|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 25.09.2017 | |

|

Mental Image |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Levon Ayrapetov | |

| Valeria Preobrazhenskaya | |

| Studio: | |

| TOTEMENT/PAPER | |

|

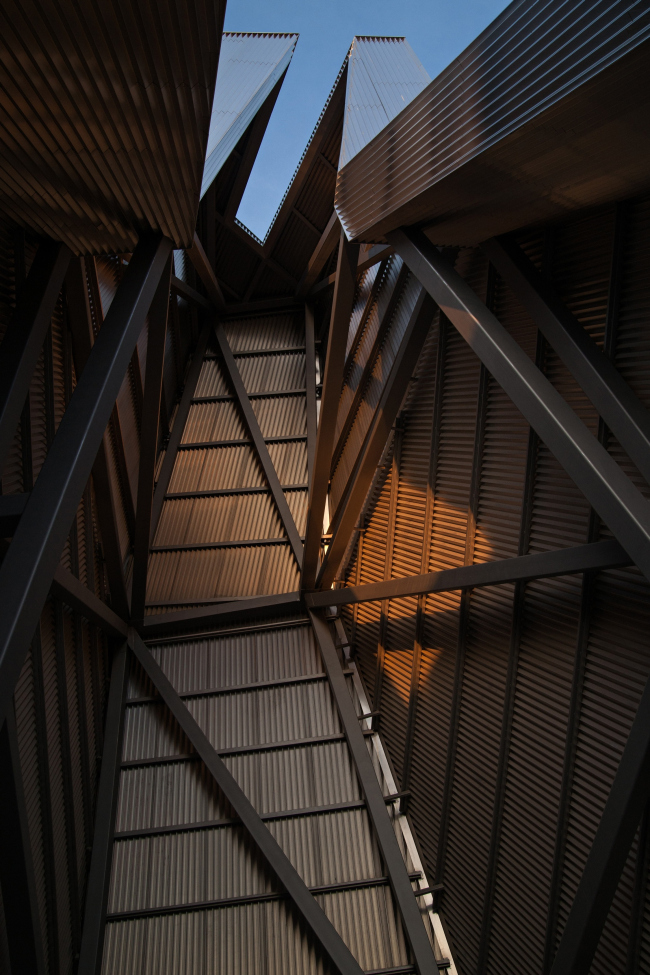

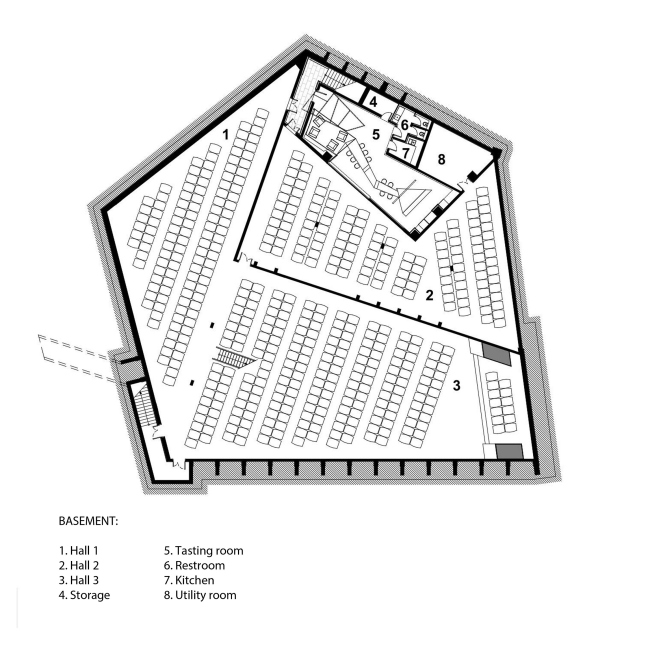

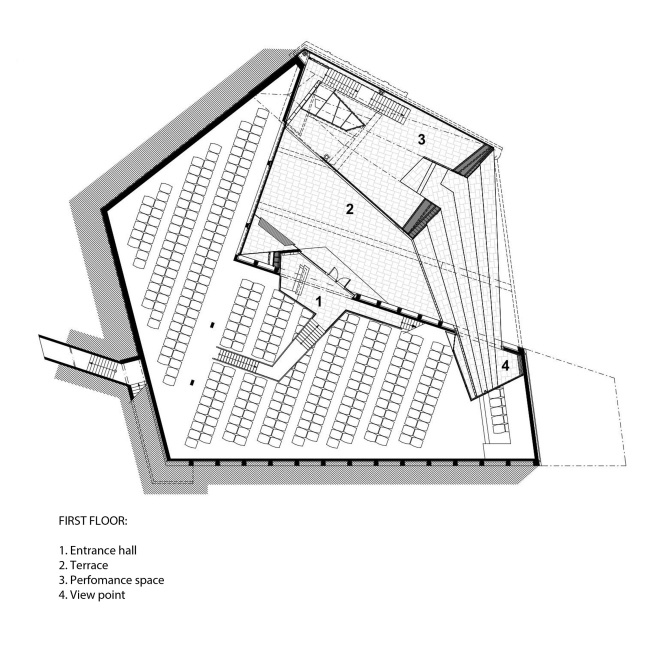

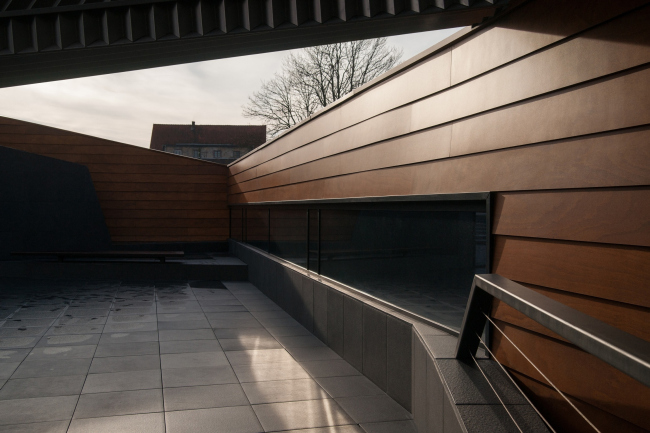

In the context of Russian architecture, the building of repository museum of cognac in the city of Chernyakhovsk is a rare example of a situation when the building’s obliging function and the architects’ creative thinking do not conflict with each other but work together to create well-thought and well-balanced architecture, interesting to all human senses. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovWe wrote about the building of repository museum of the cognac house “Alliance-1892” in Chernyakhovsk back in 2011, when it was still in the design stage. Today, the project has been implemented virtually with zero deviation from its original design; this summer it was shortlisted by WAF-2017. I don’t think I will be mistaken if I say that for Levon Airapetov and Victoria Preobrazhenskaya this building is now one of their favorite architectural projects – thought out to the last detail and implemented exactly the way the architects wanted to see it. Cognac Casks in Room 3 of the repository. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovThe city of Chernyakhovsk (the former Prussian Insterburg) is a small city that did not grow much larger during the soviet times. The cognac house is situated almost in the center, or, rather, a little south of the border of the city’s historical center, immediately behind the railroad line leading to the main city terminal. This is convenient: the railroad delivers to the distillery a French spirit to be treated in accordance with the French technology. The alcohol is then poured into oak casks and matured in them for the appropriate period of time – during this time the spirit loses its strength and takes on the desired taste, then it gets blended and ultimately bottled. The building of the distillery itself is situated closer to the railroad line; it is essentially a large, almost square, hangar of a light brown color, sporting a neat yet still industrial look. Project. Birds-eye view. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERQuite different is the cask storage building designed by the architects of TOTEMENT. It is situated a little further away from the railroad track, before the main and only entrance to the factory premises, immediately after the checkpoint: it meets everyone who comes in here and at the same time signifies the presence of “Alliance-1892” in the green semi-urban space that the southern part of the former Insterburg presents. It is simply impossible to overlook it – the architects say that, in spite of the fact that he personally approved all the project draughts, the director of the distillery was somewhat surprised when he saw the actual result; the locals have made it their pet sport coming up with names for the unusual building. Surrounded by three-story houses with tall hipped roofs, the repository museum looks indeed unusual yet, at the same time, very European: I would even go as far as to say that such an iconic building would be quite a regular thing if it stood at the edge of the historical center of any small German town. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovNext to the repository museum, there is a checkpoint through which people enter the distillery; it echoes the two towers but it is smaller and more reserved, combining achromatic black and gray. Checkpoint on the left. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovChernyakhovsk, regretfully, is not exactly a rich town, and currently it looks rather shabby. The territory of the plant stands out against this territory with its neatness, while the distillery that provides jobs for many of the townspeople has a well-coordinated production cycle. The fact that its territory got a high-profile “compensation” building is quite a logic step in the distillery’s development. All the more so, because, as the “masters of cognac” (not a figure of speech, there is indeed such a specialty) explain, the casks, in which the noble spirit is matured, are very sensitive to the surrounding atmosphere, i.e. they are also “living beings”. But then again, all the masters of culinary arts claim something in these lines… Sketch. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERBesides the artistic legends of the “living” spirit, whose quality is affected by absolutely everything, cask storage is indeed subject to a whole range of rigorous rules. One of them is that the room must be constantly aired because the oak casks breathe letting out alcohol vapors. The spirit inside gradually loses its strength, while the air gets saturated with these vapors and even becomes explosive. So at this point we will at once share about one of the architects’ ingenious findings – they were able to avoid the necessity to create a complex and expensive ventilation system by calculating the vectors of the air flows: the top part of the repository has outlet ventilation installed in it; in the bottom part, there are inward draught grilles. This way, the ventilation expenses were cut down almost by a hundred times. Besides, the building is not heated: the repository itself is sunken into the ground, and its temperature is relatively stable, about 10 degrees Centigrade, with minor seasonal differences. Image However, no matter how much you speak about pragmatic things – and each function, be that storing and maturing the spirits or showcasing them, has its own pragmatic requirements – still the main thing about the building that the architects ultimately got is its image and its form. Small and production-oriented as it may be, this is still a museum, and the architects approached it the way they should approach the task of designing a public building: they filled it with plastique and associations. This building is acutely associative – although far from literal, all the allusions are well and many times thought out and expressed by the architects in words, drawings, models and sculptures. “We can say now that this thing signifies this and that but it would be interesting to show it to different people and ask what they see” – critically meditates Levon Airapetov. A drone video of flying over the complete museum building Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovBut then again, the main idea of the project is hard to disagree with: above the earth we see two volumes: one, broad and made of wood, crowns the sunken-in storage room, and looks like a woman, calm, and looking pregnant with all the casks it contains. The other volume – a glittering metallic tower with a cut-through – is installed above the glass ceiling of the museum’s tasting room. “This is a “man”; he runs around, he hunts for the mammoth, and he protects the woman from everything – says Levon Airapetov – But it’s also sort of broken, though tall, still empty inside. He cocked his head wondering what to do next”. When, in order to elaborate on the façades, the architects made their development drawings, it turned out that the two towers looked like two origami figures, male and female. Which brings us to the Chinese concept of Yin and Yang, the sign that describes how seemingly opposite or contrary forces may actually be complementary, interconnected, and interdependent in the natural world, and how they may give rise to each other as they interrelate to one another. Development drawings of the facades. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERSlanted at different angles, the two towers indeed look like generalized silhouettes of male and female figures. Devoid of any podiums, they look as if they shoot up through the ground, together but apart, similar yet contrastive. As if they are quietly speaking to each other in a unique language of their own – the way a husband and wife could speak to each other, using words that only two of them know and almost inaudibly, stealing a sneaky glance around from time to time. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovRepository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovThe hollow-bodied metallic stela glitters with its metal covered in zigzag grooves – it generally looks like a blade. The sheets of the outer covering are mounted on metallic framework, completely opened and not masked in any way on the inside. It is likely that in the future they will project to the framework some sort of moving pictures like birds or clouds. The broad opening of the entrance looks like a mountain cleavage: as if the metallic wall split in two or simply parted opening a gateway to somewhere that no man could walk – because once you step inside you see the insides of the metal structures. One can see here a metaphor of a production facility that has been open to the public eye. But then again, no matter how “hollow” the metallic tower might be, it is still the centerpiece, the main entrance, and the portal of its kind. Inside the tower, there is a glass floor that reveals an underground tasting room, which this way gets a certain share of ambient light and an eccentric ceiling. They even discussed an idea of going even further and replacing the glass ceiling with a swimming pool so as the rays of sunlight would get inside, refracting through the water, but ultimately the architects opted out of it. Upward view from the tasting room. Through the glass floor, one can see the metallic tower, below - the plan of the building scratched in wet concrete. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovMetallic tower on the inside. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovView of the metallic tower from the inside out. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovThe glass floor of the metallic tower. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovRepository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovThe second volume is semi-reclining, going underground with the “womb” of the repository: on the west side, it forms a small hill, as if the building had fidgeted around a little making itself comfortable under the ground duvet. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovThe walls of the repository are brutalist concrete, with traces of decking; the ceiling, on the other hand, is made of light metallic girders. The casks lie on the shelves not in a symmetrical array but in a slightly staggered fashion, and the architects liken them to a clutch of eggs. The “clutch” is lighted by lamps: these are safe LED’s but they are executed in the form of traditional old-fashioned bulbs; they are also suspended from the ceiling on cords of different length. In the glittering lights, the architects see allusions to the autumn grape harvest festival: “when they tread out the juice from the grapes, they sing, play music, and usually this happens in the evening, candles glow, and fireflies swirl around them”. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovThere are no openings in the “female” building but it has panoramic windows and a “head” – the upper part of the volume looks upon those who enter the territory with a wide embrasure as if checking them for ID’s. Behind this big “eye”, there is a “tail” that makes a sharp turn upwards and looks up into the sky with a panoramic window of the same kind; this way, standing on the ground below, one can see peek-a-boo people on the balcony and the sky beyond. In the old times, such turrets were called watchtowers. Besides its doubtless likeness to an animate creature, the wooden tower also looks like a metaphor of a wooden cask: its walls are covered with 3-millimeter veneer sheet of a mahogany color. One should hardly mention the fact that the wooden panels are horizontal, while the metallic detailing of the neighboring tower is vertical: they have nothing in common yet there is no doubt that they are kin to each other. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovMuseum For modern breweries and distilleries, showcasing their production cycle is basically a fashionable trend of today: the clients, partners, and vendors must be impressed not only with coordination but also with artistry of production. And, in order to achieve this, you need to organize demonstration and tasting that work together to create an image and a legend. This is why, although it stands on an employee-only territory, this repository is a museum open to pre-organized guided tours and in-company events. On the other hand, it is a museum, a place of presentation, meditation, and showcasing the production to its best romantic advantage. This is why an important part of the building is its viewing balconies and platforms. The museum has specifics of its own: its entire exposition consists essentially of stacks of casks and a tasting room; therefore, the building itself turned into a showcase, and instrument of meditation and contemplation considering of a string of perception points. It’s not like they let you in and allow you to walk around as you please – the architects stay and dose the impressions, gradually uncovering the nuances of the subject matter. This process is akin to enjoying a glass of cognac, yet more abstract and meditative. As for Yin and Yang, the authors mention them for a reason. Speaking about the two different volumes, one can think that they exist independently – but this is not the case. Contrastive yet cast in the same mold, the towers stand on one common pentagon podium that, when viewed from above, looks a bit like a slightly skewed but still recognizable Soviet quality sign: “Yes, of course, we saw this. We had no deliberate intention to draw this sign but we are quite happy that it turned out this way” – says Levon Airapetov. Between the two volumes, there is a small yard accessed by slightly sloping stairs that are “strung” like power lines, between the entrance to the “male” tower, and the sunken-in cantilevered entrance to the “female” one. The lines of the stairs are tied in a “knot” and it may seem that the host of strings issuing from the metallic tower “made a hole” in the opposite wall, thus closing the contour of the building. The cantilever that "intrudes" the space of the repository from the outside; Room 3. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovView fro the yard: stairs and the window, through which one can look inside the repository. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovBalcony of the "head" of the wooden tower. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovAt the same time, this place gets its first outside viewing route. Even before entering the yard, moving along, and not across the stairs, we can see both the tasting room (through the window in the floor of the metallic tower) and the repository (through the window on the left) – it shimmers with festive fireflies of the repository’s bulbs, and at once an impression is created that it’s fun and that something good is afoot inside. Then the route splits in two. Inside the yard one will see the largest entrance to the repository, while in the far corner of the metallic tower one can get down to the “museum” space of the tasting room. Beneath the yard, there is yet another repository hall of a smaller size, the windows of the tasting room showing its casks that harmoniously complement the display of the bottles on the wall. The tasting room is situated on a level with the repository, and, getting outside of it, one can pass the second hall and get into the third, towards the stairway of the first entrance which connects most of the viewing platforms. The stairway stretches along the north wall inside the wooden tower from the repository’s wall towards the entrance, and then higher up it forms the balcony above the viewing cantilevered structure – the one that intrudes into the space of the repository and through which one can peek inside. Then the stairway leads to the head of the wooden tower one can walk out onto the upper balcony that overlooks both the entrance road and the upper stained glass. The silhouettes of people standing here are quite viewable from the ground. Plan of the underground level: rooms of the repository and the tasting room. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERPlan at the zero mark. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERTasting room; on the right behind the glass one can see casks in Repository 2, situated underneath the inside yard. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERHall 3 (the largest one), without casks yet. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovYard. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovYard and the entrance to the repository. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house. Photograph © Gleb LeonovAs we can see, the viewing route can be easily divided into several fragments; but if one walks the whole of it, his way spins like some voluminous spiral, “screws” into space, and becomes its conceptual axis – so one may even suspect that the seemingly sophisticated movement of the volumes is strung upon the main space spiral of the route of the guided tour, is motivated by it, and, hence, is integral inside. This immanent motivation is yet another important narrative of the building, possibly its conceptual nucleus, and not just a “literary” story of a dialogue between man and woman. At first sight it may seem that the architecture of the repository museum is conditioned by the search for an effective gesture but this is not exactly the case or, rather, not the case at all. One can only get the right understanding of it if he knows that the powerful energy of the form that is undoubtedly present here is strictly conditioned and limited by the context, the function, and the form of the land site. Levon Airapetov and Valeria Preobrazhenskaya speak about the key points that they find in the process of doing the pre-design survey; then, connecting the dots they come up with the form that is conditioned by the circumstances – and then this form can be creatively thought out and “animated”. However, each line and surface remains motivated, and not arbitrary. Besides, this form is not as complex as it may originally seem to be: it becomes complex in the process of arranging the volumes in respect to one another and opening up the viewing angles but in actuality – as Valeria Preobrazhenskaya explains – two walls of each of the volumes are parallel, i.e. the form itself is rather, even necessarily, simple. And I want to add at this point: just in our life, everything that’s complicated arises from interaction of simple things. The important poits (or "dots") that constitute the basis of the project. Repository museum of "Alliance-1892" cognac house © TOTEMENT / PAPERThe grid of the lines that connect the important dots is the basis of the building, its speculative plan. The architects once even showed this grid at one of their exhibitions; then they “scratched” it through wet concrete on the wall of the tasting room – as a reminder about these meditations that gave birth to a concrete form. This sign looks like a symbol of some archaic deity which is quite appropriate in this case: what else can this repository museum be other than a temple of the god of wine, or, rather, gods of wine who are embodied, to some extent, in the towers shooting up from underground? Then this animation of form (which is very strong in this project) starts to make perfect sense: to semi-abstract creatures literally grow from the cognac vapor becoming the embodiment of both sophisticated production cycle and the architectural meditation about it, concentrated and agile, yet run through the filter of necessity. It’s been about a decade now since the architects started searching for architecture outside of shape: in ecology, economy, statistic, function, and landscaping. Given this background, what TOTEMENT did is a very brave thing to do, even though they did nothing more than find a motivated shape – the kind that arouses emotions, opening up the spectator’s vision, but the kind that is definitely far from excessive. After all, this is what architecture should be about – give shape to the interaction between the human senses and the space. But today those who explore this theme are few and far between – maybe because the task is so challenging. |

|