|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 24.12.2018 | |

|

The “Barn” Method |

|

|

Darya Gorelova |

|

| Studio: | |

| Khora | |

|

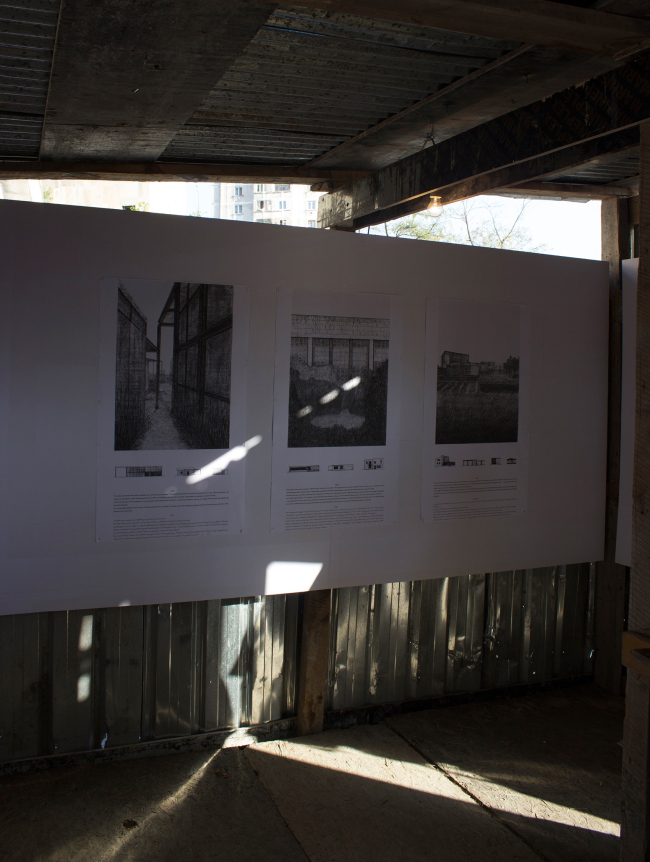

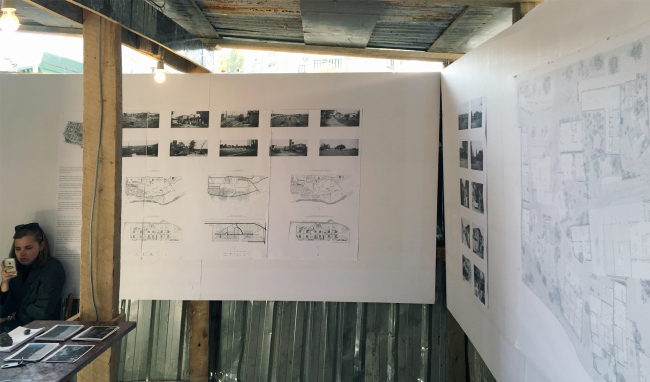

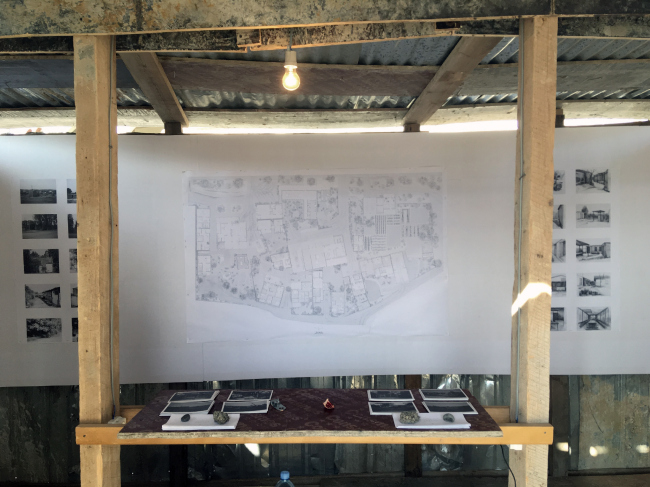

The architects of XOPA architecture bureau exhibited at Tbilisi Architecture Biennial with a “barn” pavilion turning it into a “manifesto of architecture without an architect”. The hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAThe first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, established in 2017, took place from October 26 to November 3 and consisted of an exhibition, installation, film presentations, and a symposium, which, among other people, included Nina Rappoport, Alexander Brodsky and Reinier de Graaf. The subject matter of the discussion was the post-Soviet space, new economies, and the professional education issues in remote areas. The “hulula”, built by the XOPA architects, hosted an exposition of their research of one of the peripheral areas of the Georgian capital, and at the same time a manifesto of “straightforward” architecture and a reminder of the numerous shacks and outlaw barns that, according to the authors, tend to surround large southern cities, although, come to think of it, this is equally applicable to northern cities as well – it’s enough to remember the presentation by Alexander Lozhkin about the esthetics of whole areas of outlaw construction at the outskirts of Novosibirsk. The authors deliberately stepped back, refraining from making any draft designs, putting together some odds and ends, only giving the builders verbal recommendations and full freedom of action, and then simply observing the process. Meanwhile, the hulula turned out just great – not some shabby roadside affair but a whole little house with a front porch and sturdy doors, coated with slightly peeling paint. On the inside, there are supports, a table, and tablets displaying the project – quite a decent exhibition booth. On the outside, there is glittering corrugated metal that resonates with brutalist and slightly sloppy post-Soviet and late-Soviet environment – at night, the backlit metal glows like a lamp, and it’s plain to see that, in spite of the absence of any draft designs, the authors are admiring their work: the way it glows, lit by spotlights, in the night, and the way the specs of sunshine penetrate through the walls by day. The structure is not at all devoid of esthetic qualities, it looks simply beautiful – essentially, we are exposed to the esthetics of outlaw construction, which is something that architects around the world generally frown upon and call on to clear our cities from it. The hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAThe hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAThe hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAMeanwhile, as is known, in some architectural circles the barn has long since been estheticized, and, of course not only on the post-Soviet territory but in modern art in general. In our case, however, it takes on a particularly lyrical character of a “true” and “warm” art as opposed to fake or “tasteless” kind of art. Once back in the day, at one of the Arch Moscow exhibitions, Alexander Brodsky, getting a prize for his pavilion of vodka ceremonies (or maybe it was for “95 % ABV” restaurant, I cannot recall which) said something to this effect: I am really surprised to be getting all sorts of prizes for the barns and shacks that I design. This says it all about the meaning and the phenomenology, and the prizes, and the constantly appearing installations, and even about the custom designed private residences that do sometimes show an odd fragment of “barn” esthetics, Alexander Brodsky, of course, remaining its unparalleled master. The installation designed by XOPA fits in pretty nicely with this venerable circle generally and specifically – the good old doors with pieces of plywood serve as a great visual hook. Probably, the most remarkable feature of this “work of art” is the stress that the authors laid in the method itself, as if making an attempt to institutionalize it. Instead of admiring the numerous layers of meaning, what we seeing here looks rather like taking the theme to its logic maximum: no, the esthetic sides are not forgotten but a large part of the concept is occupied by the building experiment, which turns this installation into an “Ambassador Plenipotentiary”, a representative of all barns, shacks and huts at the architectural biennial, or a “model” shack (like, for example, they exhibit samples of log constructions at markets of building materials). It is this coup de maître that makes the whole thing so exciting, like an attempt to explore a whole new theme. Below, we are giving the floor to the authors of the installation: Hulula: straightforwardness as a method Within the framework of the first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial entitled “Buildings alone are not enough”, the XOPA architects showcased a “hulula” (which translates from Georgian as a “makeshift shelter” or “shack” or “toy house”) – an expo pavilion or an installation that hosted a specially prepared research project devoted to one of the peripheral areas of Tbilisi. Our installation is essentially a manifesto of “architecture without an architect”, brought into the public eye. Such structures, due to their being “one of a kind”, often remain under-researched and fall short of becoming a subject of the professional architectural discourse – but they are still an indispensable part of the history of development of the southern post-Soviet cities, including Tbilisi. In our vision, hululas can be considered to be the informal cultural legacy because they reflect with perfect accuracy and adequacy the economic, political and social context in which they exist. The installation was placed in Tbilisi’s district of Gldani on the square in front of the DKD bridge (of late-Soviet construction, partially inspired by Ponte Vecchio) in the temporary truck parking lot. The hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAWhat was important was the method and the order of construction procedures. The architects used the local frequently-used low-budget building materials, as well as leftovers from nearby construction sites, and a few elements of dismantled infrastructure projects. The working group consisted of local builders and artisans. The construction method was essentially similar to the kind that is applied for construction of most of projects that we have been studying: without a design project, without draughts, without a construction permit, and, consequently, without any author control. We as architects played both the part of a client and a third-party observer because we only gave the builders verbal explanations and guidelines. The course of construction as an indispensable part of our project was photo and video documented. The builders were entitled to freely interpret our ideas, which allowed us to keep the desired straightforward purity of our concept. Moreover, we borrowed the electricity from a nearby shoe repair shop in exchange for the building materials that were to remain there after the dismantling of the hulula. The hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAThe hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAThe hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAThe hulula at The first Tbilisi Architecture Biennial © XOPAYet another important aspect was the controversial and at the same time harmonious correlation between the interior and exterior of the structure. While on the outside the shack is covered with profiled steel sheets that reflect the mottled surroundings, the interior design is dominated by materials of wooden origin – OSB boards, floor boards and paper. Due to its material and volumetric properties, as well as its location, this structure, whose main purpose was to conceptually merge with the surroundings and at the same time grow up from it, turned out to be so attractive looking that rare a passerby could resist the temptation of stopping by and having a glass of home-made wine and chacha (the local kind of grape brandy). The authoring team: XOPA (Mikhail Mikadze, Oyat Shukurov, Alexandra Ivashkevich, Elizaveta Lartseva, Vazha Magradze) XOPA website: / social media: xopapraxis About the Biennial: Participants of the Biennial: |

|