|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 15.07.2019 | |

|

Igor Yavein. The Architect of Traffic Flows |

|

|

Natalia Koriakovskaia |

|

| Studio: | |

| Company: | |

|

Oleg and Nikita Yavein created a website about their father, Igor Yavein: it contains the full archive of the projects designed by this master of avant-garde, the founder of the transportation hub theory that anticipated its time by decades, and the author of the book about the architecture of traffic flows that is still relevant today.  Igor Georgievich Yavein, 1903-1980

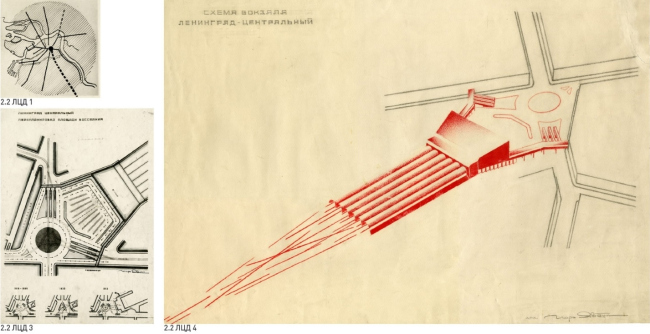

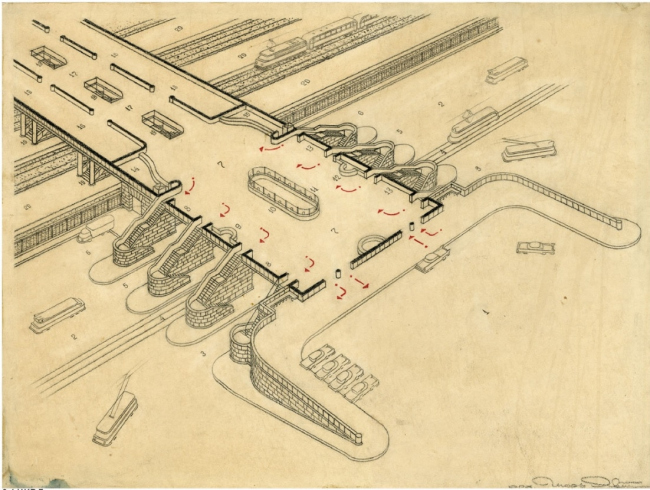

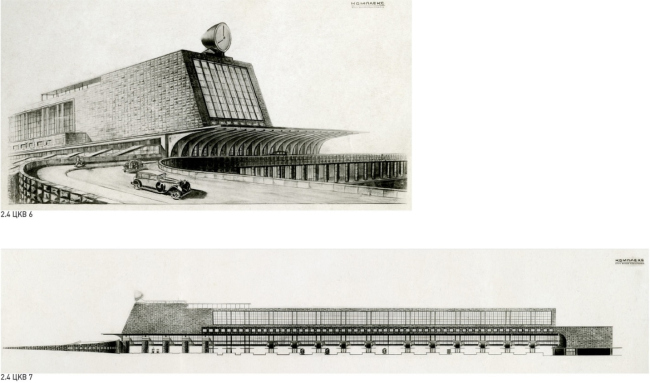

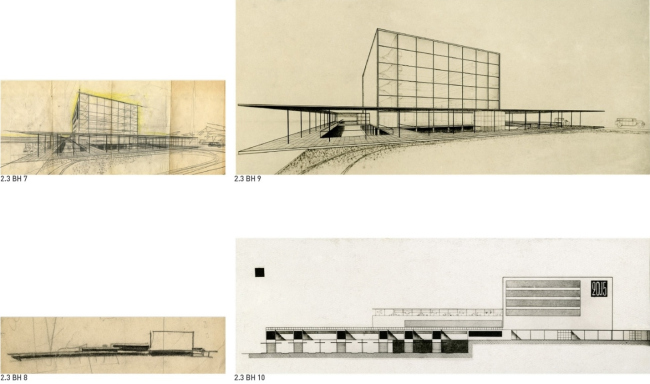

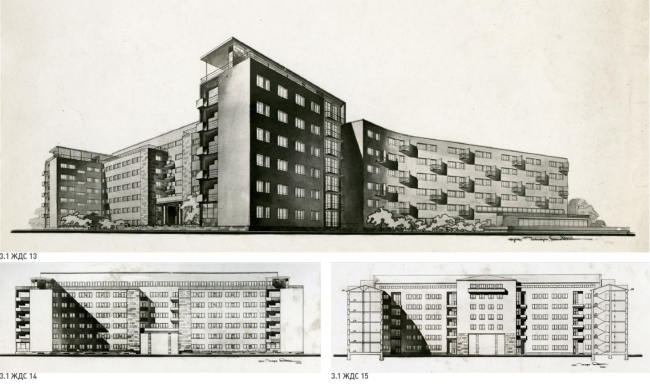

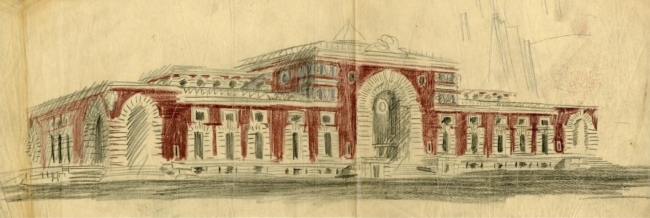

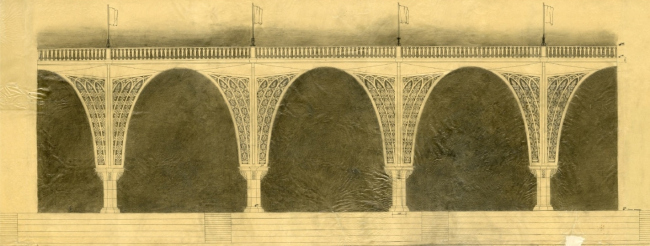

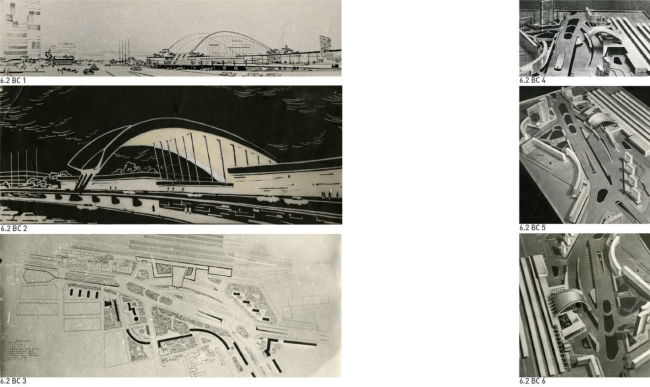

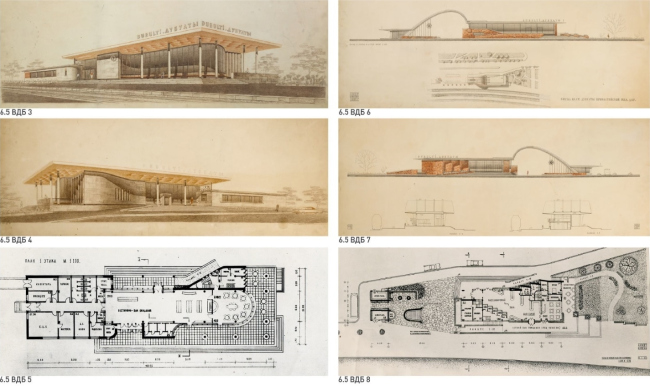

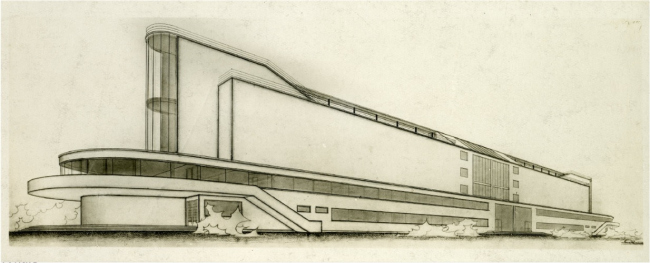

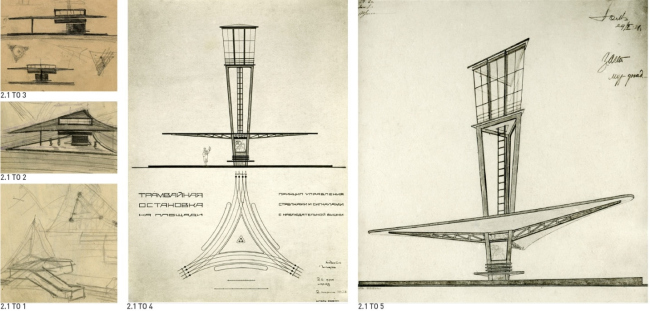

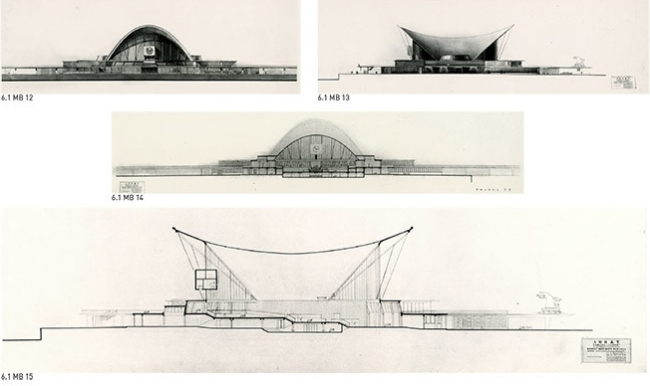

Website: igoryawein.ru All of the materials collected on this website belong to Igor Yavein’s personal archive, and will later on be included in a book by Oleg Yavein, in the course of preparation of which this website appeared. About the architect. Igor Yavein, the pupil of Alexander Nikolsky’s, became known for his innovative approach to designing transportation facilities. In the competition for the best design project of Moscow Kursky Railway Station, he, for the first time in the history of Soviet Architecture, interpreted a railway terminal as a hub that connects different kinds of transportation – from the metro line up to a small airfield on the roof. In his project bearing the motto of “Complex of Seven Types of Transportation”, this railway terminal presents itself as a multilevel structure, whose architecture essentially determines the traffic flows, and is determined by the traffic flows as well. In this competition, Igor Yavein got the highest second prize, the first prize being awarded to nobody. This project was decades ahead of the needs of the 1930–40’s, and looked utopian to many experts of those days. However, in 1964, Igor Fomin recognizes Yavein’s project as the design code for transportation architecture, and in the 1960–70’s Igor Yavein gets back to the ideas of his early years. The choice of profession Igor Yavein was not a hereditary architect – he was born to a family of an epidemiologist, the professor of the Emperor’s Clinical Institute of the Great Princess Elena Pavlovna, George Yavein and his wife, Poliksena Shishkina-Yavein, who was a social activist and the chairwoman of the Russian League for Women’s Rights. Oleg Yavein, who wrote for the website a detailed biography of his father, believes that the cult of serving science, which reigned in their family, later on visibly manifested itself in architecture, becoming the moral basis for their creative method: “For these people, a strong belief in the intrinsic perfection of Nature and the unconditional value of Cognitive Reason was closely connected with the idea of Progress and a peculiar cult of the natural origin in us as human beings, and this complex symbiosis was naturally transferred to their life and art. Igor Yavein found this symbiosis in avant-garde architecture or, to be more precise, this is how he interpreted this architecture for himself”. Igor Yavein did not follow in his father’s medical footsteps, and entered LIGI (Leningrad Institute for Civil Engineering), studying in his first year in the studio of professor Andrey Ol. In his third year, Igor meets his main mentor – the academician Alexander Nikolsky, a brilliant representative of avant-garde architecture and an inventor of a highly individual creative approach. According to Oleg Yavein, father always called Alexander Nikolsky a teacher with a capital T.  The Museum of Agriculture. 4th year of Leningrad Institute for Civil Engineering, 1927. The museum collection of Leningrad Institute for Civil EngineeringCopyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita Yavein The tram stop. Scientific advisor – A.S.Nikolsky. The museum collection of Leningrad Institute for Civil EngineeringCopyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita Yavein“Time was jam-packed back in those days; years felt like epochs, and our student works would sometimes become milestones for us” – Oleg Yavein writes about the period of his father’s life from 1923 to 1927. Once, towards the end of his course, Alexander Nikolsky gives the young Igor Yavein a task to inscribe a tram stop into a narrow triangle of railway tracks, saying “Let’s see if you can find your way out of it”. And the pupil makes a brilliant study that flawlessly conveys the dynamic image. Later on, these hidden dynamics and rhythmic motion will become a signature feature of all of the transportation facilities that he designed. His project of Museum of Agriculture (1927) displays his unique creative approach that Alexander Vesnin will later on call “new organic architecture”. Remaining a constructivist, instead of fracturing and breaking up his architectural volumes in order to single out functional blocks, Igor Yavein prefers to create them within a single unbroken and flowing shape. Lenigrad Central. Diploma paper 1929 – 1930Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinThe competition for Moscow Kursky Railway Station / 1932 This competition became an important milestone in Igor Yavein’s creative career: it was in that competition project of Moscow Kursky Railway Station that he first proposed “the idea of streams”, which the architect further developed in his dissertation and implemented in his subsequent projects. Still in his diploma paper entitled “Leningrad Central Railway Station”, Igor Yavein began to develop the idea of a transport facility as a complex interchange hub, whose form making is determined by various pre-calculated traffic streams. As Oleg Yavein writes, Kursky Railway Station presented itself as a “multilayered bridge thrown over the railroad tracks, with a ship deck roof and sprouting ramps, overpasses, driveways, escalators; an image that anticipated one of the key branches of transportation architecture”. Moscow Kursky Railway Station. 2nd (higher) prize at the All-Union competition, 1932Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinMoscow Kursky Railway Station. 2nd (higher) prize at the All-Union competition, 1932Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita Yavein“This was more than just an idea. The structure, the functional diagrams, the outward appearance – our father elaborated on everything in fundamental detail – Nikita Yavein reminisces – What was written in his book that was published in 1938, is still absolutely relevant today. Even today few people seem to realize that a railway station or a railway terminal is not a “house” in the traditional sense of this word but rather a casing, a shell for the transport and pedestrian flows, a hub where people switch from one kind of conveyance to another”. The railway station in Novosibirsk, 1930. All-Union competition. 2nd prize.Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinDesigning railway stations becomes Igor Yavein’s main specialty. In 1930, he developed an experimental competition project of a railway station in Novosibirsk – a very modern-looking “hypercube” building that covered various traffic streams that were spaced apart. “Constructivism after Constructivism” Igor Yavein allowed himself to remain a constructivist even after the Stalin epoch of neoclassicism set in. His manifesto project of that period (1933-1941), which Oleg Yavein jokingly called “constructivism after constructivism” was the Svirstroy housing complex in Leningrad, one of the last “specialist community houses”. Igor got this commission winning a competition in 1932 but by the moment the construction began in 1938, Russian architecture was already ruled by the neoclassical style. Nevertheless, the house was essentially avant-garde – the asymmetric façade plan, the cutaways at the corners, filled by balcony recessions, the absence of “unemployed” columns, and “excessive monumentalism of form”, as the author himself was wont to say – everything indicated its relation to the architecture of the 1920-30’s. The housing project in Leningrad. A competition project. THe first prize, 1932Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinThe housing project in Leningrad. A competition project. THe first prize, 1932Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinThe epoch of neoclassicism still left its mark on the creative work of this passionate constructivist. In 1945, Igor Yavein wins the competition for designing a railway station in the city of Kursk (not to be confused with Kursky Railway Station) – presenting its building as a triumphal arch at the entrance to the city, still devastated by the Nazi troops at that time. And it is the victory imagery that this classical symmetrical construction was based upon, the most solemn and powerful of all archetypal forms. During the years of postwar reconstruction, this same Moscow–Kursk railroad line gets a whole string of typical railway stations for 50 and 100 people, designed by Igor Yavein. The railway station in Kursk. 1945 – 1952Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinHowever, in the competition project for designing a railway station in Veliky Novgorod, for which he got the first prize in the same year as he got for the Kursky Railway Terminal, the architect again distinguishes himself as a rightful heir of the avant-garde tradition, alloyed, as Oleg Yavein writes, with “archaic” forms of the unique Novgorod and Pskov architecture. The architect uses the archaic elements, explaining this by the fact that in the postwar Novgorod, the architect essentially had at his disposal the same construction materials as 600 years ago. However, a keen observer may notice that these forms conceal asymmetric avant-garde composition of volumes that was explained by the presence of functional and motivated cause-and-effect connections. For this project, Igor Yavein’s friends jokingly called him a “constructivist who hid himself in Novgorod underground”.  The railway station in Veliky Novgorod. 1945 – 1952Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinThe railway station in Veliky Novgorod. 1945 – 1952Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinStadium on the Krestovsky Island: Nikolsky and Yavein The grand-scale project of Nikolsky’s – the stadium and the seaside Park Pobedy (“Victory Park”) on Saint Petersburg’s Krestovsky Island, while partially implemented before the Great Patriotic War, was suspended in 1952-53 because of the architect's illness. Then Teacher offers his Student – Igor Yavein – to take part in completing some of the project works in the second stage of construction. Igor Yavein joins the project team, does the project details in the vein of his Teacher’s style, and does his best to keep the original ideas unchanged. Oleg Yavein remembers this period in the life of his father quite vividly. “Father helped Nikolsky with designing the Kirov Stadium when Nikolsky fell seriously sick. I was a little boy back then, sitting next to him, and drawing a stadium too...” The stadium at the Krestovsky Island. Developed by Nikolsky. 1952-1954Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinContinuity of Generations In the 1950–1970’s, Igor Yavein again returns to designing “expandable railway stations” but now the theme of the flows merges with the ideology of the epoch of industrial construction. The so-called “integrated home-building factories” are built, new possibilities for expansion and transformation appear. In 1960, Igor Yavein presents for a competition an “avant-garde” project of the Leningrad Sea Terminal, three years later taking part in the competition for the railway terminal and its square in Sophia, Bulgaria. The imagery of this project will later on resurface in the railway station built at Latvia’s Dubulty, which Igor Yavein already designed together with his son, Nikita. This railway station, which served three kinds of transportation at once – railway, busses, and riverboats – was finished by 1977; its resilient arc straddling the railway tracks looks truly impressive. Later on, a similar motif would again resurface in the projects by Studio 44.  Sea terminal in Leningrad. A competition project. III prizeCopyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinThe railway station in Sophia, Bulgaria. 1963Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinFather’s personality charm was tremendous – Oleg and Nikita Yavein are reminiscing, so their own choice of profession was a natural one. The diploma paper that Nikita Yavein did in the Saint Petersburg University of Architecture and Civil Engineering was, according to his own words, a continuation of the ideas proposed by his father. The railway station in Dubulty, Latvia 1977Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinThe railway station in Dubulty, Latvia 1977Copyright: © Oleg Yavein and Nikita YaveinIgor Yavein’s book “Architecture of Railway Stations” was first published in 1938, and its ideas about the influence of traffic streams on designing transportation facilities determine the architecture of railway stations up to the present day. |

|