|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 06.06.2018 | |

|

Anton Barklyansky: “To me, architecture begins with questions” |

|

|

Lilya Aronova |

|

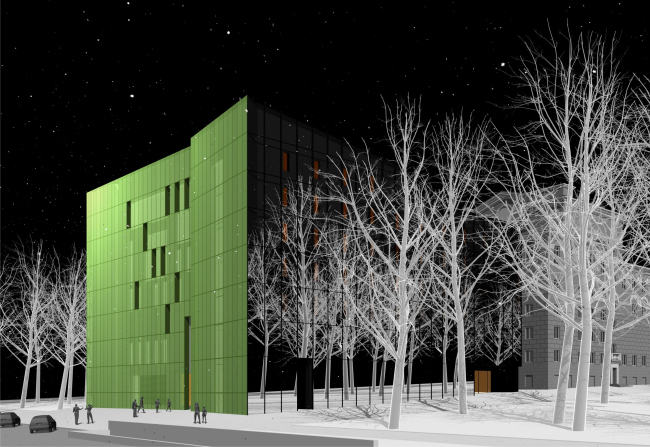

| Studio: | |

|

The leader of “Synchrotecture” speaks about the main architectural trends of the future, explains what the name of his company means to him, and why he does not like the term “architectural firm”.  Anton Barklyansky © SynchrotectureArchi.ru – How did you come to the idea of starting your own company? Anton Barklyansky: – To begin with, I wasn’t even planning on becoming an architect. I did not even suspect that there was so much room for creativity in architecture – in the city of Perm where I grew up most buildings are dull and bleak, designed for purely utilitarian purposes. What I really was into, however, was graphic design. I entered the Ekaterinburg Academy of Architecture and Fine Arts, where they taught the profession that was interesting to me, and, studying there, I discovered a hall of foreign literature with lots of magazines and books on architecture. It was then that I discovered the profession for myself, and realized that you could do amazing things in it.  © SynchrotectureAfter I graduated I got back to my hometown and I worked in the studio of Victor Tarasenko for seven years. Everything was going fine but with time I developed a feeling that I maxed out: I realized that working for that company I would never be able to get the quality of architecture that we see in magazines, the clarity of design ideas that I always longed for. And I decided that I should also learn from foreign architects. This is why, after I moved to Moscow, I first worked for the British company “McAdam Architects”, and then at the firm of Erick van Egeraat. – So, what did this experience give to you? – It gave me a feeling of new prospects: I understood which way to go. I saw just how vastly different our approaches could be – foreign architects look at many things from quite a different perspective. Take the general concept, for example. In Perm, it was a meager twelve-page scrapbook: a master plan, a few main plans, and a few façades – and, well, that was it. And Egeraat prints pamphlets the size of a thick book that contain all kinds of information about the historical and town-planning context, the project’s interaction with its surroundings, its functional content, and, to cap it all, the analysis of the developed territory down to the pedestrian level. The Europeans invest their time into pre-project survey – because you need to have an understanding of how you will form the space, what it currently looks like, and many other things in order to come up with the right proposal for its future development. I think that the importance of this stage is grossly underestimated in this country. Because the accuracy of our solution when still in the concept stage defines the future of this place, this building, and the people who will live or work in it; it defines whether this place will develop further or die away by degrees. After Erick Van Egeraat, I worked for two years at Sergey Skuratov architects. This was a great school of perfectionism – how to search for and find the best possible solutions. At the same time, my hometown “would not let me go” – projects kept coming from over there, and they are still coming today – What projects were those? – For example, we developed a master plan for the campus of the local Polytechnic University. This territory has been used by the university since the 1960’s and the original master plan provided for separation of the functions: dormitories in one place, academic buildings in another, and laboratory buildings still in another… And all this was situated in a romantic pine tree forest. We proposed a solution how to tie in all of the functions into a single system and make this large chunk of land convenient for pedestrians. Also, instead of one multistory dormitory, we designed a few human-proportionate cottages standing amidst the trees, organizing a recreation area between them. Part of the campus with these student houses is already built.  The forest campus © SynchrotectureAlso, in Perm, we reconstructed the “communal kitchen” (a dated soviet term for a large-scale catering establishment – translator’s note), a historical building the 1920’s designed in the constructivist style. It was important to give the building its original look lost in the reconstruction in the 1970’s. We cleared the façade of the stained glass windows, returned the original windows with the characteristic divided glazing and other details. It was these projects that gave me a chance to start my own company in 2012. At first, it was just called “Anton Barklyansky Architectural Studio”. Later on, however, I came to a conclusion that my company must have a name of its own – this way, the people who work here will really feel as if they are part of something. And this is how my company got a name of SYNCHROTECTURE. – What does this name mean to you? – It is a combination of two words – “synchronization” and “architecture”. There are many issues that an architectural project is meant to solve. There are stakeholders of the project, and future users; there is a city, there is a developer, and the architect must take on the function of synchronizing all of their needs. In this case, you get an opportunity for getting an integrated project that will be valuable for its place and its users, one that will give momentum for the future development. – How is the working process organized in your firm? – In our case, a “firm” would probably be the wrong term because, to me, a “firm” is a place where everything is firmly defined by its Master, where everything is drawn by his hand or dictated by him. This is not the way it is in our company. Yes, I am a leader but still, we are a company. For every project, we form a workgroup, in which everyone is responsible for their specific segment, depending on their experience and/or inclinations. What we don’t have is any sort of hierarchy – the “chief architect”, the “senior architect”, the “junior architect”... What is more important for us is a dialogue when everyone gets their point across. I myself personally can be a member of the team in my own right, or I can watch it from the side, correct the results, and handle critical issues. – What do you usually start you work on a project with? From plans, volumes, maybe from façade sketches? – With questions. With numerous questions that we ask ourselves and our client – why this, why that, is this really important? Plans, volumes, and everything else is secondary – all of these things will spring naturally from the answers to the questions that you ask. So, the first thing that we do is we take multicolored stickers and write down all of the questions that we may have in our heads. Then we post the stickers on the wall and think of the priority for each of the questions. It is also very important to ask the right questions because the answers that you are going to get hugely depend on your questions in the first place.  © Synchrotecture– And how do you go about organizing your relationship with the client? – The perfect situation is when the client is involved in the design process. Because he is also responsible for the end result, and it’s important for him to know which solution comes from where! We try to organize regular workshops where we discuss the arising issues together. Not every client is ready for such type of work, of course. In this case, we get to do all of the pre-project survey ourselves. This includes going outdoors, watching the future construction site, asking around, and then we bring the results of such work to our client in the form of conclusions and recommendations. Because it is still important for him – if for no other reason, then because of the fact that creating the right atmosphere has a direct impact on the sales figures.  © Synchrotecture– You literally go outside and start asking around? – Yes, we do. It’s important to analyze the space that you get to handle, to see how people live, what they would like to see here, what they want to keep, and what they are missing right now. The task of the architect is to widen his perception focus, understand the potential that the place has, and get the fullest picture possible: what things will be appropriate here, both in terms of form and content. And to create, based on this knowledge, an environment that is comfortable and interesting to be in – and not from the point of view of the architect but from the point of view of the future residents! Such an approach, the way I see it, helps you to come up with something that’s interesting and unconventional, not just something that you could throw together offhand. While in the world practice the task of the architect is not just about calculating the budget and coming up with some sort of structure, but also understand how the building will function and how its future users will interact with it, we in this country are only moving in that direction. On the other hand, if you just go ahead and get down to drawing things without bothering to get any background information and without processing it, your drawings will inevitably come to standard patterns formed by your previous experience. This is just not the way new things are born. – Do you have any taboos in the profession? Something that you would never do? – Build in the styles of the past. I really enjoy designing in a historical context but you need to do it very delicately, and probably the worst thing you can do in this case is imitate your neighbors stylistically. A fake is always a fake, like a death mask, behind which there is no life. At the same time, I really enjoy being in places that are breathing with history. I remember my first trip to Europe when I at once found myself in the modern Dutch city of Almere – it was only built in the end of the XX century, and it was literally stuffed with modern architecture. In a few hours I literally fled from that place, so dull and monotonous visually and otherwise, to Utrecht, where the daring architecture of the XXI century peacefully coexists with buildings that are centuries old. And when they recreate buildings based on the “historical drawings”, they still look plastic. You need to learn to single out what is really historically valuable, and, doing new things, make them ostentatiously new, by contrast. This will bring out the best in your project, and the users will be also able to see – again, by contrast – how things were built in the days past. For example, when we were working on the concept of the new building of the French Lyceum in the Milyutinsky Alley, together with our French partners Agence d’Architecture A.Bechu, we at once agreed that the new volume would be light and transparent as opposed to the brick historical buildings, and this transparency would expose the main communication streams that unite the complex into a single whole.  The concept of expanding the French Alexander Dumas Lyceum in the Milyutinsky Alley © SYNCHROTECTURE in collaboration with Agence d’Architecture A.Bechu and SETEC Inginiring– So, you like contrasts, don’t you? – I guess you could say that. Contrast of shape, contrast of texture and color... Specifically, when we work with colors, we often employ the principle of contrast – the number of colors is minimal, these colors serving as a background for one single highlight. This principle is equally applicable to our landscaping design: the natural forms enhance the impression from the austere architectural object. When we were doing the housing complex ASTRA in Perm, we from the very start included into our project the contrast between the building and the landscape. While the building itself is pristine and rectangular on the plan, with a jagged roof, the yard was full of soft and natural curves of hills and trees, multiplied manifold in the stained glass windows. We hope that the residents will appreciate this idea... Another example is the concept of the National Center for Contemporary Art on the Khodynskoe Pole that was shortlisted for an international competition. In this project, the geometric outline of the building's main façade rests on soft landscape shapes, drawing it inside of the building.  National Center for Contemporary Art © Synchrotecture– What are you currently working on? – We are designing a house in the ZILART residential area. It will have an unusual façade of windows that are differently sized. It was devised as a natural pattern created by the elements. We want it to be visually intelligible and at the same time “flowing” at the expense of the absence of predictable repetition – as a rock pattern chiseled by the wind, or an animal’s skin.  The house in the ZILART housing complex © SynchrotectureThere are also a few projects in Perm: the building of the Mining University is being built, a mansion is being designed at a historical street, with an annex of an office complex. In that project, we are solving the task of creating a mix of functions, at the same time keeping the historical building and harmoniously connecting it to the new modern volume. Meaning – contrast again.  Reconctruction of the historical object and the construction of a new office building, Perm © Synchrotecture The project of widening the Mining University and linking two buildings with an overpass © Synchrotecture– What do you personally prefer – designing residential buildings or public ones? – Currently, I am more into public buildings. This is where many users come together to create this yarn ball of activities that you need to gently unwind. In addition, there is a greater freedom of form making in public buildings. This is not to say that you cannot design a residential building in an unconventional manner – the thing is that this form must grow from the inside, like a response to society’s need for “different housing”. This is how it happened back on the 1930’s, when new needs of people led to most interesting experiments in the field of form making. Had I lived in those days, I would have eagerly taken part in that process. – What do you enjoy most of all about your work? – I like it when we come up with some new scheme of organizing space that I never saw before. True, not every project poses a need for that but it does happen now and then that you are faced with a truly challenging task that involves a huge number of factors and limitations, and you just have to do some creative thinking in order to find a solution. How to create a space that would be both interesting and at the same time intuitively navigable, and how to combine – in one project – several functions, building a smart system which would not be perceived as a complicated one, separate all the streams and understand what is really important and what you could possibly do without. The way it was, for example, with the elite residential complex ASTRA in the center of Perm. Ultimately, we got a project that was unique for Perm, organized on the basis of the perimeter construction principle with a residents-only yard.  The elite ASTRA housing complex and the reconstruction of shopping arcades of the XIX century © Synchrotecture ASTRA housing complex © Synchrotecture– What else do you think makes your strong points as an architect? – Probably the fact that I always try to rethink every task that I have by looking at it from a different perspective. To propose a purer solution that may seem unconventional at first. My first mentor, Victor Tarasenko, once called me a stereotype breaker. This is probably what my whole life is about, really. Because I like being surprised, and I want this world to have more surprising things in it!  The concept of the building of the Perm academic theater of opera and ballet named after Peter Chaikovsky © Anton Barklyansky, Victor Tarasenko, Stanislav ShiryaevAlso, I think I’m good at catching on the world’s latest trends and incorporating them in my projects, which helps me come up with new things nobody saw before. When you see the directions, in which architecture develops, and use them now, this helps you to create spaces that will serve people for decades to come. This ability comes in very handy, by the way, because oftentimes a few years may elapse from the idea of the project to its implementation. And this is why it is particularly important to make sure at the very start that your solutions will not look obsolete in ten years’ time. I enjoy observing new trends and incorporating them into my work, and often it just happens intuitively. – Then I think that my next logical question will be – how do you see the architecture of the future? – An obvious trend that is gaining more and more momentum today is energy efficient design. For example, when we were working on the competition proposal for the central hub of the district of Ryde in Sydney, there was a strict condition – all of the solutions were to comply with the LEED Platinum standard. It is virtually a norm for Australia. Such approach is, regretfully, not relevant for the Russian reality.  Concept of the central hub of the district of Ryde in Sidney - a multifunctional administrative center © SynchrotectureAs far as longer perspectives are concerned, the first trend is that architecture is less and less “steel and concrete”. As early as today we see buildings out there that are “alive” – they adapt to weather conditions, climate, and even the change of night and day. Another trend is the urge to put us as human beings back to our natural habitat that we all but lost with the growth of megalopolises. The most vivid proof of that is the fact that today they design more and more projects with huge amounts of greenery on the façades; more living plants are appearing inside the buildings – for instance, the airport of Singapore is full of full-size trees. This we create an environment that is comfortable for us as humans to live in. A third trend is the total digitalization. As early as in the nearest future, sensors installed into the technological system of the building will gather information about its users and about their preferences, giving a quick-response feedback, thanks to which the house will “learn” to fine-tune, say, the power consumption plan, some other functions, and, possibly, even the color of its walls, should such need arise – suppose, the house “understands” that its residents don’t like its original color. Possibly, thanks to this feature, we will be learning new things about ourselves. As a consequence, the approach to designing buildings will also be changing because you will be able to automatically process and take into account the whole pool of gathered information. An architect will become a little bit of a software developer who writes codes – an architect that ultimately designs a lifestyle. – Is there something that unites all of your projects? – In spite of the fact that an architect in the course of his career solves a great number of different tasks, we always try to make our end result as simple as possible. The last thing that I ever want to is chaos: everything must be loud and clear, though not necessarily linear. Probably, you might say that this is the common denominator of all of our projects – the inner co-subjugation that hides behind the outward simplicity. |

|