|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 13.05.2020 | |

|

Cape of Good Hope |

|

|

Alyona Kuznetsova |

|

| Studio: | |

| Nikken Sekkei | |

| MVRDV | |

| Valode & Pistre | |

| UNS | |

| Sergey Skuratov architects | |

| ABD architects | |

|

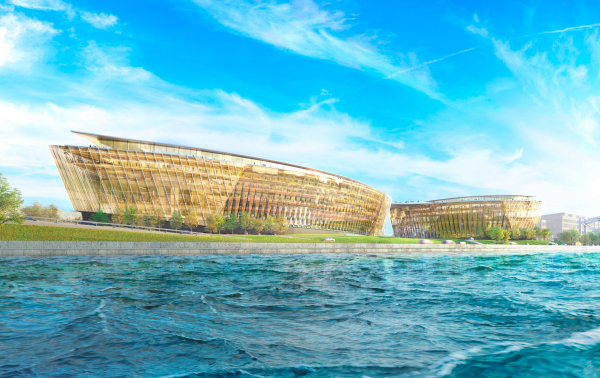

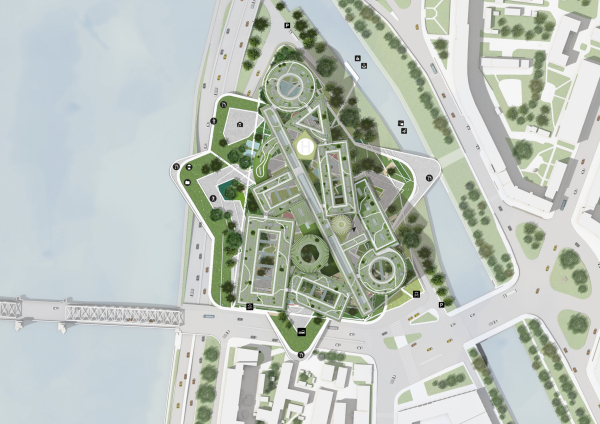

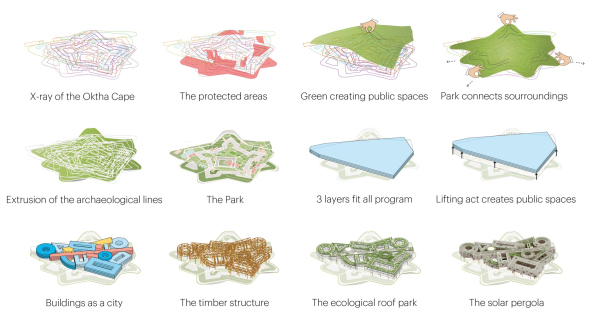

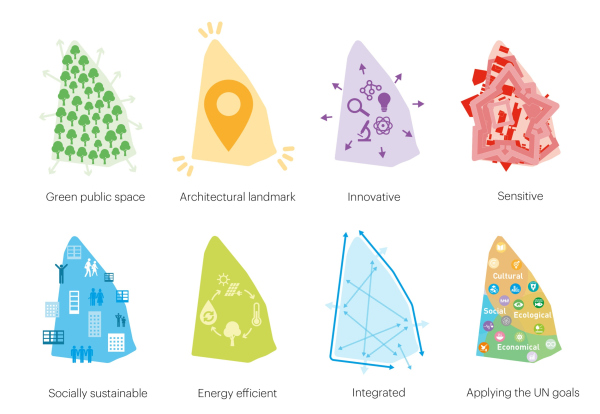

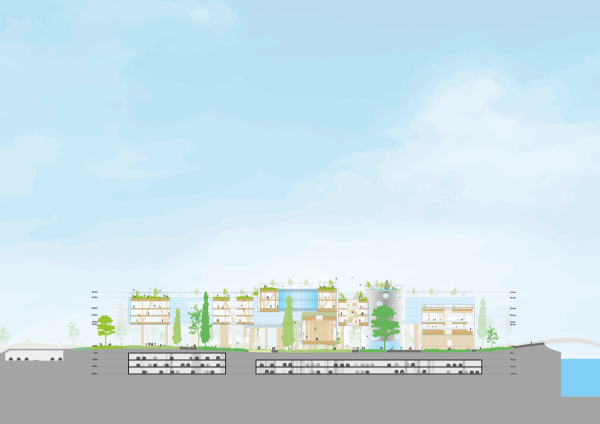

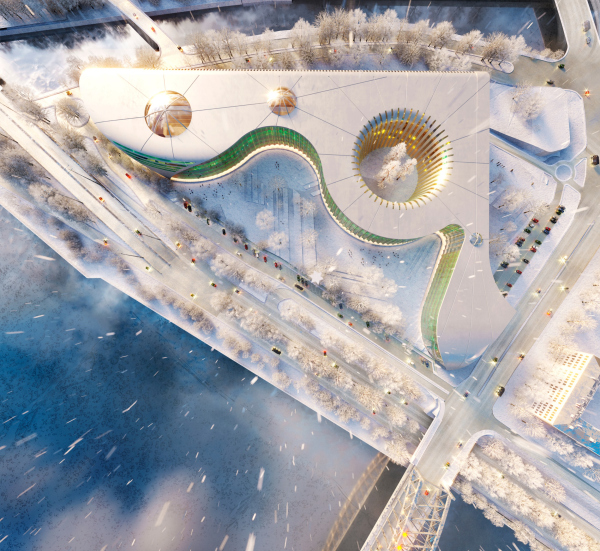

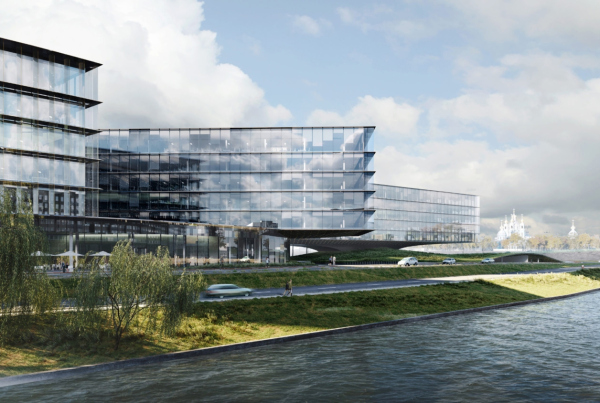

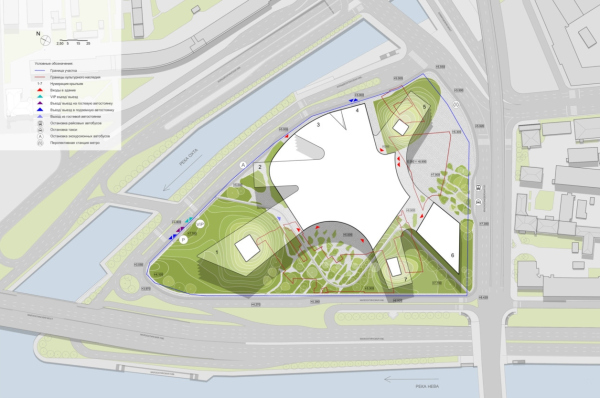

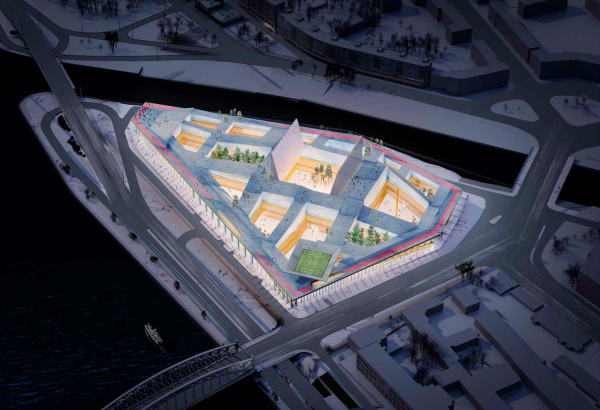

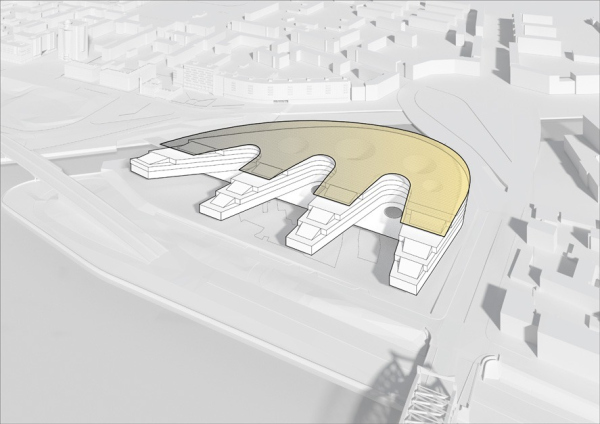

In this issue, we are showing all the seven projects that participated in a closed-door competition to create a concept for the headquarters of Gazprom Neft, as well as provide expert opinions on those projects. In March, the results of a competition for the best concept for the development of the Okhta Cape were announced. Previously, Gazprom Neft planned to build the highest tower in Europe here, and now it intends to place its headquarters on the cape. The competition involved seven architectural companies, four foreign ones reaching the final, the Nikken Sekkei project coming out the winner.  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: The image provided by the Gazprom Neft press service © Nikken Sekkei Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Nikken Sekkei / provided by RBC St. Petersburg Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Nikken Sekkei / provided by RBC St. Petersburg Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: The image provided by the Gazprom Neft press service © Nikken SekkeiCritics of the project note the pragmatism and neutrality of the solution presented by the architects, the lack of intrigue and relative difficulty of implementation. The glass facade is not exactly environmentally friendly, and, in addition, it brings about the phenomenon of pseudo-transparency: despite the “crystal” walls, the building looks monolithic and not really welcoming. Also, there is no clarity about what will be done with the archaeological finds. More about the project -> MVRDV. A finalist Judging by what is written in the information field, this project has been the greatest hit with the public. The sectional volume of the office building, the composition of which resembles the abstractions of Vasily Kandinsky, rests on 119 columns, between which trees grow. According to the project, this “forest”, along with the green roof with its lush vegetation, was to be made fully accessible to the city people. The goals of the Dutch company are quite ambitious: to build the largest wooden building in the world, revive the ecosystem, create a smart work environment, link many contextual threads, from the marshes and the Nyenschanz Fortress to the baroque and Soviet architectural heritage of this area. The latest green technologies provide a “clean” operation of the building.  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The corner view. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The winter view. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV View of the roofs. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Mir The gallery. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The interior. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The park. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The roof. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDVThe project is exciting and intriguing. However, after reading the accompanying “manifesto” note, you can see why it fell short of scoring the first place. “Gazprom – says Winy Maas – is among the world’s top three companies in terms of carbon emissions, and our company is radically committed to sustainable design.” To solve this moral dilemma, the architects came up with a headquarters design that is merged with the landscape, which does not harm the environment and does not use fossil fuel for its support, at the same time doing quite the opposite, i.e. purifying the air of carbon dioxide. Implementing such a project, which does not make a direct statement about the power of the oil corporation, and is in many ways useful for the city, would really be a favorable compromise. However, there are alternative opinions as well. For example, Yevgeny Gerasimov considers the project to be supercilious and argues: one, the trees on the roofs and under the buildings do not grow in our climate, two, blocking the view of the bridge evidences that the architects fail to grasp the fundamentals of urban planning, and, if you remove the greenery, then there will remain a random pile of cubes – and random shapes is something that is totally incompatible with St. Petersburg. This point of view only confirms the need to discuss the future of the cape openly and with the involvement of professionals and the urban community. More about the project ->  Master plan of the 1st floor. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV Master plan of the roof. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The steps for developing the park and the building. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The original vision. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The office levelCopyright: © MVRDV The wooden structure. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDV The section view. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © MVRDVValode&Pistre. A finalist At a glance, the project proposed by the French architectural company surprises with the deliberate design that arises from the contrast between the acute angle and the wavy façade – when viewed from above, the building resembles a segment carved from a giant rectangular block. The contrast, as follows from the explanatory note, reflects the different nature of the Neva and Okhta rivers, the merger of which is another semantic load of the site. From the side of Okhta, the facade is more or less monotonous and calm, like the water of a small river. From the Neva side, there are expressive waves, the bends of which frame the areas with the archaeological finds. Extensive horizontal facades are a tribute to the continuous development of St. Petersburg embankments. And on the “wave” that goes to the Neva, thanks to the glass curves and the play of reflexes, a vertical rhythm is created that echoes the regular rhythm of the colonnades of the historical buildings. According to the authors, the light and color effects are reminiscent of the colors of Russian Baroque architecture, characteristic of St. Petersburg. More about the project ->  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & Pistre Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & Pistre Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & Pistre Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & Pistre Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & Pistre Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & PistreUNStudio. A finalist In this concept, just like in the winner’s, the building consists of two units. These two units are linked by a large “corridor” atrium, which serves as the main entrance and the main public space. The atrium commands a view of the Smolny Cathedral and connects the city with the embankment, at the same time offering venues for exhibitions, events and recreation not only for the city people, but also for company employees. For the latter, comfortable working conditions are created: state-of-the-art climate systems, natural light, co-working and recreational areas, as well as an abundance of vegetation in the interior and in the surrounding areas. The composition is inspired by a pointed plan of the Nienschanz Fortress, the complex glass facades being meant to resemble the edges of a gem enclosed in a pristine frame. The inclined volumes not only create an expressive sculptural surface, but also protect the premises from direct sunlight and overheating. Reflections allow the facade to change depending on the weather and time of day, just like the Neva does. More about the project ->  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © UNStudio Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © UNStudio Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © UNStudio Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © UNStudio Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © UNStudio Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Valode & PistreNext, we show the projects that participated in the competition, but did not reach the final. Sergey Skuratov architects The concept proposed by Sergei Skuratov looks to be the most thought-out one. The company’s website has a lot of pictures and explanations, according to which the symbolic building resembles a neuron with axon and dendrite rays, “a star, a message, and a signal, a radiance, a flash of energy”. The concave facades pick up the St. Petersburg theme of the semicircle, “modifying the initial plan of Voronikhin with two colonnades for the Kazan Cathedral, which was never to be implemented.” Five skylights of various shapes, like bursts on the surface of water, are placed on a flat greened operated roof. The internal spaces should create an illusion that the city is really far away – for this, the authors of the project suggest using decorative plants and crops, which they plan to water with rainwater. The active dynamic facade is able to regulate heat transfer with the external environment. More about the project ->  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS View from the Okhta embankment of the Smolny Cathedral. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The main entrance to the complex from the side of the Kranogvardeiskaya Square. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The roof. View of the Smolny Cathedral. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The main atrium. View of the amphitheater from the bar. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The mater plan. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSKOSMOS The project presented by Kosmos bureau is similar to the MVRDV project in terms of creating a fractional and welcoming building. The Moscow architects, just like the Dutch ones, were inspired, among other things, by the courtyards and roofs of St. Petersburg. The dense volume of the office building is cut through by courtyards integrated into one system, each with its own atmosphere and landscape. The central courtyard can be closed with sliding doors and turned into a concert hall or an exhibition area. The main public space is located on the roof and is comparable in scale to the Palace Square or the Champ de Mars. In this project, the park, which the authors proposed to make available to city people around the clock, commands views of the Smolny Cathedral and the Neva. In it, the architects placed an amphitheater, a jogging trail, a cafe, co-working spaces, and a mini-football field with spectator seats. More about the project ->  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Kosmos Architects Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Kosmos Architects The main courtyard. Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © Kosmos ArchitectsABD Architects in consortium with Ingenhoven Architects Again, a “mono-building”. It is turned to the embankment with four terraced units, between which three areas are formed, and towards the city with a continuous semicircle of the facade. The multi-level “well” atriums host pine trees and other large trees. The building is covered by a transparent roof that lets in plenty of natural light. “The image of the building is an innovative interpretation of the Neva embankments,” the ABD website says. More about the project ->  Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © ABD architects Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © ABD architects Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © ABD architects Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © ABD architects Concept of developing the territory of the Okhta Cape.Copyright: © ABD architects*** The Okhta Cape is a territory as important for St. Petersburg as the Tuchkov Buyan, which has been talked about for the whole past year. Archaeologists have found here the remains of the Swedish fortress Nyenschanz, the Smolny Cathedral is situated nearby, the Neva, the Bolsheokhtinsky bridge are also factors to consider, and all around there is a slurred urban situation: the place is loaded with vehicles and has not been connected with the city for many years. Taking advantage of the quarantine lull, the St. Petersburg public draws attention to the closed-door competition in the hope of revising its results. Architectural critic Maria Elkina launched a requesting a more successful project that could become a “compromise between the interests of the city and Gazprom Neft.” “My petition is ultimately not for a specific project or even for a public discussion for its own sake – it is for revising the agenda around the Okhtinsky Cape and everything that is being built in St. Petersburg,” Maria explained on her Facebook page. Currently, the petition has been signed by more than 2800 people. Some time ago, RBC organized an online conference: joining it is interesting if only to look at experts in a “home” setting – the chief architect Vladimir Grigoryev, for example, spoke with the support of portraits of Vladimir Putin and Alexander Beglov, while the president of the local Union of Architects, Oleg Romanov – from his hunting lodge. Following the results of the conversation, they formulated advice for the client: to look for an intriguing rather than practical architectural solution, to think over a program of public space and traffic flows, to take into account the complex context of the place – with its archaeological values, Soviet heritage and other “baggage”. Vladimir Grigoryev did not rule out the possibility that the project would be considered by the city council. *** Artem Kitaev, one of the founders and partners of Kosmos bureau, shared with us about the competition procedure and specifications. |

|