|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 17.04.2020 | |

|

The Pivot of Narkomfin Building |

|

|

Natalia Koriakovskaia |

|

| Architect: | |

| Alexsey Ginzburg | |

| Studio: | |

| GA | |

|

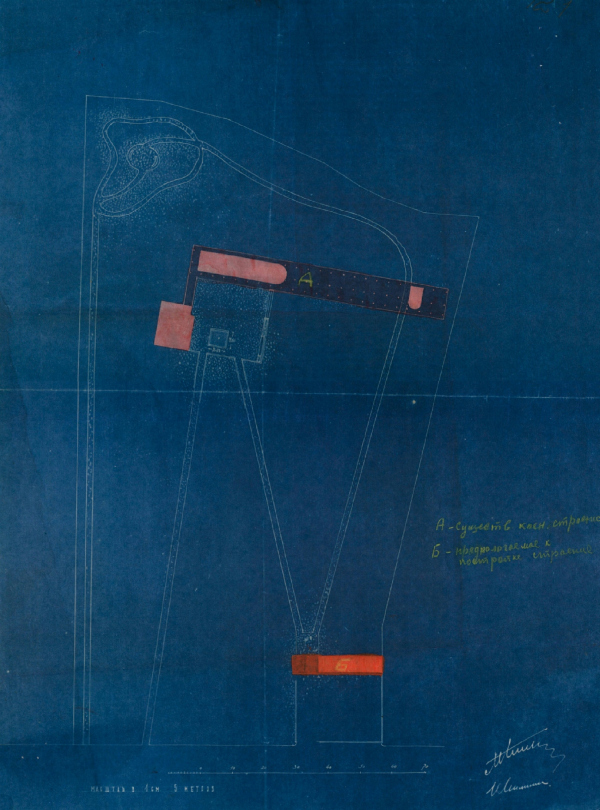

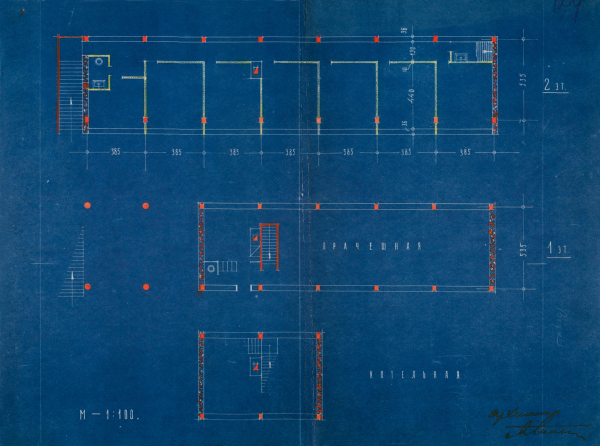

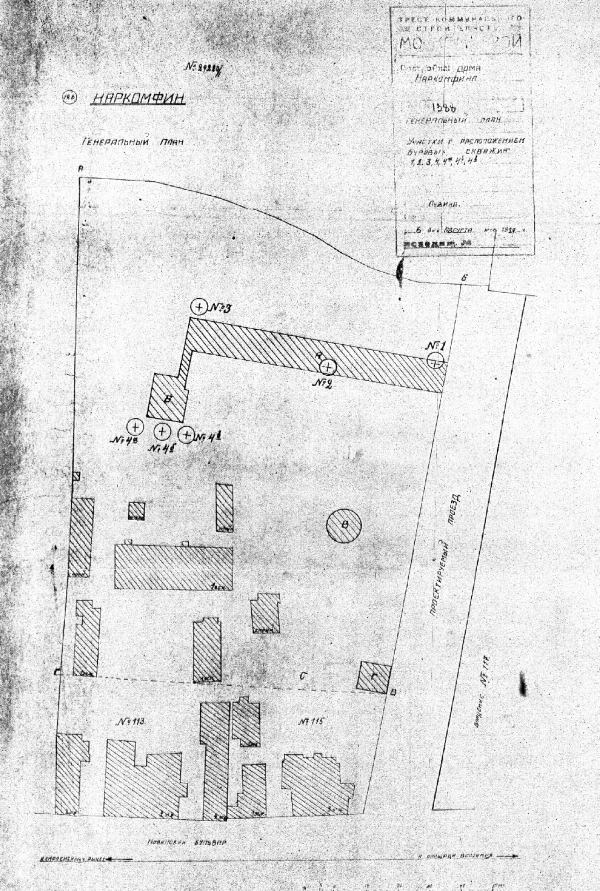

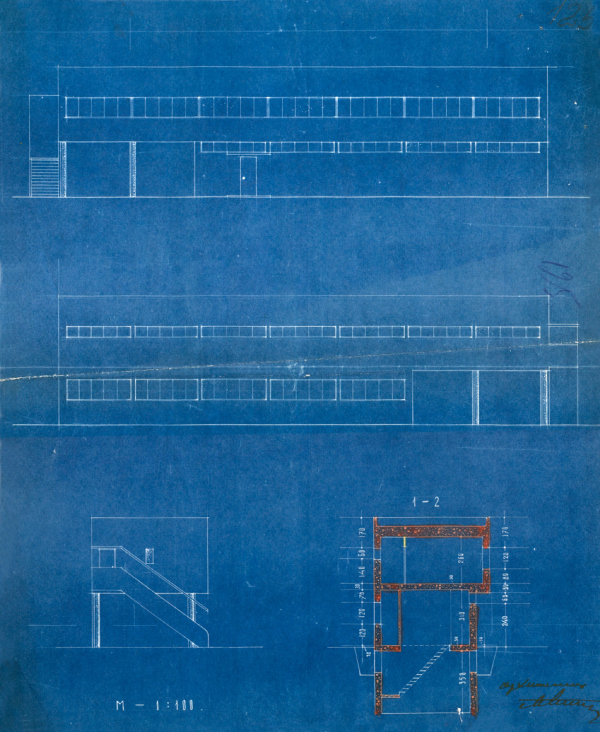

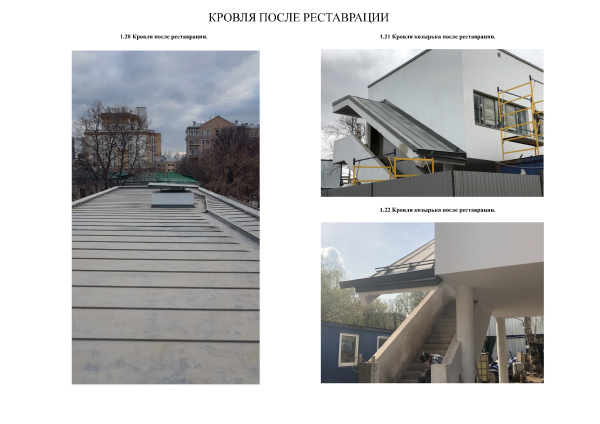

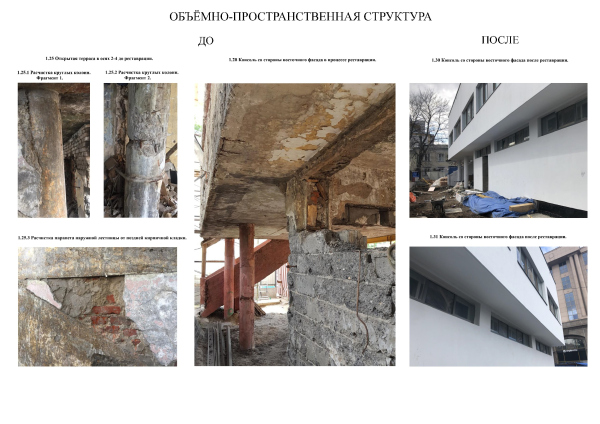

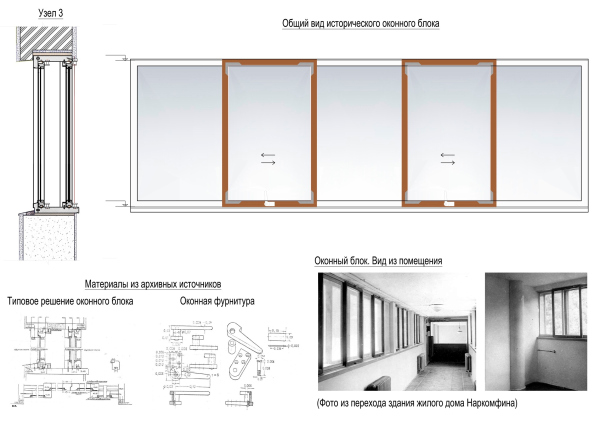

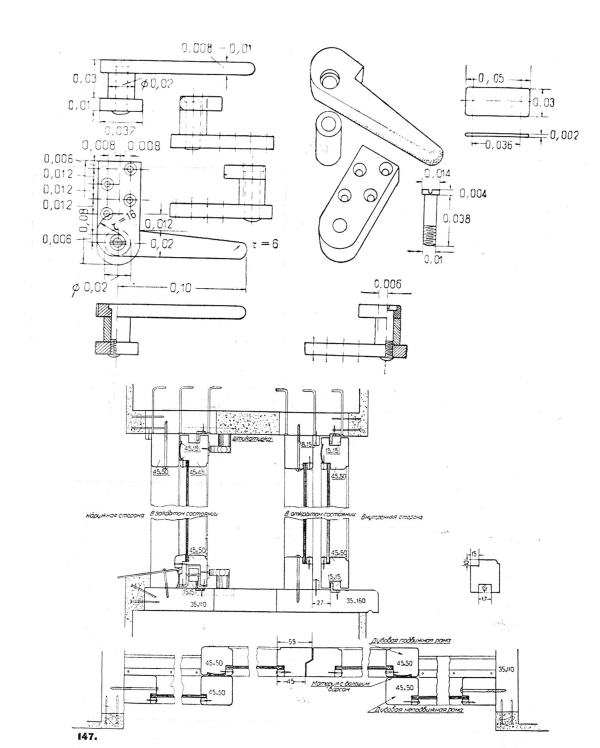

Ginzburg Architects finished the restoration of the Narkomfin Building’s laundry unit – one of the most important elements of the famous monument of Soviet avant-garde architecture. The laundry is the closest to the Garden Ring component of the Narkomfin complex, authored by Moisey Ginzburg and Ignatiy Milinis. It is situated behind the Chaliapin’s house, on the frontline of the Novinsky Boulevard; earlier it had an open space in front of it. Currently, however, this place is occupied by the Fyodor Chaliapin monument. In the 1920’s, the laundry unit marked the border of the experimental avant-garde architectural ensemble: behind it, a green public territory began, leading up to the famous “Ship House” standing in the depth of the land site. Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg ArchitectsBefore the Second World War, this unit hosted what was then called “Moscow’s First Mechanized Laundry”, which functioned quite successfully – the first floor had in it a hall of washing and drying machines, the second – the staff’s dormitory. In the “maintenance yard” complex, designed by Ginzburg and Milinis, with its social and day-to-day infrastructure projects moved beyond the apartment walls, the laundry was the only structure to be ever completed. There was also supposed to be a garage for the residents’ cars, and a boiler room. After the war, the building passed into departmental subordination and, acquiring alien functions, was overbuilt with later additions. Facade of the Laundry Block. 1995.Copyright: Provided © Ginzburg ArchitectsFacade of the Laundry Block. 1995.Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg ArchitectsQuite symbolic is the fact that it is this utility unit that took on such “welcoming” role in the Narkomfin Building. It was accentuated by the composition of the whole ensemble: the construction that included placing some of the first floors on supports functioned as some kind of a “checkpoint”, at the same time being a paraphrase of the main building, demonstrating similar techniques. Recreating the volumetric and spatial structure of the 1932 laundry unit, “Ginzburg Architects” returned to the building the “supports” or “legs”, as they were called, which were overbuilt back in the day in order to get more square footage. Freely flowing underneath the supports, the space of the park, organized in two diagonal promenades, flowed further on and ended in a sightseeing platform. The green islet – the remnant of the Chaliapin Estate, is still to be clearly seen on the map of the city. In the Soviet times, during the reconstruction of the Garden Ring, some of the trees from destroyed boulevards were replanted here. Still in the 1920’s, Moisey Ginzburg tried to save as much as possible of the existing greenery, the vegetation being an important part of the complex; in his “Dwelling” book he writes about the Narkomfin Building: “situated in a park”.  The masterplan of the original Narkomfin Building. 1929-1930.Copyright: The Central Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation of Moscow / Provided by Ginzburh Architects Floor plans of the laundry block. 1929-1930.Copyright: The Central Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation of Moscow / Provided by Ginzburh Architects Masterplan of the Narkomfin ComplexCopyright: The Central Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation of Moscow / Provided by Ginzburh Architects “The maintenance block of the Narkomfin Building”Copyright: The Central Archive of Scientific and Technical Documentation of Moscow / Provided by Ginzburh ArchitectsBefore the restoration, the laundry was in a ruined state. In addition to clearing off the later layers, “Ginzburg Architects” had to recreate a lot of things from scratch. “The building was left to rot for almost twenty years – water was freely coursing through it, all the utility lines were cut off, and bums lived in there. It was completely abandoned, no one took interest in it, and it frequently changed hands. This is why the task of conservation was a very challenging one – there was very little original material left, which was kept intact and was fit for conservation. And, curiously, one of our tasks during this project was to make sure that the laundry does not become a totally newly-constructed building” – Aleksey Ginzburg shares.  Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects The laubdry building, September 2005. Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg ArchitectsA very important step on the path of getting the building back to its original condition became the “clearing off” the outside staircase of the later-added glazing, where the restoration experts were able to preserve some of the stair finish. Originally, the stairway led to the second floor with the staff’s dormitory. The restoration team also carefully preserved a fragment of the historical stucco of the west facade, which gave the idea of the its coloristic solution. It was uniform for the whole Narkomfin architectural ensemble: the buildings had textured white stuccoed walls, combined with round black columns and smooth gray ribbon windows.  Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg ArchitectsThe fragments of the authentic texture inside were turned into “bodies of evidence”: the best preserved fragment of the thatch-board, for example, was integrated into the interior as an exhibit placed under glass. Some of the historical brickwork was also left intact as the historical material. The architects also saved fragments of the air shafts that they found in the course of excavation.  Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects“Sadly, the original decoration of the interiors did not survive. We only found the remains of xylolite (sawdust cement) as the floor coverage on the second floor, and the multilayered paint in the walls. Currently, we have recreated the wall finish with paint over stucco. The western wall has a bluish tone because this is the only original color that we could find in the course of our technological survey” – comments the chief architect of the project, Maria Kuzina. The west and the north facades. Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg ArchitectsEngineering and construction-wise, the laundry, just as the entire house, was an experimental project. Characteristic features of the construction were standardization and pre-manufacturing of some of the elements. The basis of the building is constituted by a reinforced concrete framework filled by brickwork of two types. For the outside walls, which also functioned as the heat insulators, they used hollow-bodies slag-concrete blocks of the “peasant” type, filled in between with fine slag. For the internal bearing walls, masonry of hollow stones with one row of voids, the so-called hard stones of the engineer Prokhorov system, was used. The system of utility lines was positioned vertically and horizontally in the hollows of the brickwork of the bearing walls and intermediate floors. “As far as the restoration work on the laundry goes, we performed it in accordance with the original technology – Aleksey Ginzburg says – We researched the possibilities provided by today’s construction materials, which at the same time match the original materials in terms of their performance. For example, we found the concrete blocks very similar to “peasant” blocks, and when we were laying them, we used the laying method very similar to the original one. We also used the original project to recreate the slabs cast over precast joists, and the system of sliding windows. All of this was important for us because we wanted to make sure that we have the right to say that the new parts of this building have been recreated in full accordance with the original technologies and the original design ideas.” Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright © Ginzburg ArchitectsFor example, during the restoration of the brickwork fills in the outside walls the architects found lightweight expanded clay aggregate blocks of similar sizes; for restoring the floor slab, they used slabs cast over precast joists, similar to those that were developed for the construction of the Narkomfin Building. Among other things, the architects restored the lost fills of the door and window apertures with the metalwork. The original ribbon windows were one of the Narkomfin inventions – they consisted of reinforced concrete frames and moving parts of oak, sliding on a roller. “We restored the window blocks completely true to their historical drafts – the size, the system of moving frames, and the color design solution, for the sole exception that the concrete frames were replaced with wooden ones, and there were insulated glass units installed on the inner thread” – Maria Kuzina says. Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg ArchitectsWhat also changed was the “roofing pie”: the architects restored the historical folding roof covering with a 7-degree tilt. With a view of using the roof in the summertime, the project provides for a quick-mount boardwalk on adjustable legs, along with an outer staircase that also functions as an emergency staircase for the second floor.  Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Fragment of the archive drafts. Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: Photograph © Ginzburg Architects Project of restoring and readjusting the architectural heritage site “Narkomfin Laundry”Copyright: © Ginzburg Architects“As such, the laundry is a fine specimen of constructivist architecture, and at least because of that it had to be restored – Alexey Ginzburg emphasizes – We, however, also attached a compositional meaning to restoring this building because it is an important part of the environment that we wanted to capture and show in a conservation mode as the idea of our avant-garde architects of the 1920’s together with the public space.” Currently, the laundry unit and the main buildings have different owners. According to Aleksey Ginzburg, the perfect solution would be to indeed turn the restored unit into a laundromat as a social infrastructure project for the residents of the nearby houses. The owner, however, did not warm up to this idea. A more likely scenario is turning the building into a city cafe. In a word, the “laundry” or the “maintenance unit”, seemingly purely functional and insignificant, turns out to be a very important element of the complex, even the key one in some sense. The main idea of the experiment, which was conducted back in the day by the Stroikom section in the Narkomfin Building, just as in a few other houses, built in other cities, was changing public life, making it not so much “commune” as “communal” – this term is different from “commune” because it is more about comfort, and because it essentially became the predecessor of the experiments of the XX century, facilitating people’s lives and capable of channeling the energy that we spend every day on doing routine tasks into creative activities. In the Soviet model, the experiment, not being substantiated by anything, in spite of a series of attempts, probably failed – yet it rather was successful on a global scale, and let us not forget that the Soviet avant-garde architects took an active part in it. In addition to its town planning significance of “propylaea of the Narkomfin Park”, an entrance building of sorts, the laundry building was part of the life-changing project, done by the architects of the group headed by Moisey Ginzburg – and, unlike the cafeteria, which is known to everyone, the most forgotten part of it. The completed restoration project returned to the construction front of the Garden Ring an element which was hitherto overlooked by public attention, while the architectural ensemble became more complete and got another little share of historical justice. It is a quite a pleasant surprise how this complex, which stood ready to collapse and dissolve in the ground, many times bewailed, could completely restore itself in some four or five years. Even though, as we remember, it took 30 years of frantic efforts to make this ultimately happen. The project of restoring the Narkomfin maintenance building brought Ginzburg Architects the “”. |

|