|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 23.12.2019 | |

|

The Terraces of the Crystal Cape |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Nikita Yavein | |

| Anton Yar-Scriabin | |

| Studio: | |

| Company: | |

|

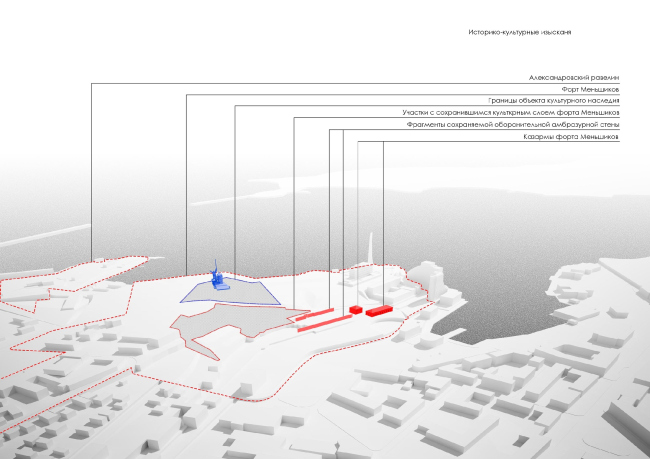

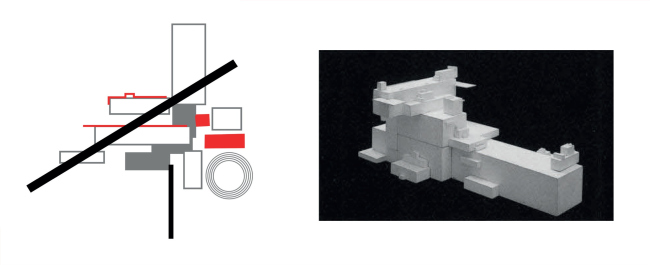

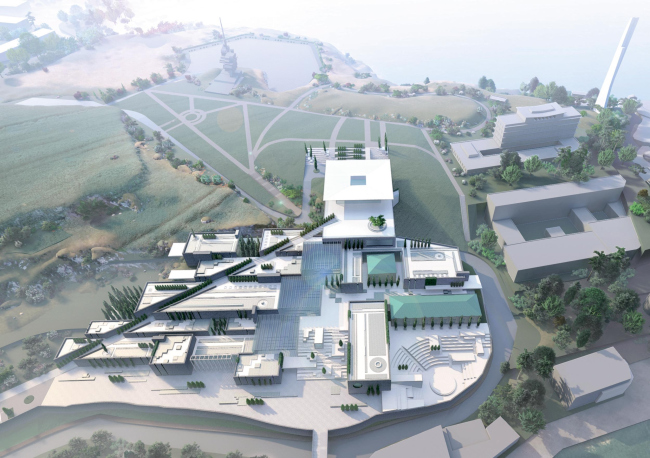

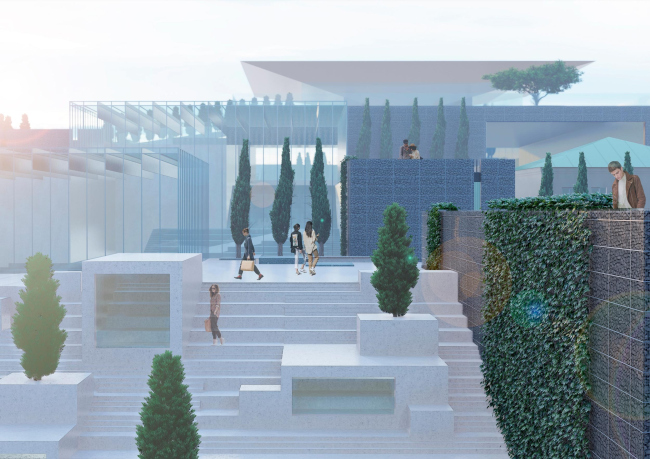

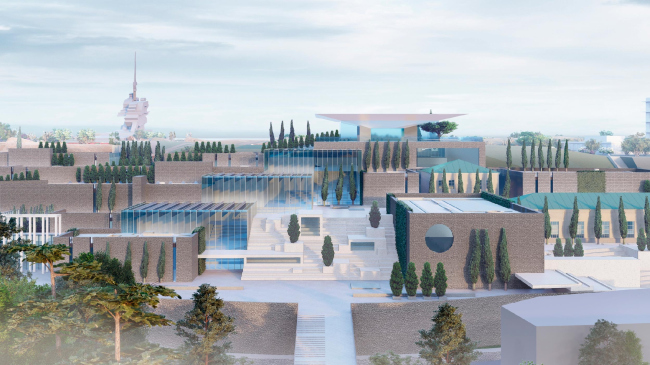

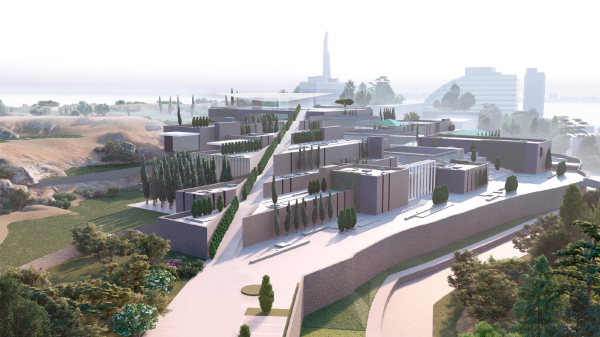

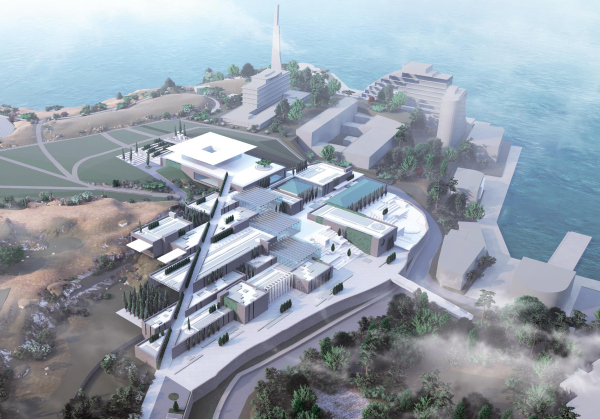

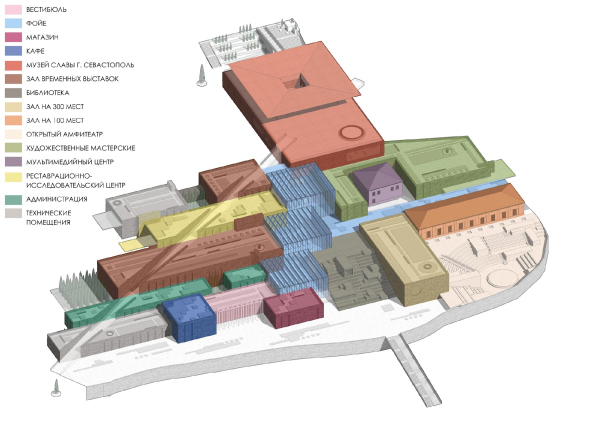

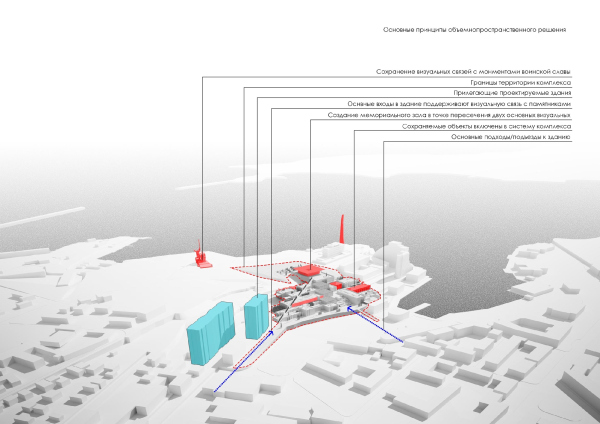

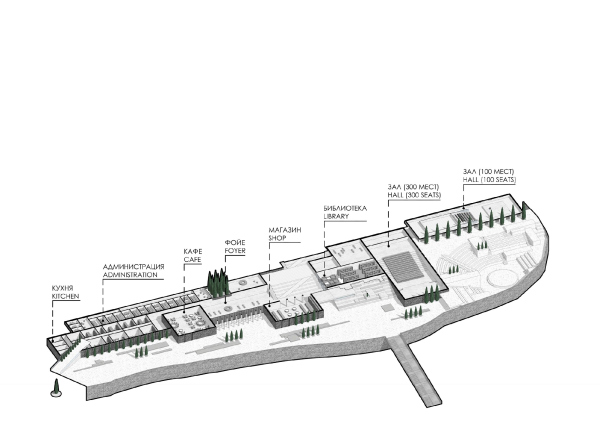

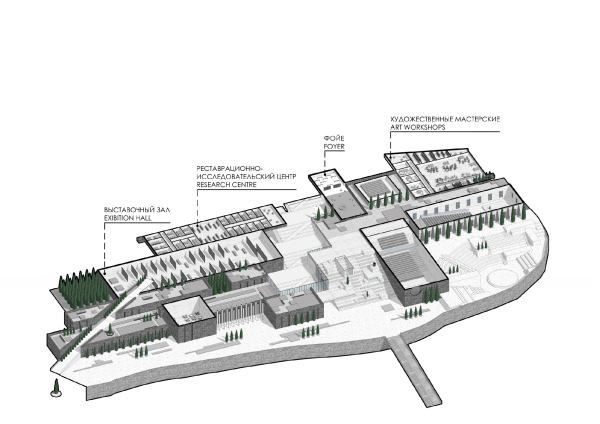

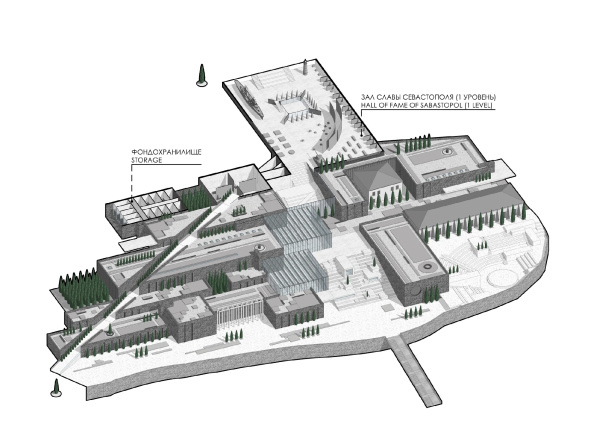

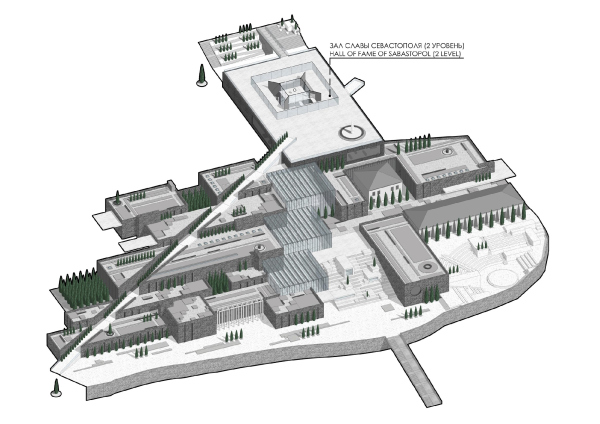

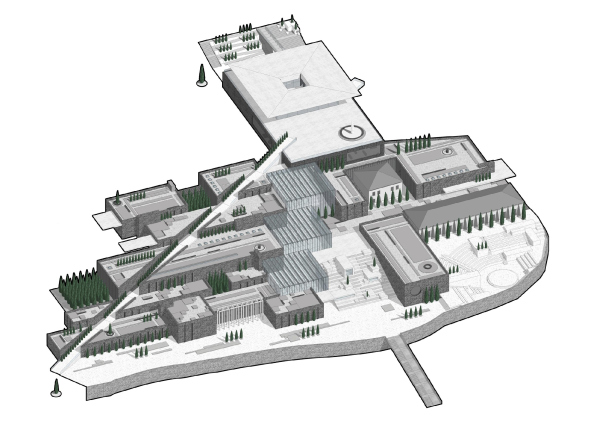

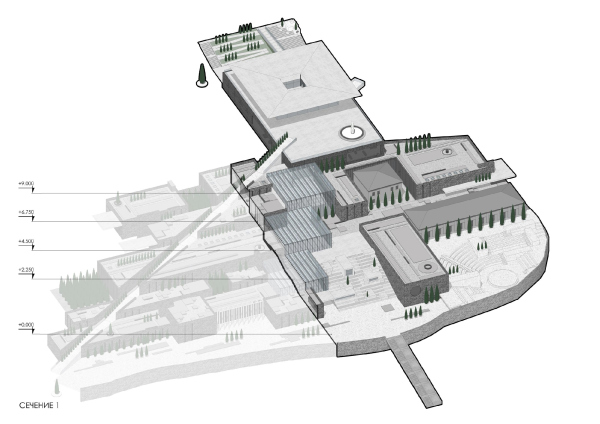

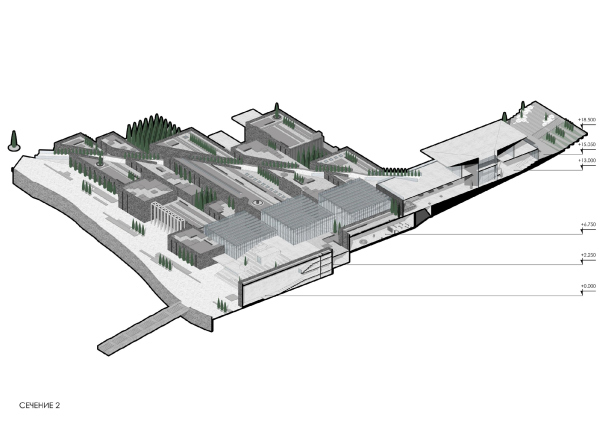

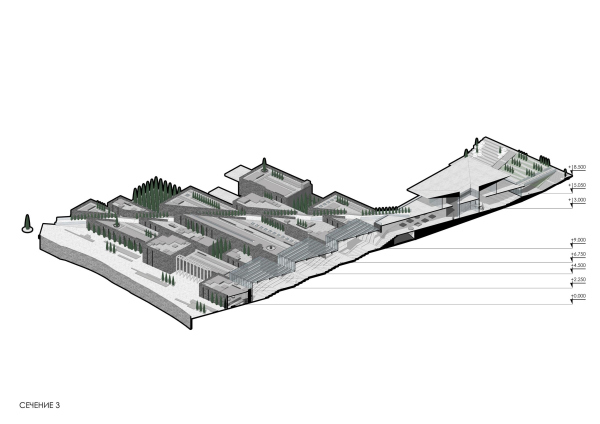

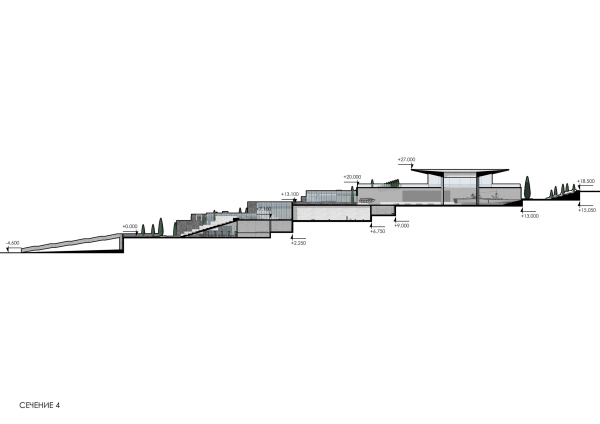

Proposed by Nikita Yavein, the concept of a museum, educational, and memorial complex to be built in the city of Sevastopol avoids straightforward accents and over-the-top dramatics, interpreting the history of this place along with the specifics of its landscape, and joining the public space of the operated stairway and amphitheaters with an imposing monument. The memorial complex to the defenders of Sevastopol from the Nazi siege of 1941-1942 on the Crystal Cape was conceived as far back as in the early 1970’s; the history of its implementation was about forty years long; the city got back to the concept in the mid 2000’s, yet all they could do was build two Soviet monuments: “Bayonet and Sail”, commemorating the awarding of Sevastopol with the status of “hero city” (1977) and “Soldier and Sailor” (1971-2007). Then they started designing the buildings of the complex, and even the foundations were laid, but the project never was completed. The new design period started in 2017 – in the exact same spot, on the territory of the former Munition Factory 54, the city decided to build first, in addition to the memorial complex, an opera and ballet theater: for a while, a project by Coop Himmelb(l)au was widely discussed, yet Wolf Prix publicly announced that he would not do this project in the early 2019. Right about that time, the foundation “National Cultural Legacy” ordered another two projects, yet not of the opera and ballet complex, but rather museum-type, consisting of two parts: the memorial of Glory of Sevastopol (to be built west of the “Soldier and Sailor” sculpture), and a museum/educational complex (to be built on a large land plot lying south, behind the Kapitanskaya Street). Still later on, in the summer of 2019, yet another project came about, then the lineup of construction companies changed, and now the plans for the future development of this area are more than uncertain (unlike two similar museum/educational complexes of federal importance in Kaliningrad and Vladivostok). It is still a mystery how the situation with the Sevastopol complex will unfold.  Carlo Bossoli. Sevastopol. Vew from the north side of the city. The 1850′s. The opening slide of the projectCopyright: public domainSuch an approach endows the project of the museum building with lyrical delicacy, which presents a sharp contrast with the recently adopted vector of the “natural” development of the Artillery Bay, where obelisks and monuments freely alternate with Turkish hotels (vivid examples of the latter are the housing complexes “Cristal Beach” and “Mys Khrustalny”, situated directly on the sea shore). What Nikita Yavein’s project did was turn this extensive trend at a 90 degree angle, towards the search of town planning identity – which would probably be quite a good thing. Some of the terraces already exist on the territory because it is situated on a hill with a height drop of about 15 meters, descending to the sea. The architects are keeping the retaining walls, reinforcing them with new ones, as well as adding mega-stairs of laconic volumes not more than two stories high. Each of these volumes performs a function of its own, and this conglomerate not only “looks” but also “works” as an independent town, in which each of the buildings, knit closely together, has its own task and its own size, conditioned both by its function and the surrounding terrain. The operated roofs will carry terraces gardens, meaning, the “town” will also be a park on a hill to a certain extent. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44The likeness to a city, which grows historically and gradually, is meant to be further enhanced by the two historical buildings of the barracks of the Menshikov Fort: originally, the project provided for keeping them intact, just as the remnants of the embrasured wall. Regretfully, during the past year, these buildings got torn down. The historical and cultural surveyCopyright: © Studio 44However, we will remind you at this point that the project only provided for preserving the historical buildings; from the visualizations, one can see that their roofs are hipped, with four sloping surfaces, the roofs of all of the other buildings being flat. The project is also generally connected with the history of the place. This history, of course, is of the warfare kind because from the earliest times the shore of Sevastopol chiefly consisted of fortifications, the remnants of many of which are still to be seen, and, let’s say, it will be a great thing if they survive into the future... Besides the Menshikov Fort, on the other side of the bay, there are the remnants of the Seventh Battery with its stone breastwork, and the arsenal cistern sunken into the ground – the architects are proposing to do archaeological excavations here, then hand over the discovered remnants to the museum, and tie them in with the educational complex, making yet another entrance from the seaside. This way, the museum complex begins to look like a southern seaside town, grown upon the old fortifications, and mastering the remnants of the fieldwork – something akin to the “imputed” plot, a technique that is popular nowadays; and, although the fortifications are by no means medieval – as Nikita Yavein aptly put it, “Sevastopol is a city that has been many times destroyed” – the end image does look like some Greek town on the Venetian bastions in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. Because essentially this is one and the same culture; Sevastopol started its history as a colony of the Ancient Greeks, and the land plot in question even has a fragment of the vineyards of Hersones, even though the center of the antique town is situated pretty far away from here. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44Meanwhile, in spite of all the similarities between the allusions and silhouettes, the architects are not at all trying to create a “waxwork” of an old seaside town. They achieve the desired measure of abstraction not only by using their own artistic vision, not devoid of megalithic collectiveness, but also thanks to the avant-garde theme, which naturally springs from the project task. It is planned (or was it planned? hard to say) that one of the “anchor” operators of the museum complex will be the XX century department of the State Tretyakov Gallery, the one that is on Moscow’s Krymsky Val Street, which contains the Malevich “Black Square” painting and other fine specimens of avant-garde art. Hence, the list of prototypes includes the Malevich’s Architecton, and a composition that interprets the plan of the complex in a distinctly suprematist key. Left: the suprematist composition on the theme of the project. Right: Malevich′s ArchitectonCopyright: © Studio 44The avant-garde becomes a lens or maybe a melting pot that allows us to “digest” all of the Antique, Medieval, Renaissance, and other allusions, bring them to one common denominator and a terminal degree of generalization, without losing – surprisingly – a single theme. Widening the circle of associations, one would want to remember that Corbusier used to justify his flat roofs with, among other things, the aesthetics of a near-east town, looking like a scatter of laconic building blocks from an erector set, the antipode of the pristine and thought-out Renaissance town. The avant-garde artists, just like their predecessors in general, used to draw inspiration from slums, as opposed to the glamorous palaces of the city center, and from the ancient primitive culture; partially because of that, the theme of the city, being molded upon a hill, which can be traced to the V, or maybe even the X century AD, makes such a perfect match for the examples of avant-garde art in general, and Malevich in particular. However, for all its love for the primitive and for the people, the avant-garde art is acutely personal and individual – and this is why its methods allow the artist to not just follow the masses but govern them. Or at least this is what they are meant to be doing. In our specific instance, this is exactly the case. Fine-tuning their tools and prototypes, thoroughly enumerated in the project book, the architects set the measure for: asymmetrical / geometrically predictable, vernacular / regular, antique / modern. All of this is united in the “architecton”, yet it still allows of various interpretations, and causes, come to think of it, a lot of emotion. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44For example, the amphitheater, sunken into the bottom part of the slope, looks here like a totally antique “neo-Greek” solution (not even Roman because it follows the line of the hill, and does not stand on sub-structures). And the next volume of the “hall for 300 seats” is saluting, composition-wise, to the Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis, which the authors also neatly included into the list of analogies, yet the large circular window at once reminds us about a lot of constructivist buildings, i.e. brings us back to avant-garde. Following this method of free analogies, it brings us to the project of reconstructing the power plant in the center of Pskov developed by Studio 44 in 2016; but then again, it must be said that the circular window, something like a conditional sum of Renaissance and avant-garde, is generally one of the favorite stylistic devices of Nikita Yavein’s, he even has one in his studio. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44Before the hall with a circular window, the amphitheater gets rounded, but on the other side, along the Park of the 300th Anniversary of the Russian Fleet, it is continued by yet another one, stretched in a straight line. And, while the first one overlooks the bay, the second one is more focused in the direction of the city center and the Mayakovskogo Street ending here, whose axis, even if with a breakdown, is still pointed at the Vladimirsky Cathedral before the park with a monument to Lenin. In a word, this entrance, the one from the city side, is probably the main one; the amphitheater functions as the grand staircase of the museum, the only difference being that you can recline on it to watch the sunset. The stairs of both amphitheater’s are at times interrupted by asymmetric inclusions of the volumes that liven up the predictability of the ascent: as if this place got a fair share of chaotic outlaw construction, even though some of the parallelepipeds have stained glass windows: they lighten up the library situated behind the benches of the central amphitheater. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44Left and right of the dark closed volumes, appears a very light white portico before the glass entrance to the main lobby – actually, this is the official main entrance, with a cafe and the museum’s souvenir shop flanking it from the sides. From the foyer, the main staircase starts: it is covered by a succession of three striped glass volumes, diagonally ascending towards the memorial. The architects call this large roofed staircase “habitable”, and reserve for it the role of a large museum foyer, treating it as the main public space that unites the entire complex. The central amphitheater with a library inside is also nearby. Together, they look like the Hermitage staircase in the Joint Staff, which also serves for recreational activities and various events – but here the idea was even further developed, getting more space on the slope. From the opposite side, the striped glass of the three volumes that cover the staircase emphasizes the contemporary design of the complex, slightly softening the brutalist look of the complex, often dull, designed in the image of retaining walls, and sometimes really growing from them. The main staircase – broad and spacious, covered in specks of sunlight – is essentially a hyper-pergola. Its crystal insert makes a perfect match for the name of the cape.  The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44The other main staircase – conversely sharp and determined, like a spike or a rapier – leads from the south corner (and from the city’s central market) directly upwards, to the Sevastopol Hall of Fame, the silhouette of the “Bayonet and Sail” monument lurking in the distance. This is an alternative direction and another connection to the city: on the imagery “avant-garde” master plan it looks like a long diagonal plaque. The “calm, cool, and collected” diagonal staircase can be interpreted as the Walk of Fame of sorts, implying the concentrated movement of ascent or descent, unlike the broad movement of the main staircase – the public space.  The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44Actually, the Hall of Fame is quite a laconic construction that crowns the hill. It looks megalomaniac, yet at the same time lightweight, not soaring upwards but, as Nikita Yavein stressed, calmly occupying its place; it simply is. The four large pylons surrounded by a barely palpable contour of glass walls carry the “awning” roof with a skylight in its middle – something like an oculus or maybe a compluvium; together, the whole composition looks like a giant cup. The hall becomes a logical continuation of the educational and museum center – its symmetry easily summarizes and balances out the conglomerate of the structures standing on the slopes, like the main temple of the ancient city would have. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44Yet, at the same time, the complex is also a park of sorts. One will be able to walk over the roofs of the volumes; strings of cypresses alternate with garden spaces, very much like the Egyptian hypostyle halls. This environment is designed for peaceful contemplation. The park is an important constituent element of the project, and the very fact that it is not added somewhere on the side but permeates the complex from end to end, on the one hand, is giving it a semblance to the Renaissance palaces, where, wandering around the halls and passages, you suddenly find yourself in a little garden on the roof of the second, and sometimes even the third floor: let’s take, for example, the Mantova Palazzo Gonzaga, not forgetting, at the same time, that the prototypes of Renaissance palaces are antique ones, while the later reminiscences of them were reflected in the Crimean Emperor’s palaces.  The functional zonesCopyright: © Studio 44 The volumetric solutionCopyright: © Studio 44 Axonometric plan at elevation 2.250. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Axonometric plan at elevation 6.750. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Axonometric plan at elevation 13.00. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Axonometric plan at elevation 20.00. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Axonometric view of the museum and exhibition complexCopyright: © Studio 44 Section view 1. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Section view 2. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Section view 3. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44 Section view 4. The museum and educational complex and the Museum of Fame of SevastopolCopyright: © Studio 44On the one hand, the park constituent element, just as the public one, makes the project particularly relevant: the museum of avant-garde art, grown into the terraces park on the slope above the sea, comprising a whole number of functions meant to satisfy the tastes of all sorts of visitors, is as contemporary as it can ever get. And it’s also a great thing that contour-wise, and imminently, this version of contemporary architecture does not forget about its roots. |

|