|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 04.02.2019 | |

|

Geometry of Integration |

|

|

Alyona Kuznetsova |

|

| Studio: | |

| Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural Studio | |

|

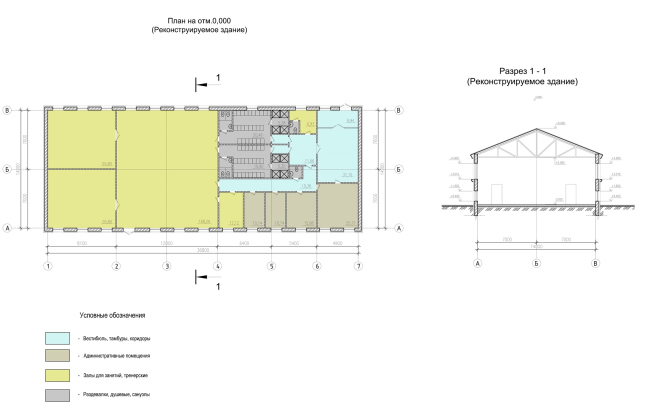

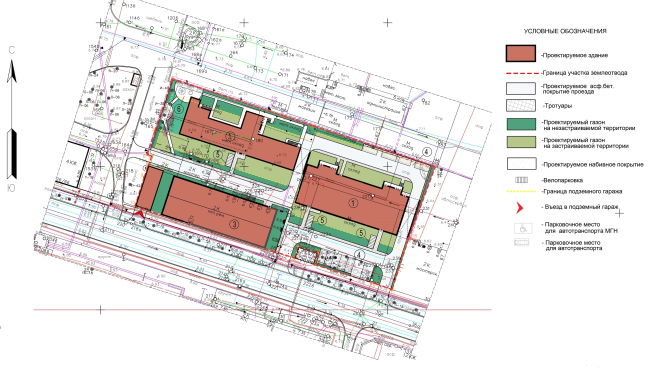

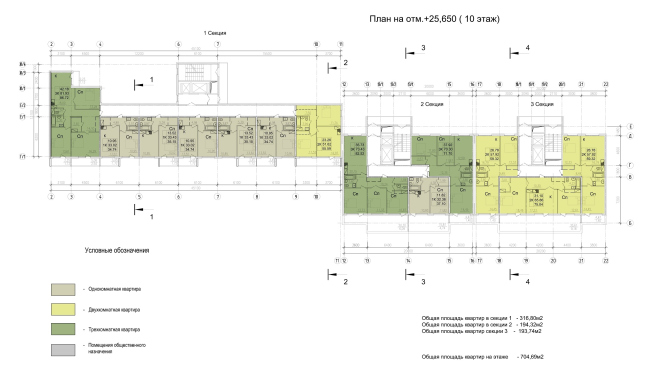

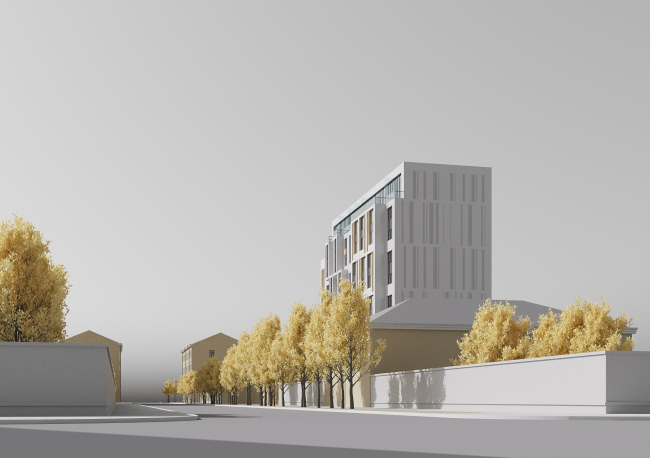

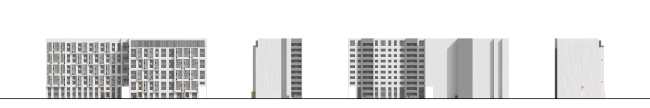

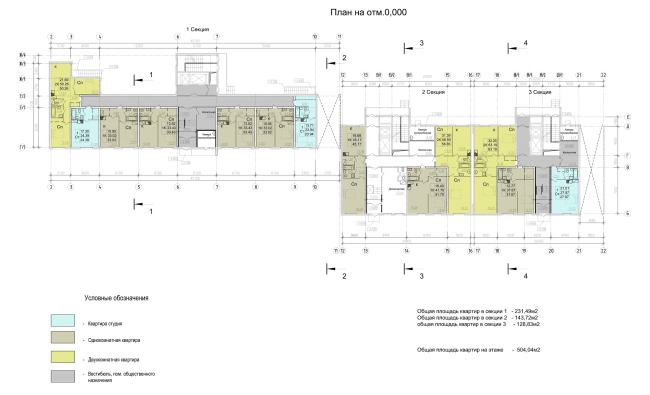

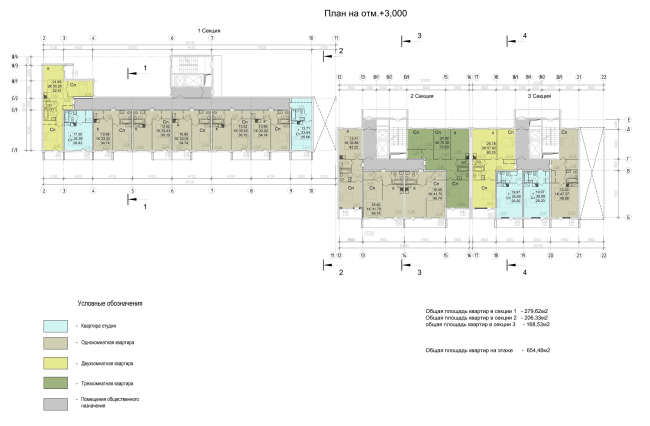

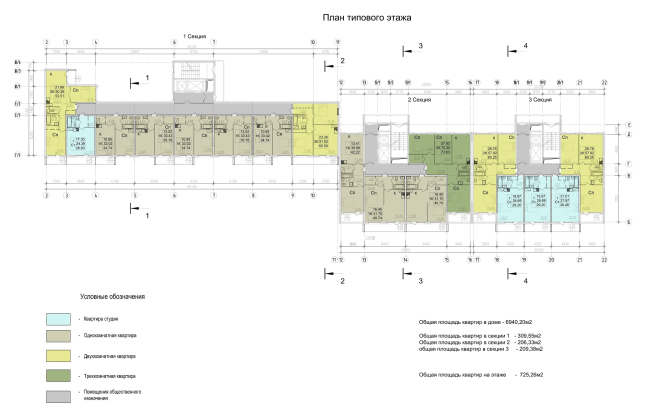

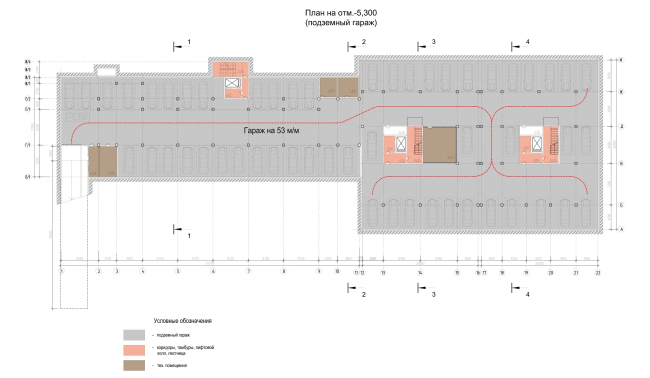

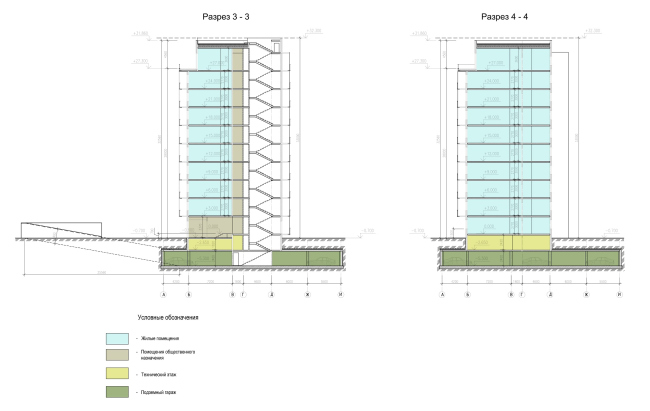

The project of a residential complex situated behind the Bypass Channel in Saint Petersburg is based on the architects’ search for the optimum balance between the construction regulations, the surrounding context, and their belief in the relevance of pure modernist architecture, free of any signs of stylization. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe construction site is located in the historical part of the city that back in the day was called – not far away from the Ligovsky Avenue and the Obvodny Kanal metro station, behind House 28 on the Prilukskaya Street. Currently, in the opposite corner of the block, they are building the “House at the Karetny Bridge”, also ten stories high, all the other buildings on the block being significantly older – tenement houses of the early XX century, one Khrushchev-era house, warehouses and factory buildings, all situated in a rather chaotic manner in respect to one another. About the same kind of morphology is to be observed in the neighboring blocks. The most noticeable nearby building is the red-brick “Palace of Culture of the Railway Workers” (the Soviet term for “community center” – translator’s note) that bears the status of a heritage site of federal importance, and the tallest local building is the “automatic telephone station” that shares the space across the future residential complex with a no-name park. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe house that was built in 1905, which is also situated on the land site and borders on the red line of the Prilukskaya Street is in fact one of the buildings of the former mica factory, which since the early 2000’s has been occupied by offices. There are plans for clearing the building from all of the later additions, renovating its façades, restoring the gable roof, and giving it a new sports function. Since the floor plans do not bear the protected status, the intermediate floors will be dismantled altogether – this will yield enough space for three light and spacious gyms, as well as all the necessary auxiliary premises with a total floor space of about 500 square meters. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Plan of the reconstructed building © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe leader of the architectural firm, Anatoly Stolyarchuk, confesses that working in the historical part of Saint Petersburg requires pinpoint accuracy: in order to gracefully introduce a new building into the already-formed city fabric, one must take into account lots of factors, and sometimes mutually cancelling requirements. Specifically, the architect shares that he would have been happy to align all the residential buildings along a single line, but this plan was thwarted by the insolation norms – the first floor in this case does not get enough of ambient light. The “coefficient of complexity” also rises due to the fire safety regulations, the logic of the driveways, the necessity to ensure a sufficient amount of parking spots, and providing enough room for a playground. In addition, the architect says, meeting the developer’s brief with the predetermined set of apartments and at the same time coming up with decent architecture is like walking on a knife’s edge. Such situation the architects oftentimes compare to a mathematical problem or a jigsaw puzzle. The “equation” of this particular land site could be solved in two ways: by placing the new building behind the old one and perpendicular to it, or parallel to the Prilukskaya Street. The first option was discarded by the architects because they reasoned that making the building face the street with one of its side ends would be the wrong thing to do. Therefore, the buildings are positioned alongside the street and slightly recede into the site. This gives a fair amount of air to the historical building, masking the height of the neighboring buildings, takes them a little further away from the street with its inevitable cars, and opens up more windows on the south side. This way, the red line within the confines of the site is all-but-crossed by the laconic pavilion of the underground parking garage entrance, the historical building, the substation, and the parking lot. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Master plan © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioAfter all of the restrictions were addressed, the architects came up with a two-part composition of the residential complex. The section behind the historical building is narrow and belongs to the rare-for-Russia “gallery” typology – all of the apartments in it are facing the Prilukskaya Street because making windows in the north wall would have been impossible because of the proximity of the border of the neighboring site. Therefore the gallery turned out to be without windows, like a corridor, while the outside wall turned out to be Empire-style-laconic. However, the absence of windows allowed the architects to find near this wall of the house a place for the playground because a blind wall cancels the regulation 12-meter setback. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Plan at the mark +25.650 © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe second building, which is pushed a little bit closer to the Prilukskaya Street, consists of two sections; it is thicker, and its windows overlook both the street and the yard. Its tenth upper floor is fully glazed and is set back from the edge, forming a number of penthouses – apartments with a slightly larger floor space and commanding fine views of the city. The receding upper floor of the outstanding building is included in the carefully calculated play, thanks to which, when viewed from the crossing with the Tambovskaya Street, the cornices of both units of the new building align practically into a single line with each other and with the cornice of the pseudo-Empire-style house of 1899 standing at the crossroads. The modern façade pattern, which unites pairs of stories along the verticals, also echoes the rhythm of the surrounding houses: four tiers of visually paired windows echo the four floors of the historical building (even though we will note at this point that in the development drawing the new building is almost twice as tall as its historical neighbor). The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Development drawing © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe façades are designed in a single key. The architects believe that the new construction must fit in with the scale of the existing buildings, but at the same time they observe the self-imposed prohibition against working in “pseudo-styles”: in order to tie in the old and the new at a deeper level, the architects, according to Anatoly Stolyarchuk, place their bets on the rhythm, proportions, and plastique. The plastique is based on the active “layered-like” character of the street façade, which helps to mask and soften the “stair” that appears between the two buildings. The groups of stanzas in the east and west parts forms outstanding slabs of risalits that flank the volumes; as for the stanzas in the central part, closer to the point where the two buildings come together, these are situated in an exquisite staggered order – this way the architects made sure that they avoided the unpleasant “thermometer” look. All of the stanzas are marked with thin vertical strokes – a visual technique that reminds us about the airing slits, while in fact it is meant to give the façade a more slender look, highlighting its “noble” character. The stripes on the “staggered” stanzas are placed in a regular order, while on the projections they alternate, placed sometimes on the left and sometimes on the right; they intrude into the horizontals of the intermediate floors and take on an Empire-style beige color that becomes the basis for the coloristic dialogue with the historical city. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe same soft ochre color is picked up by the casings of the air conditioning units set before the windows in the gaps between the stanzas, and by the U-shaped marquees above that hallway entrances. The main color of the building is light-gray to the point of white, yellow inclusions forming the décor – and the result looks as if its façades “overturn” the logic of the walls of the old Saint Petersburg, and, specifically, the already mentioned pseudo-Empire building: it has white details set against yellow background, and in our case the picture is curiously inverted. It is planned that the façades will be stuccoed, which will also will make them fit in with the surrounding buildings. The housing project on the Prilukskaya StreetCopyright: © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioIt is plain to see that the slender and “tiled”, light-grisaille house echoes other projects by Anatoly Stolyarchuk – ones on the Esperova Street and on the Krasnogo Kursanta Street – all of them to a certain degree can be considered “representatives” of the contextual modernism, noninvasive author architecture, geometrically inscribed into context. We will also note here that the house, actually, rather tall, does everything not only to address its architectural context but also to “dissolve” in it, decreasing its volume and its influence – for example, by means of gray pixel strokes in its side ends. Meanwhile, here, behind the Ligovsky Avenue, at the border with large-scale industrial parks, 10-story height, even by the standards of Saint Petersburg, looks quite self-consistent. The housing project on the Prilukskaya Street © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Plan at the mark 0.000 © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Plan at the mark +3.000 © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Plan of the standard floor © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Plan at the mark -5.300 © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural StudioThe housing project on the Prilukskaya Street. Section views © Anatoly Stolyarchuk Architectural Studio |

|