|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 09.10.2020 | |

|

A Brick House and the City |

|

|

Lara Kopylova |

|

| Architect: | |

| Stepan Liphart | |

| Studio: | |

|

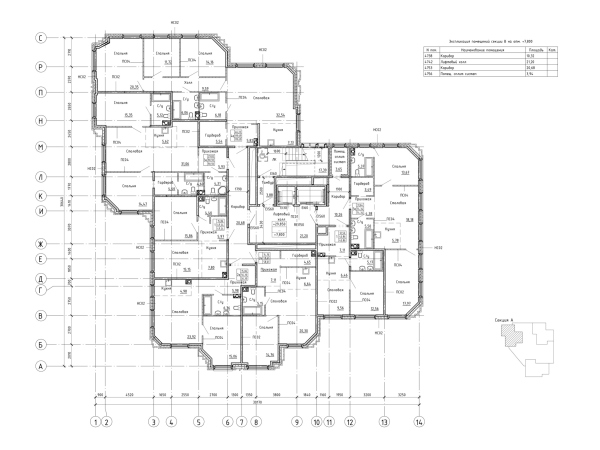

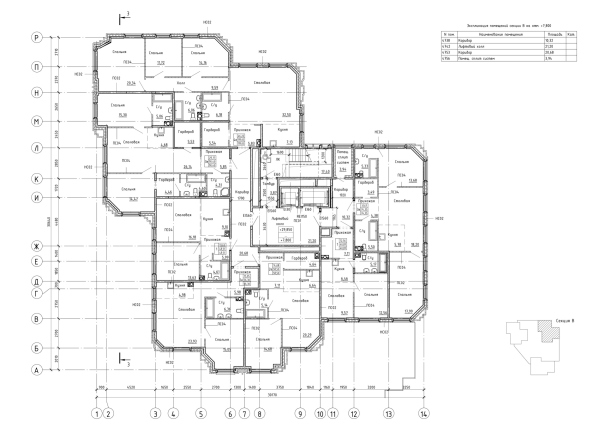

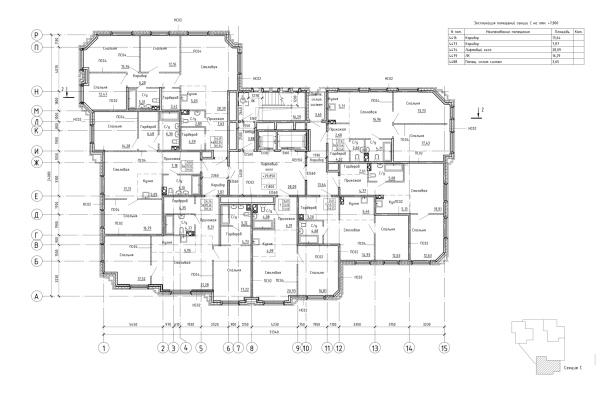

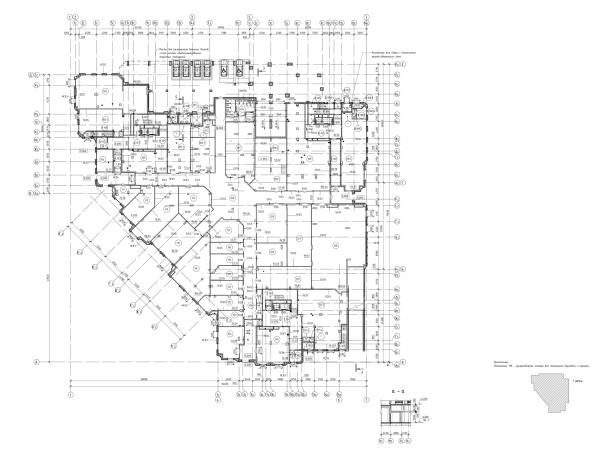

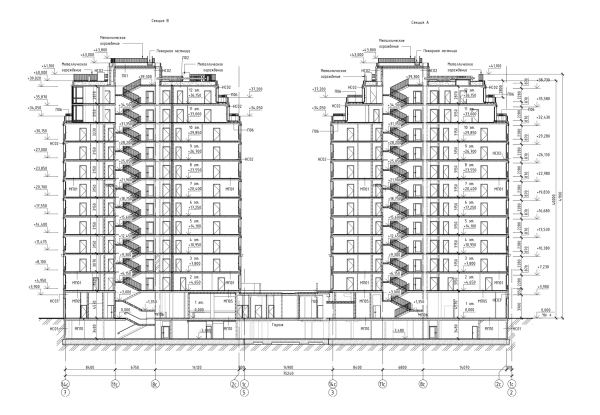

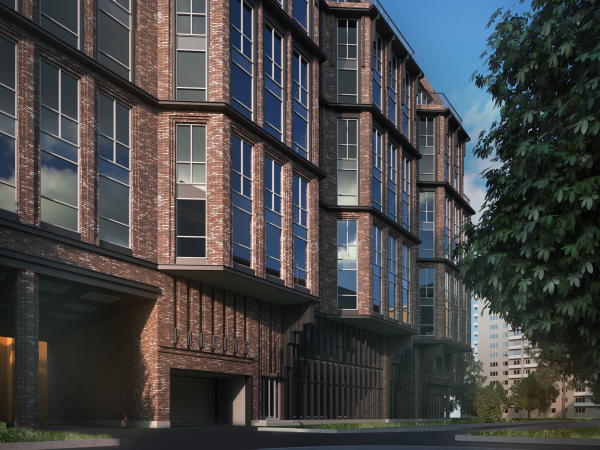

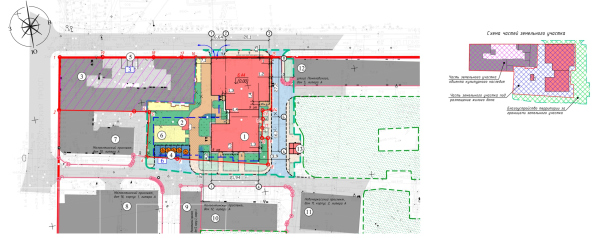

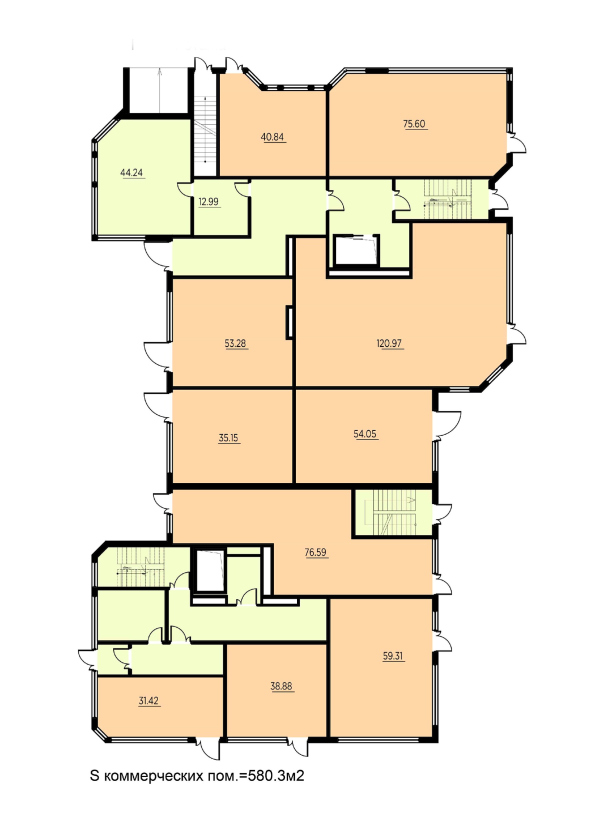

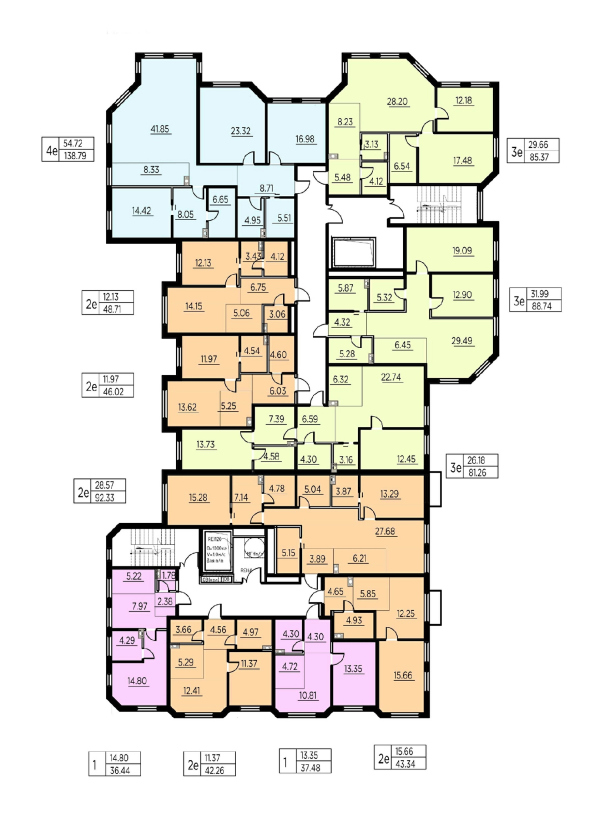

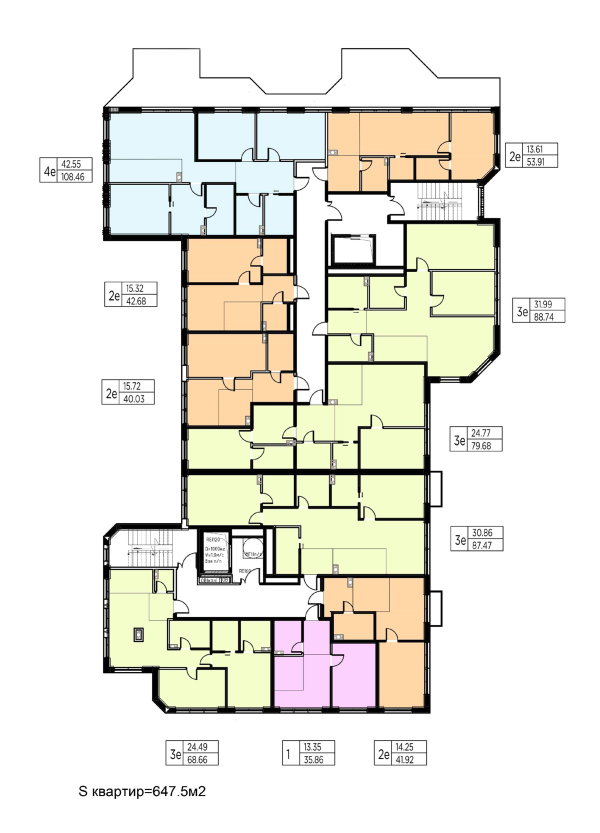

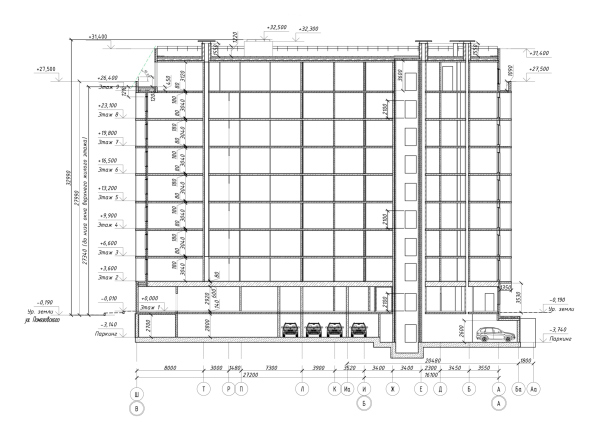

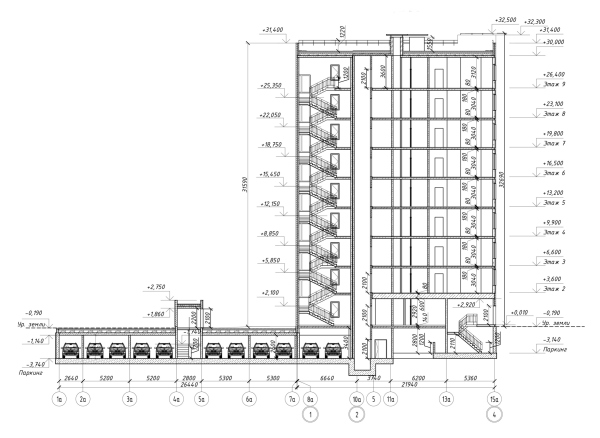

Being fully aware of the romantic and charismatic character of brick architecture, Stepan Liphart invested a fair amount of time into working with the theme of a brick house in St. Petersburg and solved two theorems, proposing towers designed in the style of American Art Deco for the taller housing complex Alter on Magnitogorskaya Street and sensuous Art Deco plastique in a cocktail with loft aesthetics for a house on Malookhtinsky Avenue. Two houses, designed by Stepan Liphart on the Okhta River in St. Petersburg are interesting due to the fact that they continue the idea of a brick house in a modern city. This theme is still relevant; brick is something that appeals to architects and residents alike, and over the last twenty years Russia has seen quite a few successful examples of that. A brick building can be designed in many ways: as a sculpture in the Modernist key, as a mix of loft aesthetics and techniques of modern architecture, and you can also design it in romantic variations of Art Deco, which was something that Stepan Liphart opted for. Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization)The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart ArchitectsThe housing complexes in the area of the Okhta River, on Magnitogorskaya Street, and on Malookhtinsky Avenue have the same common context. These sites lie on the border between the historical St. Petersburg and Soviet Leningrad, in what might be called a “loose belt” filled with both pre-Revolution residential and factory buildings, and the Soviet Khrushchev-era houses. But then again, both houses will command sweeping views – on the other side of the river the city becomes as historical as it gets, represented by the Smolny architectural ensemble and the St. Nicholas Cathedral. The area is very promising; not far away is St. Petersburg’s Artplay, and there is yet another housing project built by a Swedish developer nearby. The main starting point for turning to brick architecture became the shipyard built in 1911, which changed many names, the most memorable of them being “Fabrika Lepse” (“Lepse Factory”), a red-brick industrial building with a tower, predictably turned today into a business center.  Former shipbuilding factory Lepse, now the business center “Shaumyana 10”Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Former shipbuilding factory Lepse, now the business center “Shaumyana 10”Copyright: © Stepan Liphart Former shipbuilding factory Lepse, now the business center “Shaumyana 10”Copyright: © Stepan LiphartThe Alter housing complex on Magnitogorskaya Street While the context for the projects on Magnitogorskaya Street and Malookhtinsky Avenue was similar, the ordeals of getting all the mandatory municipal approvals turned out to be different. Initially, the Alter House on Magnitogorskaya Street was devised by the author in the style of “brick expressionism” (Backstein expressionismus), a variation of Art Deco, characteristic for large-scale German and Dutch buildings of the 1920s, such as Chilehaus in Hamburg or the Anzeiger Hochhaus in Hannover, in which the turmoil of the technological processes of the machine age is already evident, yet the brickwork still sticks to the old techniques of the handmade nature. Romanticism and megalomania on the one side, and intricate fancy brickwork patterns on the other.  CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Clock tower of the town hall in Wilhelmshaven Copyright: Photograph: Christian A. Schroeder / "> CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Clock tower of the town hall in Wilhelmshaven Copyright: Photograph: Christian A. Schroeder / ">Clock tower of the town hall in WilhelmshavenCopyright: Photograph: Christian A. Schroeder / CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Anzeiger Hochhaus in Hannover Copyright: Photograph: Christian A. Schroeder / "> CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Anzeiger Hochhaus in Hannover Copyright: Photograph: Christian A. Schroeder / ">Anzeiger Hochhaus in HannoverCopyright: Photograph: Christian A. Schroeder / Borsigwerke U Bahn station in BerlinCopyright: Photograph © A.Savin, WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0" title="Residential Bremen Water Tower, designed by Wilhelm Kunz Copyright: Photograph: Hannes Grobe / "> CC BY-SA 3.0" title="Residential Bremen Water Tower, designed by Wilhelm Kunz Copyright: Photograph: Hannes Grobe / ">Residential Bremen Water Tower, designed by Wilhelm KunzCopyright: Photograph: Hannes Grobe /The first version of Alter was a house with “bastions”, sporting an asymmetric design following the river bend. The crowning balustrade was decorated with pinnacles in the form of factory pipes – a tribute to the industrial landscape. Generally speaking, it must be said that factory chimneys inspire mysterious feelings in architects: some see in them campaniles (and basilicas in factories), and the English early-industrial landscape of factory chimneys looked to Schinkel like smoldering Egyptian obelisks. Conversely, Stepan Liphart saw the pinnacles as factory chimneys (let’s recall here that Mikhail Belov had pinnacles in the shape of oil derricks). In my opinion, the peripheral pinnacles are the perfect place for technological things, just like gargoyles perfectly match the gutters of gothic cathedrals. The architects, on the other hand, romanticize the factory and, perhaps, feel the energy and vitality in it.  Project of the house on Magnitogorskaya Street. The brick expressionism versionCopyright: © Liphart Architects One of the vesrions of the project on Magnitogorskaya Street in the style of brick expressionismCopyright: © Liphart Architects One of the vesrions of the project on Magnitogorskaya Street in the style of brick expressionismCopyright: © Liphart Architects Project of the house on Magnitogorskaya Street. The classical-style versionCopyright: © Liphart Architects Project of the house on Magnitogorskaya Street. The classical-style versionCopyright: © Liphart ArchitectsAnyway, the romantic Backstein Expressionismus did not get the approval from the main architect of St. Petersburg, and the second, the classical version of the Alter House was not accepted either. Gradually, the housing complex on Magnitogorskaya Street took on the following appearance: three brick towers grouped around a yard, engaged in a dialogue with three white towers designed by another architect, standing close by. Thus, it looks like some kind of dedication. Poets and composers often dedicate their works to some other people, and architects somehow don’t. At least, this is the first instance that I can recall.  Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization) Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization) The site plan. Alter housing complexCopyright: © A-ArchitectsThe three towers are executed in the “ribbed” style of American art-deco. The ribbed corners of the ledges highlight the vertical movement, lines multiply and soar upwards, ending in characteristic rounded edges, like jets of fountains that have reached the climax. The terraces of the three topmost floors rest on these “jets”. Plus, there is also space on the roof for the residents of penthouses. Terraces are a characteristic feature of American Art Deco, while the windows with a fine-fractured checkered glazing pattern are more of the Amsterdam and Hamburg brick expressionism. By the way, all the windows are French, reaching down to the floor, which is nice.  Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization) Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization)In accordance with the accepted structure, the stylobate and the bottom floors will host commercial spaces. On the roof of the stylobate, there will be a private yard with a car park below it. What is curious here is the combination of scales. The scale of the stylobate is one floor, while the lower tier of the towers with pilasters is three floors. While the towers form what night be called a “town-planning territory” – because they are perceived from distant vantage points – the stylobate (with shops and cafes) and the car park entrances are more of the human-friendly scale and the street space. Oh, and by the way, two more public spaces – the waterfront stretching along the historical “Lepse Factory”, through Alter, and further on to the Swedish housing complex, and the yard – will also be landscaped within the framework of this project.  Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization) Alter housing complexCopyright: © Liphart Architects, Mosgraf Agency (visualization) Plan of the standard floor. Alter housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects Plan of the standard floor. Alter housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects Plan of the standard floor. Alter housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects Plan of the 1st floor. Alter housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects Section view. Alter housing complexCopyright: © A-ArchitectsThe house on Malookhtinsky Avenue This house was designed for an even more diverse context: a yellow-and-white classic official building, a Silver-Age tenement, devoid of any decor, and Soviet five-story houses built around the 1960s. There was already a building designed for this site earlier but its solutions did not satisfy the customer. Originally, the new volume was going to be curvilinear, with a complex silhouette, and the architects kept on searching for the optimal composition from the standpoint of insolation and other performance areas. Later on, however, the client decided to return to a simpler form that was set in the predecessor project. All the facades consist of three tiers two floors each, plus a two-story “base” and an attic. Because of the fact that the floors are grouped in twos, a visual effect of decreased height appears: it seems as if there are five floors, while in reality there are nine. The house overlooks the street with one of its side ends, this side end also being the main facade. The composition is held together by two bay windows with a recession between them. The sensuous line of the bay windows refers to a Modernist tenement of the early XX century, and specifically the works by Aleksey Bubyr. One of the proposed versions was a stuccoed one, and in this version the origin was clearly visible.  The house on Malookhtinsky Avenue. The version with wide bay windowsCopyright: © Liphart Architects The house on Malookhtinsky Avenue. The version with wide bay windowsCopyright: © Liphart Architects The house on Malookhtinsky Avenue. The version with wide bay windowsCopyright: © Liphart Architects The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart Architects The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart ArchitectsThe asymmetric recession between the bay windows introduces a slight twist of irregularity in the composition of the main facade. It looks as though a wave washed over its surface, shifting the bay windows off the central axis. In actuality, the bay windows had to be narrowed down so that they would not, in accordance with the effective construction regulations, exceed 30% of the facade surface. The bay windows rest on cantilevers made in the shape of inverted architectons – another Art Deco detail. The brick wall is thinning out as it goes upwards: in the mezzanine, the bulging frames of the windows highlight the mass of the wall, in the next tier, the blades between the windows become thinner, and in the third tier the piers between the windows are partially covered with metallic sheets. This creates an effect of the wall thinning out and gradually losing its mass.  The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart Architects The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart Architects Akzent housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert” The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart ArchitectsA similar effect is also to be seen in the bottom tier, which you cannot really call a “basement floor” because it looks light and actually consists of two floors – one commercial and one residential. These two are visually connected by a glass surface, upon which brick “curtains” fold up and spread out. The yard facade is organized by risalits and bay windows, yet flatter and more regular. From the opposite side, the house sports a rounded projection that looks as if it continues the movement of the wave that starts on the main facade. In the attic, there is a penthouse; the wall is decorated with a ribbed brick pattern.  The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart Architects The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert” Akzent housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert” Akzent housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert” Akzent housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert” Akzent housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert” Akzent housing complexCopyright: © A-Architects and OOO ITs “Stroyexpert”It expected that the house will be decorated with exquisite Klinker brick; the windows that it has are of the modern “loft” kind, with dark-gray aluminum frames, which effectively means that an industrial loft in its most attractive brick aspect has been crossed with the expressive plastique of the Silver Age tenement. Other things that come to mind include experiments with bay windows in brick expressionism and in the development of the Petrograd Side of the 1920s. Evidently, combining a brick loft with traditional architecture turned out to be quite a fruitful idea. For example, in Moscow’s Rassvet LOFT Studio the industrial aesthetics was superimposed on a New Urbanism technique, where the facade front looked as if it consisted of a few narrow houses. A cocktail of a brick loft, Art Nouveau, and Art Deco in the house on Malookhtinsky Avenue is also quite convincing. The house on Malookhtinsky AvenueCopyright: © Liphart ArchitectsBoth variations of the brick house proposed by Stepan Liphart look to me very promising in terms of developing the modern city. The creative interpretation of brickwork forms – in the lower tiers – a kind of plastique that is pleasing to the human eye, at the same time making it possible to build as many more floors as you want, should such a necessity arise. A significant part of Manhattan and other areas of New York is built precisely this way. For large Russian cities, where, for objective reasons, it is not possible to create humane 7-8-story buildings, textured bricks of varying degrees of order are an excellent way out. And, wherever the scale is smaller, and the performance indicators do not press the author so much, the possibilities of brick plastique are virtually boundless, which is proven by the project on Malookhtinsky Avenue. P.S. A human being as an artistic task The unity of the human principle and artistic values in traditional architecture was always considered immutable. Idolizing the machine, which occurred in the avant-garde architecture, has led to complete ousting of everything human, which used to manifest itself in order, plastique, and the very “humanity” of the building. This process has been going on for about a hundred years. In the XXI century, the presence of human principle in the poetics of architecture is not just no longer considered obligatory – nobody so much as raises any questions about it. To a certain extent, the “humanity” has shifted to planning and organizing the interiors of the apartments, yet even there it stays purely functional, not covering the spiritual aspects of human life. The factory of the early XX century was a home for a machine, yet it paradoxically retained the human principle in the construction of the brick facade, proportions, silhouette, and window frames. Today, we value and preserve the “pre-avant-garde” brick architecture, but it’s only the shell that we preserve, dealing with the internal space at our discretion. And it’s just beautiful that form did not follow function! In the brick expressionism of the 1920s, the residential building, ironically, became a factory, was filled with industrial romanticism, yet still kept its humanity thanks to the hand-laid brickwork pattern. Today, architects do not ask any questions about the human principle as the artistic task, engrossed in less lofty, albeit just as important issues. For Stepan Liphart, however, this question was the main one when he was studying to get his degree in architecture. It was the human being that became the subject of an argument between the then-student Liphart and the deconstructivist Thom Mayne, and the vector was chosen by Stepan precisely during that time. In his every St. Petersburg project – the housing complexes “Renaissance”, “Beaumont”, and “Little France” on the Vasilyevsky Island, the architect explores the facade plastique, in which the human being is inevitably present. And the two brick houses on Okhta are no exception. Then, of course, the main question remains – Why? Why do we need man in architecture? The answer, at least for a Christian, is very simple. Man is the image of God. By throwing man out of architecture, we also eliminate God from it. What remains is nature and technology, ecological totalitarianism and robotic civilization, which we are seeing in the impending sixth technological order. Art and architecture (if the latter indeed is an art) always predicts the image of the future very accurately. And it’s great that they give us hope. |

|