|

Erik van Egeraat is one of participants of an exposition of Russian pavilion of XI Venetian architectural biennial

I remember how you congratulated Dominique Perrault on his victory in the competition to design the Mariinsky Theatre. It happened in the bar of the Hotel Astoria; I was sitting nearby at the time. Would you congratulate him today?

Really? I no longer remember. But, of course, there are now fewer reasons to congratulate him. Many people are talking about what happened, but no one knows for sure. And I can only roughly imagine what was the problem. Yes, it’s a very sad story.

Is it easy for foreign architects to work in Russia?

Well, in any case, it is possible to do so. And all the more so in today’s Russia, a country with an amazing range of possibilities. If you compare Russia with England, where I also worked for a long time, I would prefer Russia in many respects.

In which, for example?

English architecture is excessively formalized. The rules are absolutely rigid. If you want to create Avant-garde works in England, you first have to get permission to do so. You’ll never be admitted to the cultural elite on equal terms. Unlike in Russia, which is much more democratic and liberal. Even if there are some particular aspects of Russian life that take getting used to.

What about modern Russian architecture?

For the most part, it’s not bad. Of course, when it comes to what’s built by the developers, Russian architecture could be more cultured, less vulgar than it sometimes seems when seen from a slight distance.

How long have you been observing it ‘from a slight distance’?

I have been visiting Russia from way back, and I’ve lived in Moscow. In 2000 I found Capital Group, the first partner in Russia with which I was able to work.

How did your collaboration begin?

I had an acquaintance, a young Russian architect, who worked for Capital Group. We met, and as a result they offered me a job as their architect. But since I had worked for myself for 20 years under my own name, I made a counter proposal: that I should remain an independent architect, but would work closely with and for them. It’s how I usually work with my other clients. We worked together very successfully for a certain time, and then we went our separate ways. But you know the story of how that happened.

Tell us about it in more detail, though, if you don’t mind.

The situation with Capital Group was quite simple. I came to Russia because I intended to work with them. I set up an office, we created an unusual design, and we managed to get it talked about. This continued from 2000 to 2004, when it became clear to me that they were in fact intending to build something else – not what I had designed. I could have agreed to certain changes that would have allowed the project to remain within the bounds of the logic I had devised, but the changes they made were unacceptable to me. From this moment relations between us soured and we stopped working together. I could never agree to my City of Capitals project being changed beyond recognition without my even being asked.

Has anything changed since you won your case against them in the Stockholm Arbitration Court?

No, their position has not changed in the least. They still think they own the copyright. They’ve even said I was attacking Russia, although I was fighting not against Russia, but for my own rights.

And at the same time people from the American firm NBBJ, which completed the project, have come to me to apologize. They say there was a misunderstanding and they realize they were in the wrong.

Perhaps it’s easier in Russia to work with state clients rather than private ones?

As in any country with a large state machine, your bureaucracy turns slowly. It has so many different levels and even when you have the approval of the mayor, the prime minister, or even of the president, this is no guarantee that you’ll be allowed to get on quietly with your work. Everything depends on the client himself. I have a project in St Petersburg that is smaller than City of Capitals, and it’s progressing much better. My client there makes much more of an effort when it comes to organizing the work and the quality of construction.

How much does it worry you when your name is used simply in order to increase the sales potential of a project?

It’s not just with me that this happens. This is a problem that involves the entire world and the entire architectural community. It goes back to the early 1980s. And here it’s senseless to curse the greed of developers or architects’ megalomania or folly – or mine, for that matter. It would make more sense to blame the state, whose responsibility it is. You have to understand that when such enormous money is drawn into the game, without any correction being made, without any control by the state, there are bound to be excesses. You need restrictions, state regulation.

But as a Dutchman – and therefore a born democrat – you should find the idea of speculation in architecture repulsive.

But what do you mean by ‘speculation’? Incidentally, Dutch society is not so open and transparent as it makes itself out to be. It is a small society, but it contains as much unfairness as any other. In any case, more than it desires to see. But you are right in that young people in Holland are always protesting against speculation involving real estate. And while young people protest, the developers are hard at work. Even in Holland, my native country, it’s possible to build a house in the centre of Amsterdam that, even before it is completed, sells for several times more than it cost to build. 100% profit. If this is possible in Holland, then just imagine what kind of profit can be made in Russia. This is more money than you could possibly turn down.

Is there a difference between architects’ intellectual-property rights in Russia and Europe?

To take care of his rights, an architect should have a contract with the client; and this in itself implies that since the client agrees to sign a contract, he will build the design – and precisely this design and not something resembling it. So I never rush into agreeing with a client until we have settled everything on paper. In Great Britain the situation is a little different. There you have to come to a special agreement about this.

Is it conceivable that in Europe you could have a situation whereby Perrault’s Mariinsky Theatre was being built without Perrault?

It’s for the architect to fight to have his design realized in an undistorted form. And if Perrault has nothing against those who are realizing his project, then there’s no problem.

How painful for you was it to see Russian Avantgarde, the street block you had designed, moved to another site? There is a story that there was a meeting at which Luzhkov said the project was fine, but not for the location for which you created it.

This was the summer of 2004 and the management of Capital Group was very upset. As for me, I could admit that there were reasons for Luzhkov’s decision. For instance, the site originally proposed was too close to a small church. I asked the authorities to move the project to another site, but to find this site near the Central House of Artists.

What is currently happening with Russian Avant-garde?

There are still plans to build it, it seems. But this is one of the most difficult designs to build even in my experience. I do not know whether my client is prepared to realize it. It is a very large and ambitious project.

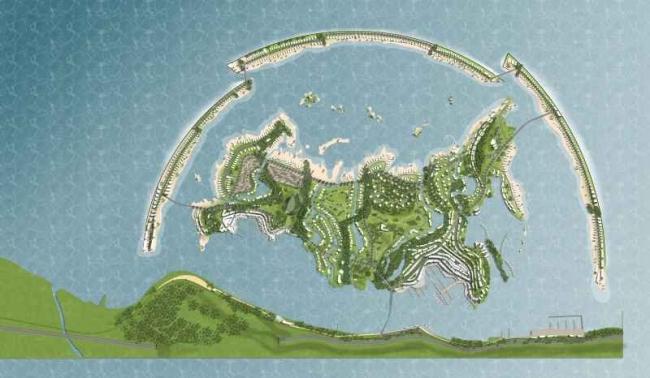

As ambitious as your project for an artificial island reproducing the contours of Russia in the sea off the coast of Sochi? The latter project is slightly Arabian, slightly American, and, of course, Dutch in that it involves the creation of new land in the middle of the sea.

Yes, it slightly resembles the currently fashionable projects being realized in the Persian Gulf and America. Such are the fruits of globalization. It’s the done thing to rail against globalization, to say that it leads to loss of national identity and so on, that it allows money to decide everything. But if you look at the history of architecture, you will see that the crossing of state borders and exchange of ideas has been an excellent way to develop national cultures. The best Baroque architecture in Poland was created by a Dutch architect. We have no Baroque in Holland. We were not so passionate in our love of God as to build such lavish churches to Him. I find it fascinating to introduce this kind of international gloss into a setting as interesting as Sochi. Here Russia, the Caucasus, Europe, and Asia meet. It is the crossroads of the world, just like the larger version of Russia.

How accurate is your copy of the ‘larger version’? What does your island have where Moscow and the Siberian prisons should be?

When it comes to such details, the model is, of course, not accurate. This is not a geographical map. Otherwise, I would have to reproduce your beautiful rivers, every bend that they make, all your hills and plains. But this is not a copy of Russia. I remember a film called Toy Trains. It began with an announcer saying, “This is a film about toy trains. Toy trains are not miniature copies of trains.” They look like trains, but we use them for playing with. For fantasisizing. This is a toy, a metaphor for a train, and not a model.

You have created a metaphor for modern Russia – perhaps a metaphor for how Russia would like to see itself: small, well looked-after, in the middle of a warm sea in which all its neighbours have conveniently drowned.

Russia stands every chance of becoming a very attractive country. Both the large version and this small one. It may not be 100% right, not 100% accurate. Like all good things that exist, it cannot be completely regulated. It’s a little dishonest, too expensive in places, too cheap in others. There is no artist in the world who could say, “My art is absolutely truthful.” Everyone embroiders a little.

When you are asked what you’re designing or building at the current moment, you usually reply that you’re working on something but it’s too early to speak about it.

It’s not that I’m suspicious of everyone. I simply try to be careful. I learnt my lesson with Capital Group, when I worked with seven designs and some of them were built – only not under my supervision. Currently, there are 17-18 projects on which I’m working in Russia. This evening, I shall present a project to my client from Siberia. We hope to start building by the end of the summer. In Moscow I have four projects, construction of one of which should begin in the middle of year and one of which is currently under construction. Closer to completion, it’ll be possible to speak about it.

Is there a fundamental difference in the way that Russian and Western architects work?

Russian architects are changing fast at the moment. There’s less difference between young Russian and foreign architects than between Russian architects from different generations. Currently, I have several young Russian architects working for me, and I’m very satisfied with them.

Could you define the different schools of architecture in relation to architecture as it is practised here in Russia?

Well, Swiss architects, for instance, have gained their reputation because they are used to providing an extraordinarily detailed project for not just a particular building, but its entire surroundings as well. Such are the requirements in Switzerland. But Swiss architects are, in the context of Russia, too demanding of both themselves and others. The Germans are excellent architects, but a little dull. And the French style of architectural behaviour is likewise not suited to Russia. American architecture is, like the Americans themselves, heavy, large, and noisy. American architects are very energetic and good-natured, but not always elegant and precise. Russian architects perhaps resemble Americans. They are reaping the fruit of the construction boom. They are designing buildings in large numbers, but, on the other hand, they are not very good at monitoring what they are building. They are in a hurry to do as much as they can. Many, I would say, have been spoiled by the current situation.

I am relatively optimistic, but would like Russian architecture to be more European and less American or Asian. Otherwise, they’ll turn Russia into Dubai. I don’t know whether the inhabitants of Moscow will be glad if they wake up one day to see that their city has become as modern and as ugly as Dubai.

Do you think this process can be halted?

When I look around me, I see some buildings that I like, but others that are just indescribable. When I spoke to Luzhkov, he asked me why I wanted to build such complex buildings. I replied, “Look at the room where we are now. It is richly decorated, rather than simply painted with stain-resistant paint. We are talking of important things. You are an important person and Moscow is an extremely important European city. The interior design of your office emphasizes this thought – through its décor. I want to do the same with Moscow – through my buildings. If you have a large building, it should be rich in design; it should be complex, so that it appeals to people rather than shocks them.” And in the end Luzhkov said, “Very well. Go ahead.” And still they designed those buildings the wrong way. I fought all I could, but the buildings at Moscow City – there they are, outside this window, in the panorama of Moscow. You must abandon the American path of development. Russia is too beautiful for you to take this path. I feel a connection to this country. I have a Russian wife; my son is half Russian. I’ve been here for the last 18 years and Russia has given me enormous opportunities. There are, unfortunately, some downsides, but, then, which country does not have its downsides? I am very happy here.

Many foreign architects complain that it’s difficult to work in Russia.

That’s strange. Why come to work in a country if you’re only going to complain about it? Yes, I can see a future in Russia. To be honest, I am not worried about how everything is going to develop – whether things will get better or worse. I am very happy in Russia because I see changes for the better, and I am a part of them myself – I do what I can. I am ready to wait, I’m ready to make concessions to my clients and not lean on them. And now I remember what it was I said to Dominique Perrault in the bar of the Astoria.

And what was that?

I said, “Congratulations.” Although I was not glad, of course, that it was he who had won instead of me. “Congratulations! If you can build this building. If you feel you have the strength to build it.”

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

|