|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 06.07.2018 | |

|

Magda Cichon: “We lived on this for a year and a half” |

|

| Studio: | |

| Blank | |

|

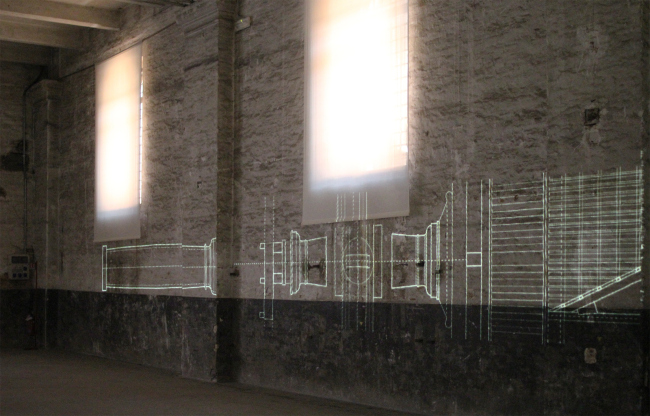

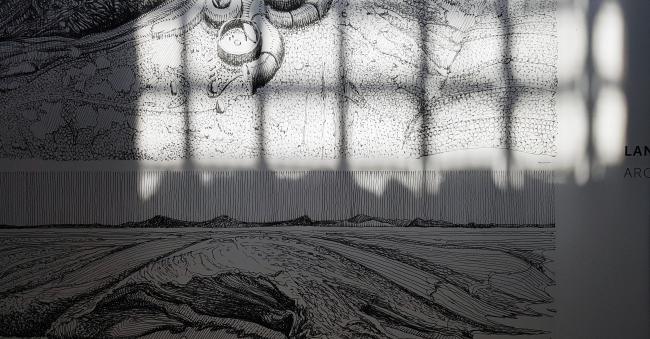

The work done by the curators of the Venice Biennale mostly remains off-screen – the numerous industry reporters that come to the event don’t seem to write much about it. The backstage of this year’s biennale is uncovered by Magda Cichon, the managing partner and the chief architect of Blank Architects, who knows firsthand how it all went along.  Magda Cichon, the managing partner and the chief architect of Blank Architects © Blank ArchitectsMagda, thank you for agreeing to share the secrets of the curators’ backstage work with us! It is always interesting to learn how creative people come to a certain result. It’s not so much a secret as it is a family story. Here is the thing – I am half Irish, and there are also architects in the Irish part of our family. Ireland is a small country, practically the whole of it is concentrated in Dublin, and the biennale curators of this year – the Irish architects Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell – invited two members of my family to take part in the creation of the biennale. And it was them that shared with me how it all went along, and we virtually lived on that for a year and a half. It was interesting to me as an architect to see how the curators’ work was done, and what the end result was. Probably this is the reason why I was not so much interested in national pavilions, and when I talk about the biennale with other architects I recommend them to pay a fair bit of attention to the curators’ pavilions. Before this year’s biennale, the names of Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell were not really known to general public, and even not that much in the professional circles. How come they were chosen to be the curators? Yes, it’s true, they are not on the “star” or the “celebrity” list of the world’s architecture. At the same time, Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell are really good architects. They teach architecture in various universities, they’ve got lots of professional awards, and they make great architecture. This must be the reason why the organizers of the biennale noticed them and invited them as the curators. The curators made in Venice not one but two expositions – one in Arsenale and one in Giardini. How did they organize their work in Arsenale? Some of the Arsenale’s buildings date back to the XII century. These are very old multilayered structures. Once, back in the day, they were used by the military, and now they serve as exhibition venues – architectural biennales alternate with biennales of modern art there. And every year they make some changes to the building: for art events, they create a special space, and the architectural exhibitions are also organized in accordance with their specifics. The curators' exposition in Arsenale. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThe curators' exposition in Arsenale. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThe curators' exposition in Arsenale. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruWhile working with the space of Arsenale, Shelley McNamara and Yvonne Farrell did a tremendous job of making sure they let in enough sunlight. At first, they opened all the doors and windows, even those that were long since forgotten about. They did everything to help the buildings breathe freely. And as an architect, I quite understand their desire to see this space. And, having done that, they began a survey of how this new light and outer effects would interact with the exhibition. How, for example, the exhibition would be affected by the flecks of light from the water in the channel that flows down one of the side façades of Arsenale. And only after they had studied all these details, the curators started thinking about the way to figure out how to inscribe the architects’ works into the space that they got, and how to do it respectfully. The organizers of the biennale did not understand how exactly the exhibition would operate, and how much ambient light would be there in the building at a given moment. The rules say that exhibitions must be lit by cold lights, while sunlight is obviously warm. However, the curators insisted on their solution, and then they mixed up the warm and the cold light. And this play of light was very exciting. The curators' exposition in Arsenale. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThe curators' exposition in Arsenale. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruArsenale hosted the works by the invited architects. What were the selection criteria for the participants of this exposition? This second part of the curators’ task was related to the festival’s theme, which was FreeSpace. And the curators’ approach to the problem of shortlisting the architects is also very interesting. These had to be people who work with art of architecture, immerse themselves in it, and teach students. Yet another criterion was more architects from different countries, including the developing countries of Asia and Africa that nobody had heard about before. The candidates’ portfolios were also a factor – what was their input into architecture that they had made during their practice, and what new themes they explored. So, this biennale opens up a lot of new names. Famous architects were also invited, of course – BIG and Peter Zumthor. All in all, they shortlisted 100 architects. This list was then divided in the middle of the alphabet by the two curator architects, each of them getting 50 architects, very different, and with very different approaches to their work. There were even architects who said that they would just make their installation on the spot. At the end of Arsenale, they built a bamboo pavilion over the water where everyone would wind up to take a rest, discuss what they saw and meditate. Its authors, the guys from Vietnam, just came round and said: “We don’t do projects for such pavilions. We’ve got the art in our hands. We’ve got the materials, and we’re going to make an installation here and now!” This is so vastly different from the habitual approach when you first do sketches, then a project, and then you go over to the implementation stage. How did the curators go about arranging the exposition? Were the expo places that showcased the work of the hundred featured architects defined in advance or were they put together like a jigsaw puzzle? The curators wanted to put the composition together based on how the building worked: how the sunlight and its reflections would fall through the windows, and how the theme would be built up to its climax. The architects’ installations were arranged in such a way as to immerse the visitors into the theme and then give them an opportunity to take a rest: the concentration of the theme gradually becomes less dense. Ultimately, Arsenale got an exposition that could be easily read by the visitors; it took you two days to examine all of the architects’ works and get an impression from every single one of them. What were the curators able to do in Giardini? The exposition of the Giardini pavilion is based on the chain “past-present-future”. Here, in my opinion, the curators were particularly successful in working with the history of architecture. We as architects do a lot of drawing, and it is important for us what goes to the construction site and what doesn’t. Just think back to the times of Le Corbusier, Louis Isadore Kahn, and è Frank Lloyd Wright – there were tons of projects that were never implemented. These projects are seldom spoken about, and the curators brought them back to light. Back in those days, architecture was more of an art than it is now. Everything was on paper, and everything was drawn by hand. The communication between the architect and the client was also different – it was all about letters and telegrams. It is shown in the project that the Japanese did for Venice. Today, you can instantly send your project materials by electronic mail or even by What’s App. And back in those days an architect would have to send his sheet, wait for an answer, make corrections, send his sheet again, and again wait for an answer. This routine could take up months. And, possibly, it wasn’t such a bad thing that the communication was so slow. Today, many architectural issues are resolved too quickly. Part of the curators' work in a biennale pavilion: pfl 13 Lacaton & Vassal Architectes. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThe theme of the past is explored by the curators through installations that were executed by Ireland’s top architectural firms. The curators asked them to select their favorite projects out of the ones that were built from the break of the last century to the 1930’s and showcase the work of those architects through these installations, as if seeing them through the eyes of modern architects. Part of the curators' work in a biennale pavilion: freespace videos. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruAnd, although the subject of our conversation is the curators’ work, I cannot help but ask you about your opinion of the national pavilions. Which one did you like most of all, and why? I really liked the Nordic Countries Pavilion where Sweden, Norway, and Finland created a multilayered composition with a bio-organic theme that you cannot even read at first sight. Part of the curators' work in a biennale pavilion: "Meeting great buildings", fragment. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruThis is essentially correct approach to working with space, light, and air. And I just cannot help wondering how this all came about – there are lots of great architects in these three countries, how could they ever come to an agreement to share about a single theme? This approach – I would call it “humble” – is all about reserve, modesty, dignity. This humble approach also shows through in the work the curators of the biennale. The Nordic Countries Pavilion. Photograph: Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru |

|