|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 01.09.2008 | |

|

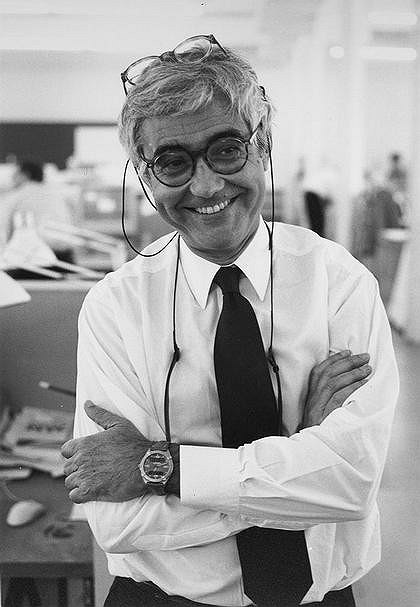

Rafael Vinoly. Interview by Vladimir Belogolovsky |

|

|

Vladimir Belogolovsky |

|

| Architect: | |

| Rafael Viñoly | |

|

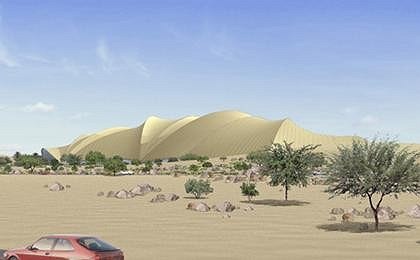

Rafael Vinoly is one of the the participants of the exposition of Russian pavilion of XI Venetian biennial of architecture Rafael Viñoly Architects is a leading international practice with over 250 design professionals in New York, London and Los Angeles and in site offices around the world. The firm’s widely published projects include The Kimmel Center for Performing Arts in Philadelphia, Jazz Theater at Lincoln Center in New York, the Gabrielle H. Reem and Herbert J. Kayden Center for Science and Computation at Bard College in Upstate New York and Van Andel Institute in Michigan. In 1989, the firm’s Tokyo International Forum design was selected out of 395 entries from 50 countries. This stunning civic complex was completed in 1996. An enormous glass enclosure with a dramatic 750-foot-long truss is supported on two elegant columns so distant from each other that the entire structure seems to be floating.. The architect was born in Montevideo, Uruguay in 1944 and, at the age of five, moved to Buenos Aires with his parents a math teacher mother and a theater director and producer father. At the age of twenty, while still a student Viñoly became a founding partner of Estudio de Arquitectura in Buenos Aires that soon became one of the most productive and successful firms in South America. In 1979, he left Argentina, by then a military dictatorship, and emigrated to the US with his wife Diana, an interior designer and their three sons. After teaching at Harvard and working as a developer, he opened his architecture practice in 1983 in New York. Currently, Viñoly is designing several residential towers at Park-City development in Moscow. Our conversation took place at the architect’s three-story studio in SoHo. It features the grandest single room where architects work in New York, while the basement-level model shop engages the pedestrians in the process of architecture- making. We sat down in Viñoly’s spacious private office at a large round table near two black Steinway grand pianos. While responding to one of my questions, the architect drew an outline of a five-pointed star with a sickle around it and concluded, referring to the Soviet constructivists: “These people invented everything. It was a fantastic moment. If only they had more time, their architecture would transform the world.” Based on the length of time it took for us to set up this interview you must be the world’s busiest architect. What are some of the most interesting projects that you have been working on these days? We are very busy with a lot of work all over the globe. Among the most exciting projects is a new office tower in the center of London, Curve, a theater in Leicester, England, a mixed-use development in United Arab Emirates, the New Terminal at Carrasco International Airport in Montevideo and a major expansion at the Cleveland Museum of Art. You travel a lot. What are the most exciting parts of the world where the process of urban growth is felt the most? Clearly the urban experiment in the Persian Gulf countries is really an absolutely remarkable phenomenon. The concentration of power and wealth is almost equivalent to the time of the greatest empires in history. It is kind of what happened in St. Petersburg in the eighteen century when Peter the Great decided to build a new city in the swamps. So the right questions to ask are – what is the level of responsibility and what kind of policies and ideas are injected into these grand visions? I am particularly speaking of the Gulf countries, because they all have a common denominator, a desert, which is something like tabula rasa. Are you talking about the phenomenon of the instant cities? Well, I think a notion of an instant and completely consolidated city is a very confused idea. The natural growth of a city is a cultural and a very slow phenomenon, and you can’t enforce it. But the culture now has a cycle of 60 seconds or so. It used to take 150 years to build a city, then 50, and now it is only 30, and it will tend to compress even more. What makes many of these so-called instant cities possible is the single source of funding and the power structure, which really mandates their permanence. On the other hand, in a democratic environment – and it is not that I am for it – any new development is a piecemeal operation. It has a much slower and natural growth rate, and a notion of an instant city is much more dubious. I think the idea of instant cities could be great only if they could die as fast as they are built. And that is what technology doesn’t provide yet. But it would be interesting to see a city inflated, used for ten years and when no longer needed – disassembled, packed and shipped somewhere else. Let’s talk about your housing project in Moscow and how you got the opportunity to work there. Our site is a part of a much larger master plan Park-City project designed by KPF. They recommended us to the local developer, and that is how we got this project. We were given a very interesting site along Moscow River with the idea to build five residential buildings. We are working on three, and a Beirut architect, What is the idea behind your design? Any relation to habitable bridges in the sky similar to the ones you did in the ‘70s in Buenos Aires? Unfortunately, we were not able to do a lot of experimentation, because the building envelopes were preconditioned and given to us by KPF. They are the ones who interact with the client, and all the approvals go through them. The idea by KPF was that five buildings of different heights would gradually rise from short to tall towards the Ukraine Hotel, one of the seven sisters’ historical skyscrapers in Moscow. These buildings are circular in plan and provide many more views than in typical orthogonal organization. However, these towers are not proportioned with perfect one-tonine slenderness ratio, so they are a little chubby and not extremely exciting. How would you describe your relationship with the client? Well, I am not directly in contact with the client. Formally, we work for the Park-City development group and we interact with their people, but most of the contacts are done through KPF. About six months ago, I presented our scheme before a large group of investors in a wild night club in Moscow, and the lights were so bright that I couldn’t quite see who I was presenting to. Usually when I work on projects, I enjoy the bureaucratic side of architecture very much – meeting with city officials, presenting to the public and so on. In Russia, it didn’t happen. I agreed to this type of arrangement just to have a chance to work in Russia and to engage in the culture, which I know very well. When I lived in Argentina, I was surrounded by Russian culture, and, as a teenager, I accompanied my father on a couple of trips to Russia. I knew a great photographer who was a Russian immigrant. He was a very close friend of my parents. I even studied the language, and I still remember a few things. For me, architecture and engagement in culture is the same thing. Russia has a very rich cultural tradition and very strong understanding about how cities should be developed. Did you have a chance to see Moscow during your recent trips? I know the city mainly through publications. I know what Norman (Foster) is doing, which is enormous and probably not his best work. In the last year, I went there five or six times to see the site and to meet the project team. I have mostly been to the key landmarks and mostly at night after the meetings. But I think I have a very good smell for it. I can imagine it very well. Do you get a sense that a grand new city is rising in Moscow? I think it is very difficult to erase the traces of architecture, so much of which was built in Soviet times. Although, I must tell you that I was shown one particular building and people told me it was a disaster, but I thought it was great. It was a very regular mega structure, unbelievably long, easily 700 or 800 meters. It looked like geography, not architecture. It is scary! Unfortunately, I didn’t visit any constructivist projects. But I know them well through books. Also, you might remember a few years ago, there was a spectacular constructivist show in Paris. It is a major influence on so many architects in the West. If you think about it, most of the imagery of what is considered to be cuttingedge architecture today is based on what was done then. It was very fundamental period. Not only as far as new forms, but mainly through inventing socially engaging architecture, a fantastic moment. Do you think it makes sense for foreign architects to build in Russia? I don’t know if it makes sense or not. I think the problem is not whether the architects foreign or not, but whether they are good architects. A good architect could work anywhere because a good architect does not come to the new place with a proposal that he did before. Nowadays, there is this stylistic branding and an enormous amount of superficiality in architecture, which you don’t need in Russia. What project do you consider as defining for you personally? I think the Argentina Color Television Center in Buenos Aires. I was in my early thirties and in control of everything. The building process was so unique. We started construction without really knowing what we were doing, and that is teaching you a great deal. How do you start construction without proper working drawings? Well, you put the grid on the site and just do it. We built the project the way I think all buildings should be made – as sort of improvisation on a set of working drawings. We just went to the site and said to the contractor: “Do it from here to there.” We improvised so much, and that is what gave the building its freshness. Tokyo Forum was exactly the opposite. The challenge was to produce the project in a highly descriptive, precise controlled environment. Did the idea for Tokyo International Forum really come from Pan Am logo? Yes. I had quit the project because I couldn’t come up with any good idea and I went to Paris to take a break on a Pan Am flight. And when they started serving dinner, I saw this logotype on my napkin, which were these ellipses inscribed in a circle. What was incredibly difficult at that time is that I couldn’t understand how to reconcile the curving of the rail tracks and a very rigid geometry of the octagonal streets adjacent to the site. So when I saw that logo everything just fell into place so perfectly. Yes, it was just like that. I landed in Paris and took the plane back to finish the project. You know, nowadays the architects claim that they no longer have these singular visions that just come and enlighten them. They say it is all about team efforts and from early on, all the consultants gather and they develop projects collectively because architecture is so complex that one person could not possibly do it all. Yes. I heard about that. You heard about that. So how does it work here? It doesn’t work like that here and not because I am opposed to this idea of collaboration but because I am against projects that are results of mini contributions. Architecture, at the end of the day and despite of what people tell you is a compositional business. It is like jazz. If you ever played jazz it is incredibly free, but it has much more rigidity than people tend to realize. By rigidity, I mean it has structure. It has moments of freedom. But you need to have some form of cohesive composition behind it. And you can only have it if you understand how complicated buildings are. If you think architecture is pictorial only, then you miss 90 percent of what it is about. If you are firmly grounded in constructability and in the knowledge of the systems, and if you have the capacity to go quickly back and forth, then you are really capable of having control over the whole thing. I know how people work, and even if they have this kind of everybody contributing things, at the end somebody puts everything together. Tell me if I am wrong, but you have a reputation of having this amazing capacity of being a one-man show. Is it true? No, it is not true. How can that be? It is absolutely not true! What I mean is that you tend to design and work out the entire project to the very minute detail on your own, without relying on intellectual support from your staff. Well, it is a pluralistic and collective practice out of shear complexity of architecture. It is ridiculous to think that I do everything, and I don’t claim that. But I want to make one thing clear – I don’t believe in a practice with multiple designers. I have chosen not to practice that way, because in my own terms, it is kind of unethical. If you sell a product designed by people who are no longer around, then you are building on top of their talent and not yours. So if I were the client, I would want to see what the person does and not the company. That is the problem with corporate offices. As far as design, how much of what your office does is really you? Well, as far as design, I have a very tight control on everything that comes out of my office. How do you work? A couple of days ago, I was looking at a book with pictures showing Eero Saarinen working on his models. They were taken by a model maker, and you can see this man engaged in the process of working out design problems through large-scale study models. This is something that I learned from Cesar Pelli, and Pelli and Saarinen learned from Louis Kahn. That is a fantastic tool. And that is something that makes a designer an architect. So I don’t believe in sitting down with brilliant people who tell me something and I am then supposed to come up with something that fits their parameters. I draw it, and then I work it out in models. Do you care about what is going to happen to your practice when you are no longer around? I do care. But to be perfectly frank, it is something for other people to figure out. Are you preparing a new generation of architects? Absolutely. We have a fantastic team of people here. Do you ever delegate them to do a project from the start? Never. No. And how many projects do you currently have? Forty-four projects in nine countries around the world, which we do out of three offices. Well, let’s talk about music. Your first career began as a piano player. Is it still a big part of your life? Oh, yes. You can see it here. How many grand pianos do you own? Nine or ten. Some of them I lent to people. My son has one. My brother-in-law has another one. You built a Piano Pavilion on Long Island. What is it like? For me, it is a refuge. It gives me a great comfort and this place is not about any visual effects. It is about how you feel in the space. You mentioned Louis Kahn. He is a great influence on your work, right? If you want to see great architecture, you must go to Fort Worth to see his Kimbell Art Museum. We all have seen it. We have pictures of it. We know it through models and everything, but when you come into this place, the experience has nothing to do with what you see. It is about what you feel, and that is what makes great architecture – the subtleties. You studied both music and architecture. Do you think there is a particular link between these disciplines? None. Zero. It is totally something else. The only thing that they have in common is this inevitability of compositional mission and experiencing a sequence of events by going from one moment to the next. In that regard, music and architecture are the same thing. Your office runs a special research grant program. What is it about? We started the program three years ago. The objective is to encourage working architects to come up with new approaches to design. In the beginning, we had one researcher each year and this year we will have five. There is a lot of theoretical discussion in architecture school and less about how you go about designing a building. The program has already produced some new approaches to design. For example, two years ago, Joseph Hagerman who won this opportunity to do a research in our office designed a green roof where vegetation can grow. Now, we have plans to use this idea on one of our projects, a green roof on a high school in the Bronx. I also teach a course within our office. We form a group of about 20 to 25 people from the office and outside. I teach about how the profession works. We meet once a week for thirteen weeks in the fall. Passing along this collective knowledge about architecture can only make the profession better. I think teaching in architecture needs to focus more on the craft rather than nurturing a talent, which is something that is very hard to define. The best thing is to learn by being in the office and observing how the other person works. There is a lot to learn about architecture. And it is not just about whether you are good with your pencil. Architecture, as any other practice has instruments and techniques. In that sense, it is like music. You can’t just talk about it. You have to perform. What advice would you give to young architects? Work. Work a lot. Try to be near someone who knows the process of architecturemaking. I think what is absolutely critical in architecture is that it is about composing, and you can not subcontract that. It is a question of using the proper tools and understanding how to relate them and understanding the complexity of the process. I think these things can be taught and need to be learned. You don’t just inherit it. What qualities or sensations do you want people to notice in your architecture? What messages do you try to convey? The first thing that makes a good building is a challenge of a building type, which is transformative. I do believe in evolution. If you did a house one way, there must be another way of doing it better. And secondly, it always comes back to one single aesthetic phenomenon, which is the control over proportions. And I don’t think it is inherited in people. This is something that you can learn through building and certainly not just drawing. That is the capacity that if you get it right you feel extraordinarily secure. In fact, you may make people feel happy just with that. This dimension is timeless, and whether you go to the pyramids or the Kimbell Museum you feel it. Rafael Viñoly Architects office in New York  None None None None None None None None None None None None |

|