in this country, which is probably a pity. Of course, in the experiments of the nineties there were many things that have long since been rejected by the authors as irrelevant; yet, meanwhile, there were a lot of interesting things in them – and that, with rare exceptions, did not receive development. In particular, the low-rise scale and the interest in experimenting with mixed typology. |

|