|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 19.12.2018 | |

|

Maria Panteleeva and Sasha Gutnova: “What we are missing is the idealism of the “New Element of Settlement” working group”. |

|

|

|

|

|

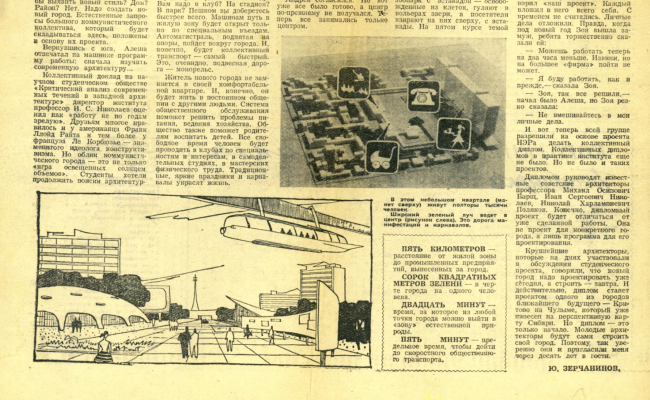

In this issue, we are talking to the curators of an exhibition and an educational project devoted to the “New Element of Settlement” phenomenon, as well as about its specifics and relevance for the realities of today. Sasha Gutnova and Maria Panteleeva at the setting up of the exhibition at Schusev State Museum of Architecture. Photo by Timofey MoskovkinArchi.ru: The project entitled “New Element of Settlement: History of the Future” includes not only an exhibition but also a film, a book, a scientific symposium, and a set of lectures. How did the idea of such a grand-scale project come about? Maria Panteleeva: The idea of this project sprang up in two different parts of the world – in Paris and New-York about three years ago. Each of us came to it her own way. I am an architect – I graduated from Moscow Institute of Architecture, and then I went to the USA, where in Princeton University I defended my thesis devoted to “New Element of Settlement” (hereinafter referred to as “NER”), the town-planning concept that was born in the late 1950’s – early 1960’s in Moscow Institute of Architecture. I started working on my thesis six years ago, and originally it was about experimental Soviet architecture but it the process I really got into the topic of NER, and ultimately I totally switched over to it. In the course of my research, I learned that there were archives of NER in Moscow, in the family of Aleksey Gutnov, one of the founders of this approach, and I got in touch with his daughter, Sasha Gutnova. After we met, the idea of this exhibition was born. By that moment, working on my thesis project, I already decided to produce a film about NER, and I got a grant from Graham Foundation for its production. I would meet with the members of the NER working group, also staying in touch with the students of Moscow Institute of Architecture who, as it turned out, knew nothing about that phenomenon, in spite of the fact that Ilya Lezhava – one of the key ideologists of the group – was an extremely popular professor in that institute. This is how we came to a conclusion that we had to make not just an exhibition but a full-fledged educational project in order to get as many people as possible exposed to the phenomenon of NER, whose ideas are still vital not only for Russia but also abroad, and are still influencing architecture around the globe. Sasha Gutnova: To me, this whole thing is both personal and professional. I also went to Moscow Institute of Architecture, then I was a postgraduate student in France where I majored in urban planning. As a matter of fact, I only discovered for myself the creative work of my father, Aleksey Gutnov, one of the key figures of NER, many years after his death: when he passed away in the mid-1980’s, I was only 16. A few years ago, I started sorting out my family archives, and, now seeing them through the eyes of an experienced architect, I realized that this whole NER narrative was worth recollecting, studying and saving it for the younger generation. Especially today, when we finally started caring about our material legacy of the Soviet modernism but often tend to forget about the kind of legacy that is ideological and theoretical that is just as much worth saving. We are asking ever fewer questions about the future because we are too busy with answering the questions of the present. Essentially, any architect is creating a future, and NER is a vivid example of how someone can be a visionary in the field of architecture. A fragment of an article in "Komsomolskaya Pravda" devoted to the diploma project of NES. From the archives of Andrey ZvezdinThere is a number of articles published online where the phenomenon of NER is explained in a rather extended and complicated form. After you read these articles, you still cannot answer the question as to what NER essentially was – a town-planning theory, an independent project in its own right, or a team of like-minded people. How would you answer that? Maria Panteleeva: As a matter of fact, the idea of organizing an exhibition devoted to NER grew into such a big project specifically because we ourselves were trying to find the answer to that question. The members of NER call it a “school”. A school of thought. And this is indeed the case, even though a lot of architects haven’t got a clue that they are actually part of this school, being under the influence of their teachers. Probably, you could say that it’s a school of architectural philosophy. Sasha Gutnova: I also asked myself this question more than once. I think that NER can best be defined by the term “movement”. First of all, movement as some vector and unity: this was the time with a very special atmosphere of its own, people would dream about the future, and they had great hopes for it, and NER in this sense was no exception – it united people who believed they could change the world. Second, this is motion as progress. You understand this particularly well in the context of the late 1960’s. When the era of “stagnation” began, the members of NER were still “moving forward” their theory and their school of ideas. The best proof of that is the professional career of Ilya Lezhava and the work of Aleksey Gutnov in the work of perspective research of Genplan of Moscow. It is amazing but this movement is still going on, only in a different way. This tradition is continued by Alexander Skokan of Ostozhenka Bureau, Vladimir Yudintsev, Stanislav Sadovsky, Sergey Telyatnikov, Nikita Kostrikin, and others who teach at Moscow Institute of Architecture. The pavilion of the special project "New Element of Settlement: History of the Future" at the 23rd International Exhibition of Architecture and Design "Arch Moscow", 2018Can you put in a nutshell the basic principles of NER? Maria Panteleeva: The first principle is the humanistic vision of the city. Generally speaking, in the postwar era humanism started returning to cities all over the world, and we can observe this revival all across Europe. An important part of their theory was breaking away from the concept of an endlessly growing city – a phenomenon that we have long since been observing in our reality, and more uniform distribution of the cities in terms of their territory, a lot of attention being paid to developing them as cultural centers. According to the NER ideologists, any city was entitled to be a full-fledged cultural center, not just such giants as Moscow or Saint-Petersburg. Sasha Gutnova: The key notion of this theory is, of course, the NER (New Element of Settlement) itself, an alternative to a city that spreads away like an ink blot. Second, the future world of NER is a world of humans, not a world of machines: hence the routing of the transport communications and placing the industrial parks outside the boundaries of residential areas. This city is all about communication between people, the space for which is enthusiastically designed by inspired architects. And the third thing that we must remember about NER is the fact that it is the long-term development of this theory that essentially generated the whole lexicon of the modern urbanist, for example, such terms as “framework”, “city fabric”, “cell”, “stable” and “unstable space system”. And, although the NER architects do not claim to have invented these terms, you need to realize that this set of concepts gave birth to discussions and meditations of real people who essentially created it. Actually, this particular topic will be covered by one of the chapters of the that we are going to present at the exhibition. Sasha Gutnova and Maria Panteleeva share with Maria Troshina about the project "New Element of Settlement: History of the Future". Photo by Timofey MoskovkinWhat do you think is the seed that allows the NER ideas to stay around for such a long time and grow again and again in new generations of architects? Maria Panteleeva: I think that this is communication between the members of the group who never lost touch with one another and kept up a constant exchange of ideas. Communication is the key idea of the NER theory: the members of the working group believed that a city was first of all to be based on communication, and not on some system of purely functional elements of architecture. Sasha Gutnova: Yes, I agree – it is first of all about high-quality professional communication, loving what you’re doing, and your desire to make a positive difference. Maria Panteleeva: What I think is also important is the fact that they felt like the future residents of this city, all the way starting from their student projects, and the ideas of NER to a large extent reflect their own aspirations, relationships with one another, both personal and professional, and thus the theory never stopped developing. Sasha Gutnova and Maria Panteleeva share with Maria Troshina about the project "New Element of Settlement: History of the Future". Photo by Timofey MoskovkinIn 2008, Moscow Institute of Architecture hosted an exhibition devoted to the diploma project “NER-Kritovo”, and there was a meeting of the members of the group. Everyone recalled with warmth Aleksey Gutnov, who, regretfully, passed away so early, and spoke about him as the main ideologist of NER. Maria Panteleeva: Unfortunately, I did not have the chance to meet him but through the archives, thanks to Sasha Gutnova and her mother Alla Aleksandrovna, I was able to connect with his architectural heritage and get close to understanding the magnitude of his personality. Of course, he was the “cement” and the center of the group. To me, he is a legend, and, to some extent, a mythical figure. A short time before the exhibition, we ran into a handmade book called “Ostrov Solntsa” (“Island in the Sun”), which Aleksey made when he was nine, and in which he, in the naïve style of a little boy that he was, drew the perfect cities of his dreams. This was quite an unexpected and amazing discovery that we will also present at the exhibition. Sasha Gutnova: When my father was gone, I, of course, could not appreciate all the meaning of his work. To me, he was first of all a dad. For a long time, I would put off getting down to sorting out his archives, and when I finally got round to it, it was like knowing the side of my dad that I’d never seen before. I am really grateful to Maria for her interest to this story and I really value her opinion – it is a lot more objective and scientific than mine. In addition to this whole personal involvement thing, NER is also interesting to me as an example of collective work. Because the beauty of this whole narrative lies particularly in joint creative efforts. Aleksey Gutnov could really unite people around himself, and, although I was still young, I felt some amazing quality of communication that was going on around me, when the group gathered in our apartment. The prime movers, the “locomotives” of the group were Aleksey Gutnov and Ilya Lezhava, they were great believers in what they were doing, but every member of the group was just as important. Each one made his own contribution. Ilya Lezhava once shared with me that once they came up with an idea that if the NER group were a bird or a human being, Aleksey Gutnov would be the head, Baburov the heart, somebody else the wings, somebody else the hands, and so on. Each would be a part of the whole that could not exist without this part. This is a very beautiful metaphor, and I think that the main talent and the main achievement of my father was his ability to see people who thought in the same lines with him, and whom he could infect with his enthusiasm. Sasha Gutnova and Maria Panteleeva share with Maria Troshina about the project "New Element of Settlement: History of the Future". Photo by Timofey MoskovkinYour project – the exhibition, the book, the film, and the conference – is something like a monument to NER. Does that mean that NER – at least in the form that you have been speaking about – is now over, and now it’s time for it to be cast in bronze? Maria Panteleeva: Quite the opposite – we want our project to revive the public interest to the ideas and the creative spirit of NER. Things that you will see at the exhibition are part of history, and there is no sense trying to recreate them in the realities of modern life but the history of NER is far from finished. Sasha Gutnova: We perceive the exhibition and the archive research as an urge to explore new things. We would want the visitors of our exhibition, who will read about NER and will hear the voices of the members of the group, think about the future. We want to somehow awaken the spirit of the visionary and the meditations on how we will live in the future. This is specifically why we came up with the idea of the practice-and-theory seminar called “New History to Be” that will gather young architects, urban planners, theoreticians of architecture, sociologists and geographers who will share their ideas about how we see the future of our cities, and about how to make plans not in the perspective of 2022 but in a much more long-term perspective. Today, we are in a desperate need of some idealism and humanism in architecture that were inherent the NER members. We want to believe that our project will become a stimulus to the development of a new vision of the architecture of the future, that it will help people to have dreams about the future once again. |

|