|

The text for the catalogue of Russian pavilion of XI architectural biennial in Venice

Two thirds of the history of Russian architecture is written in Latin characters.

The Uspensky and Arkhangelsky cathedrals, Ivan the Great, Spasskaya Tower, the Church of Ascension in Kolomenskoe, the Church of Pokrov na Nerli, the Peter and Paul Fortress, the Alexander Column, St Isaac’s and Smol’ny cathedrals, Tsarskoe Selo and Pavlovsk, the Hermitage and the arch of the General Staff Building, the Krasnoe Znamya Factory, the Tsentrosoyuz building…

All this was built by foreign architects.

Over the last 15 years no fewer than 50 foreign architects have designed buildings in Russia.

And yet nothing of this has been built.

Let’s be exact: foreign architects did, of course, have some things built during the 1990s. Or, at the very least, they played an active part in the process. But when you begin to list these collaborative efforts, you feel a certain discrepancy with the list with which we began.

The International Bank on Prechistenskaya naberezhnaya, Unikombank in Daev pereulok, Sovmortrans in Rakhmanovsky pereulok, Park Place on Leninsky prospekt, Sberbank on ulitsa Vavilova, the office buildings on ulitsa Shchelkina and Trubnaya ulitsa, Smolensky passazh, the Zenit Business Centre on prospekt Vernadskogo, the Sberbank building on Andron’evskaya ploshchad’, and a single proper ‘imported’ structure – the British Embassy on Smolenskaya naberezhnaya.

All these are buildings of high quality, at least as seen against the general background, and this quality was largely a result of the involvement of foreign builders such as Skanska, ENKA, and Ove Arup, companies which had been present in Russia since the mid 1980s. But there has been no architectural breakthrough. Private clients are not yet powerful enough, and the authorities have had no great interest in modern architecture. The ‘Law on Architectural Activity’ passed in 1995 takes an apparently humane approach to regulating the activities of foreigners: “Foreign citizens… may take part in architectural activity on the territory of the Russian Federation only together with an architect who is a citizen of the Russian Federation… and possesses a license.” But compliance with this law has required obtaining so many approvals that the importance of the local architect has begun to prevail and at times nothing has survived of the work of the foreign architect. As a result, all the above buildings bear the mark of severe compromise, regardless of the big names, including William Alsop and Ricardo Bofill, which stand behind them… But these were early days.

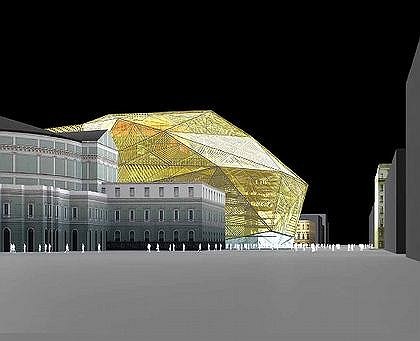

The trend began to take off at the turn of the century, and the first real fruit of the process was the story with Eric Owen Moss. In 2001 this Californian Deconstructivist designed a new building for the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. The extravagant look of the building prompted a huge public outcry, and the fact that Moss had been called in to design as a friend, without any competition being held, led to serious concern among the architectural community. The project was killed, but the authorities promised to hold the first international competition in the history of Russia.

In spring 2002 a firm called Mercury invited Jacques Herzog and Pierre Meuron to design Luxury Village at Barvikha [outside Moscow]. A sketch was made, but the client was not pleased with it. In the end, Luxury Village was designed by Yury Grigoryan.

In autumn 2002 a competition was held to design the City Hall and Moscow City Parliament building at Moscow City. World stars such as Alsop, Moss, Bofill, von Gerkan, Schneider and Schumacher, and Neutelings and Riedijk took part. Victory went to Mikhail Khazanov.

Spring 2003 saw the competition to design the second stage for the Mariinsky. Participants included Hans Hollein, Mario Botta, Arata Isozaki, Eric Owen Moss, Erick van Egeraat, and Dominique Perrault. The latter won, but the design was compressed and then taken out of Perrault’s hands. Perrault renounced his authorship.

In autumn 2003 a PR campaign was launched for Russian Avant-garde, a project by Erick van Egeraat. There was a lot of muttering from Russian architects. Aleksey Vorontsov detected plagiarism in van Egeraat’s design. Nevertheless, the project steamed ahead towards planning permission – and then unexpectedly received a biff over the head at a session of the Public Council for Architecture and Urban Planning, with the Mayor of Moscow declaring that it was a good design but precisely for this reason needed a more worthy location.

In spring 2004 it became known that Zaha Hadid was designing a residential building on Zhivopisnaya ulitsa for Capital Group. A poor-quality picture resembling a secret symbol did the rounds of the Internet, appeared in the same form at Arch Moskva, and then the project stalled.

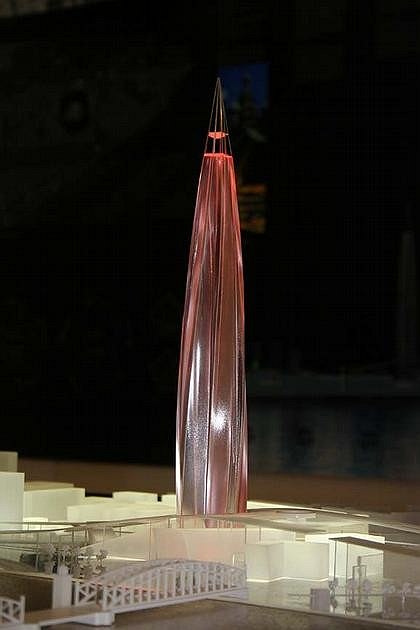

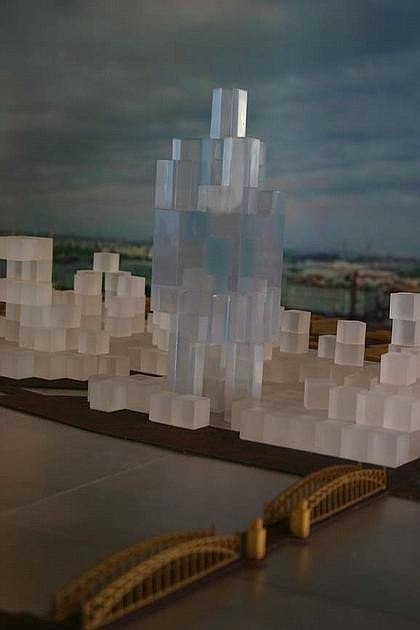

Finally, in summer 2004 Norman Foster visited Moscow and was treated by the general public as an ‘architectural star’. His lecture was packed, there were queues to get in to see his exhibition at the Pushkin Museum, there were countless interviews… His design for the Russia Tower at Moscow City was even approved, but so many additional co-authors from Moscow were involved in the design process that the result is muddled. Foster’s winning project for the reconstruction of New Holland in St Petersburg provoked a storm of protests and then came to a standstill. His design for a hotel complex on the site of the Hotel Rossiya did not appeal to the Mayor of Moscow, was sent back to be reworked, and then it emerged that the contest for the contract to demolish the Rossiya had itself been illegal.

This is an endless list of martyrs, so we’ll interrupt it here. One might, of course, say that seven years is hardly a significant period. However, Berlin needed only ten years to become an architectural capital, and Dominique Perrault sorrowfully notes that during the five years that the saga with the Mariinsky Theatre has been going on, he has managed to build the university at Seoul, a project which is just as complex and on a rather larger scale.

If the history of the presence of foreign architects in Russia is gloomy, the structure of these failures is amazingly diverse. An architectural design by a foreigner may be demolished (the USA Embassy), built and then abandoned (the Zenit Business Centre), cancelled (Meinhard von Gerkan’s project for Moscow City), handed to someone else (Erick van Egeraat’s City of Capitals; Legend of Tsvetnoy by Stefan and Günter Behnisch), transferred to another location (Erick van Egeraat’s Russian Avant-garde), declared illegal (Norman Foster’s reconstruction project for Zaryad’e), built after fundamental changes (Kisho Kurokawa’s Zenit Stadium), or may simply move forward with great difficulty (Norman Foster’s Russia Tower, Zaha Hadid’s office building on Sharikoposhipnikovaya ulitsa)…

However, when we analyze the problems which have obstructed the progress of all these projects, we unexpectedly discover their presence in the history of the buildings I listed at the beginning of this article.

The clients for the Mariinsky and the City of Capitals take the view that the constructional solutions proposed by the architects are difficult to carry out and dangerous. In 1830 the Council for the Construction of St Isaac’s Cathedral came to the conclusion that the innovative proposal made by the Frenchman Auguste Montferrand to place the cathedral on a rostwerk (a continuous foundation plate on a base of piles) was ‘harmful and perhaps even dangerous’. Furthermore, the council had doubts about the feasibility of creating a portico from monolithic columns. A year earlier, the Italian Carlo Rossi decided to employ iron beams in his Aleksandrinsky Theatre building. A fearful expert wrote a report to the Tsar and construction was halted. Offended, Rossi responded: “In the event that a misfortune of any kind should result from the construction of a metal roof, may I immediately be hanged from one of the rafters”!

Dominique Perrault is accused of inflating the estimated cost of building the Mariinsky’s new stage. In 1820 his fellow-countryman Montferrand was stripped of the authority to dispose of the construction budget for St Isaac’s, accused of pocketing the fees for painting work, and was the subject of hints that he had a personal interest in the choice of contractor responsible for dismantling the church that previously stood on the site of the new building. In 1784 Yekaterina Dashkova ‘bargained’ with Quarenghi, in the belief that the latter was creating too many decorations for the façade of the Academy of Science. Quarenghi fought back: “A platband is definitely necessary since it suits the larger scale and will embellish and improve the appearance of the building, which Her Excellency wishes to make in the simplest manner”….

Capital Group found Erick van Egeraat’s design for City of Capitals disappointing and gave the job to the American architects NBBJ instead. But, given that advertising for this project had already been published, the company insisted that a resemblance to van Egeraat’s design be retained and continued to use his sketches. Van Egeraat took Capital Group to court and won. In 1784 Giacomo Quarenghi began building the Stock Exchange on the Spit of Vasilievsky Island. And even got as far as raising the walls to the height of the cornice. But in 1804 Emperor Paul took a dislike to the design and handed over the project to ‘adroit’ (to use the description given by art critic Igor’ Grabar’) Thomas de Tomon, who proceeded to build one of the symbols of St Petersburg. Quarenghi hated de Tomon until his dying day.

Italian Mario Botta had been designing the Swiss Cultural Centre in St Petersburg. The city’s Urban-planning Council declared that his project ‘does not match the spirit of the city’ and decided to move it somewhere else. They moved it hither and thither, and in the end pushed it out to a location beyond Okhta – after which the investor, naturally enough, lost all interest in the project. In 1719 Botta’s fellow-countryman Domenico Trezzini built a palace for Prince Cherkassky on the Spit of Vasilievsky Island. Seven years later, the Emperor gave the command to ‘dismantle the palace to improve the look and space of the square and to use the stone and bricks in the construction of Audience and Senate Chambers”…

In her design for an office building on Sharikopodshipnikovaya ulitsa in Moscow Zaha Hadid made use of large horizontal areas of roofing. This would have been an eye-catching feature that would have allowed employees to step out of their offices onto a terrace. But Moscow is a city with snow, and it was not clear how the snow would have been removed from the terrace. So the design had to be changed. But the architects’ contract specified that the client would have to pay for any changes to the design. The project stalled. In 1928, especially for conditions in Moscow, Le Corbusier developed a system of ‘correct breathing’ – ventilation and heating to be installed between panes of glazing at the Tsentrosoyuz building. But this particular feature was never realized, and, as a result, the building suffers from appalling heat and terrible cold. But at least the project was built…

As we can see, all these problems did not prevent foreigners from adding to the glory of Russian architecture. Furthermore, all the key events in Russian architecture – Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, and Classicism – are connected with foreign architects coming to this country.

But it’s here that we hit upon a fundamental difference. Peter I and Catherine II invited foreign architects to Russia to get things built. They had a genuine interest in modernizing the country – in making it more civilized and European.

New-Russian clients call upon foreign architects for entirely different reasons.

The first evidence of this is the strange way in which competitions are organized. It might seem that a competition is a convenient and finely tuned way of ending up with an original architectural design. But it is also expensive and so undesirable. Competitions, of course, do happen. But even when the organizers set out with the best intentions, the result is ‘just as usual’. Examples are the competitions for the Mariinsky, the Gazprom building, Strel’na…

Another sign of the odd character of commissions given to foreign architects is that the genuinely fresh Western architecture which is so insistently promoted in Russia by Bart Goldhoorn (publisher of Project Russia and permanent curator of Arch Moscow) is completely unsuccessful here. The apparent reason for this is that its progressiveness is a matter of its restraint, appropriateness, simplicity, purity, rationality, and other Protestant values. Values which in Russia, of course, are not held in high esteem. Finally, and, it seems, most importantly, this architecture has insufficient ‘star’ quality. It’s not foreigners so much as stars that today’s Russian clients are keen to hire. In the past, however, foreign architects (with the exception of Schlüter and Le Blond) were not stars back in their own countries. In fact, in some cases they weren’t even architects! Cameron and Quarenghi were well known only as draftsmen; Trezzini as a master of fortifications; Halloway as a clockmaker; Chaffin as an explorer of mineral deposits... And it was only when they came to Russia that they became what we would now call ‘stars’.

All in all, you get the firm impression that the PR which springs up around all these stories is all that the clients need – that all this is merely a matter of the desire to cut a ‘flash’ figure. However, ‘flash’ is by no means an unimportant factor as an engine of progress in Russia. Forgetting for a moment the client’s ambitions, one may suppose that even the very fact of the arrival of modern stars in Russia will become an important landmark in the development of Russian architecture. In the final analysis, even such inexpressive buildings as the Cosmos Hotel and the International Trade Centre – built in the 1980s with the involvement of foreigners – were, when seen against the background of all the other grey architecture, such a breath of fresh air that people almost stopped breathing.

“Foreign architects can get away with more,” says architect Nikolay Lyutomsky, who has worked alongside foreigners in designing Park Place and the Zenit Business Centre and who is currently working with Zaha Hadid. “‘Look, I’ll create a restaurant in the Greek Room at the Pushkin Museum!’ Norman Foster will say, and suddenly this will turn out indeed to be possible. Which is to say that there is a sense in which foreign architects pave the way for us; they create a precedent.”

It is interesting to look at the way in which society’s reaction to this invasion has evolved.

The first large project (Moss’s design for the Mariinsky) met with an ambivalent response from professional architects. There was unanimous indignation at the behind-the-scenes way in which Moss had been chosen, but at the same time there was equally unanimous acceptance of the design itself; there was a feeling that “Russia has a catastrophic shortage of radical architecture” (Yevgeny Ass), that “it’s absolutely necessary to build something new in St Petersburg, otherwise the city will die” (Boris Bernaskoni), that “this is a brilliant provocation which is very much needed in order to stir up the stagnant bog of our architecture” (Mikhail Khazanov), and that “we absolutely need the presence of such people and things in order to raise standards” (Nikolay Lyzlov).

So, to begin with, Russia had great hopes of the West. People believed that foreigners would get our architecture moving in a forwards direction, set new standards, and create competition, without which there can be no development. But then, as time went on, and as people saw what was actually happening, disappointment set in. And this disappointment was as acute as their earlier hopes had been strong.

It turns out that star architects do shoddy work, don’t make the effort to understand local nuances of climate and psychology, ignore historical context, and regard our country as third-world, a place where it’s possible to get rid of a product that’s past its ‘sell by’ date, and a source of lucre. A further factor is, of course, the self-evident fact that the stars are becoming genuine rivals of local Russian architects. But the latter’s irritation is also quite comprehensible; it would be all right if the stars shone like proper stars, but…

It’s not only within the architectural profession that the attitude to foreign stars is changing. Even the press, which so joyfully promoted foreign stars all through the early years of the century, is cooling towards them. A certain architecture magazine now has a column entitled ‘Star under the microscope’ in which Russian architects gleefully explode the myths that have grown up around their Western colleagues…

Catherine II wrote, “We have French people, who… build rubbishy houses that are unfit both on the inside and on the outside, and all because they know too much.”

But we can agree that this situation in which stars are initially expected to produce miracles and then shown the door accompanied by jeers has largely been provoked by the clients.

It is not the stars who draw up a brief stipulating that a 400-metre skyscraper can be plonked down behind Smol’ny Cathedral or that the mystical island of New Holland can be turned into a cheap amusement.

It is not the stars who demolish the Frunzensky Department Store and the Palace of Culture of the First Five-year Plan.

It is not the stars who invite only foreigners to take part in a competition (as was the case with the Gazprom skyscraper), nor is it they who hold a parallel competition in addition to one that has already taken place (as was the case with the congress centre at Strel’na).

It’s not the stars who fail to give thought to how their extremely complex buildings will be used and maintained; it’s the client who does not take account of this.

It was not Montferrand, but Nicholas I who proposed gilding the sculptures on the frontons of St Isaac’s Cathedral…

When you compare the events of the last three years (all projects in St Petersburg are on the move; in Moscow they all grind to a halt), you could say that Moscow, unlike Petersburg, shows more pride in its attitude to the stars. But then it’s not clear why we need these stars at all. If we’re not ready to play the game called ‘modern architecture’, then what’s the point of puffing out our chests? Of compromising this game and thus setting ourselves up all the time? And if we are ready to play the game, then we should make the rules clearer (no skyscrapers in Petersburg!) and not place the stars in a stupid position.

After all, what are stars? They do what is expected of them. That’s the cross they have to carry. They are no longer their own men and women; they’re a brand. Which is why in the competition to design the Gazprom skyscraper Libeskind’s design was again all crooked, Nouvel’s transparent, and Herzog and de Meuron’s twisted like a braid… It’s not the stars that are regrettable, but the fact that they, in their starry sky, have this image of Russia as a place where people have discovered that architecture is cool and are ready to pay ridiculous sums for brand names.

One may, though, suppose (as Grigory Revzin has wittily done) that the stars fill the gap left by the abstracted design work which was a feature of Russian architecture during the heyday of ‘paper architecture’. Today our architects have more real commissions than they can handle; they just don’t have time for abstract design, but they remain nostalgic for that dream! And it’s this dream which is fulfilled by foreign architects with their stubbornly unrealizable projects. It’s another matter that the Russian dreamers of the 80s were entirely free to do what they wanted when creating their castles of paper: the brief was unambiguously utopian and it was this that made the result was so dreamlike. Today’s foreigners, on the other hand, honestly try to square up to the local reality; all the time, they’re trying to please, revolving matryoshki in their heads – which is why their designs so rarely meet with a positive response. But then think of Charles Cameron, who built the Agate Rooms for Catherine II only to find that the latter was not happy with this masterpiece and miracle: “It is strange that this whole building has been built for bathing in, but the bathhouse has turned out so poor that you can’t even wash yourself in it!”

But even while the ‘boom in stars’ remains a ‘paper’ one, there are some buildings designed by foreigners actually being built. Sergei Tchoban, who may provisionally be described as a foreign architect, is completing the Federation Tower at Moscow City. Frenchman Jean-Michel Wilmotte, whose design for a new embankment in Volgograd (2004) was never actually built, is finishing a business centre for Krost on prospekt Mira in Moscow. Ulrich Tilmans of Germany is designing Villanzh, one of the residential blocks at Krost’s Velton Park. In Yekaterinburg the foundations have been laid for Iset’ Tower, designed by French architects Valode & Pistre. In Astana Norman Foster has actually built his pyramid.

But what do we see? That it’s not stars who are building, but third-rate architects. That they’re building not in Moscow, but in other cities. That they’re building not emblematic hits, but simply quality structures. In other words, what is happening is, as the President would say, a ‘routine work process’. But this is unlikely to be of much help in overcoming provinciality. The latter challenge remains for Russian architects to deal with. And that they are likely to succeed is not just due to the improving quality of Russian architecture, but also to certain historical patterns.

If we avail ourselves of the well-known pattern identified by Vladimir Paperny, in which Culture One values what happens abroad while Culture Two opposes it, then it turns out that the entire 20th century obeys this model faithfully: the 1920s loved the ‘abroad’; the 30s opposed it; the 50s and 60s once more loved it; the 70s and 80s once more opposed it. Then at the end of the century, as a result of ideological changes and informational transparency, the alternation of the two distinct cultures became less acute, but survived in a gentler form. In the 1990s Russia was open to the West; then in the first decade of the 21st century there has been a movement in the opposite direction. And so the arrival of foreign architects, which was justified and well prepared for by the 90s, has in the ‘noughties’ taken on the character of a strange opposition. The services of foreign architects are eagerly sought, but then, instead of the fruits of their labours being properly employed, they are abruptly discarded.

This situation is reminiscent of the watershed of the 1920s and 30s. In the 1920s Le Corbusier, Mendelsohn, May, and Kahn were all active in Russia. But the competition to design the Palace of Soviets was a dividing line. Nourishing illusions encouraged by the 1920s, foreigners (Corbusier, Mendelsohn, Hamilton) sent in designs, but as soon as they realized that there was no longer any demand for their work, that there had been a change of course, they stopped. Half of their designs remained unbuilt. The Tsentrosoyuz building had its legs bandaged; Corbusier renounced his authorship; and Anton Urban perished in the torture chamber. But Russian architecture began following its own path. And though the latter turned out to be infinitely far from the path of world architecture, nevertheless some utterly outstanding buildings were created. Buildings which Western stars today regard as fantastic (the view taken by Herzog and de Meuron of Moscow’s seven Stalinist high-rises).

For Russia the abroad is not at all what it is for any other country. It is much more than a matter of our neighbours on the map. It is a myth, a complex, a weak point in which love and hatred, desire and fear, attraction and repulsion, envy and pride, parroting imitation and self-humiliation meet on equal terms. Tsars are keen to invite foreigners, but they wash their hands after greeting ambassadors. This is why Russia has put up such a resistance to globalization – at least, in those fields where national pride has a historical basis.

You can’t escape the feeling that everything is stagnating in a swamp, even though there doesn’t seem to be any clear reason for this. A definitive picture of this depressing Russian darkness was painted by Andrey Platonov, who in the 18th century described in his ‘Epifani Sluices’ how the English engineer Bertrand Perry came to Russia at the peak of foreign success here to carry out a commission from Peter I to build a sluice between the rivers Oka and Don. Perry drew up plans, work began, and then everything fell into the usual pattern. The peasants who had been press-ganged to work on the project ran away; the subcontractors stole things; the German technical specialists fell ill; the military commander started drinking… Then it transpired that the research for the project had been conducted during a year when there had been an abundance of water in the rivers and now there was none, and, while expanding an underground well, Perry disturbed the layer of clay holding the water… The sluice was never built. Peter I had the Englishman executed. And ‘as for the fact that there would be very little water, all the womenfolk in Epifani knew that a year ago, so all the locals looked upon the work as the tsar’s play and a venture by foreigners.” None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

|