|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 17.04.2017 | |

|

Sigeru Ban: “The sense of achievement after completion of a disaster relief project and a common project is the same” |

|

|

Ekaterina Mikhailova |

|

|

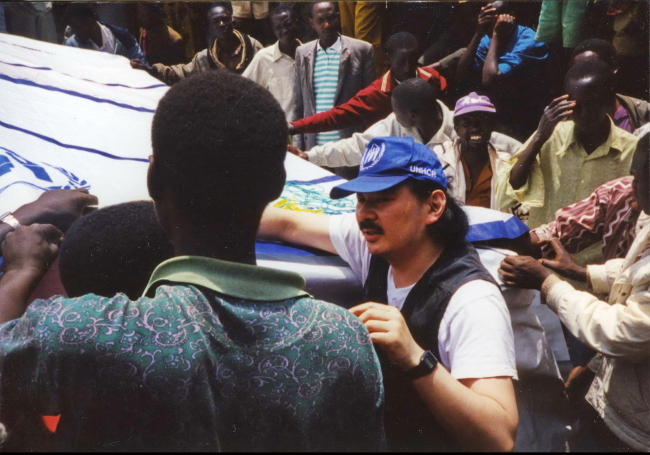

In this interview Shigeru Ban shares his vision on social responsibility of architects, specificity of disaster relief projects, idea of a paper log house and one of Ban’s most recent disaster relief initiatives – ñonstruction of temporary shelters and new housing, a Buddhist temple and an elementary school in Nepal. Shigeru Ban. Photo by Shigeru Ban Architects– You have been involved in disaster relief architecture over two decades. In which way working in disaster relief is different from ordinary architectural practice? – When I first started becoming involved in disaster relief projects, it was a challenge to balance the disaster relief projects and non-disaster relief projects. However, the only difference is whether or not the design fee can be obtained; the time it takes and sense of achievement after completion are the same. I feel that the barrier that had once divided the two categories is dissolved. Shigeru Ban with volunteers constructing Paper Emergency Shelter in Haiti. Photo by Alex MartinezShigeru Ban with volunteers constructing Paper Emergency Shelter for UNHCR in Rwanda. Photo by Shigeru Ban Architects.– When and why did you decide to be involved in disaster relief as an architect? – I always thought the recognition towards social responsibility of architects is weak in Japan. I decided to start disaster relief when the Kobe earthquake occurred in 1995. When the disaster relief activities had finished, I felt that I should organize the Voluntary Architects’ Network (hereinafter VAN) and continue to support it in the future. Today at VAN we work with several office staffs, university laboratory (Keio University Shigeru Ban Lab), and local architects and universities around the disaster-affected areas. Paper Log Houses in Kobe, Japan, 1995. Photo by Takanobu Sakuma.Paper Log House in Turkey, 2000. Photo by Shigeru Ban Architects– Was your decision to be be involved in disaster relief somehow influenced by the fact that Japan is located in one of the most active seismic and volcanic zones in the world? – Disasters can happen anywhere, and so do aids. The decision was not particularly influenced by that, but I was always concerned about the poor living environment for the victims in evacuation centers. Temporary housing built with paper tubes in Kobe in 1995 was the start of the disaster relief work, and we started to provide paper tube partition systems to protect privacy at evacuation centers since 2004 Niigata Earthquake. Paper House for Niigata earthquake victims. Photo by Voluntary Architects' NetworkPaper Partition System 4 in Iwate, Japan. Photo by Voluntary Architects' Network– How and when the model of a paper log shelter was invented? How has it evolved? – Paper Log House was developed when the 1995 Kobe earthquake occurred. Since the Vietnamese refugees who worked at the local shoe factory refused to relocate (in order to remain nearby the shoe factory), we built log house using paper tubes in a local park. After the first paper log house in Kobe, we have also built further developed iterations of shelters in Turkey, India, and the Philippines. Their designs were adjusted to each region after examining such factors as climate, culture, economy, religion and commonly used materials. Christchurch Cardboard Cathedral. Photo by Stephen GoodenoughPaper Concert Hall in L'Aquila, Italy, 2011. Photo by Didier Boy de la Tour– Is it desirable to make disaster relief architectural projects – universal in their nature? May there be one prototype of an emergency shelter/temporary housing/permanent housing after the earthquake struck applicable all over the globe? – Looking at previous relief activities, there are no specific houses or shelters that can be applied in every disaster areas. It is important to design houses and shelters appropriate to each environment after considering the culture, economy, and typical construction methods of the affected region. Paper Emergency Shelter for Haiti. 2010. Photo by Alex MartinezPaper Emergency Shelter for Haiti. 2010. Photo by Shigeru Ban Architects– There is a big number of natural disasters occurring throughout the world annually and it’s hardly possible to be involved in disaster relief of each of them. How do you choose places where you launch a disaster relief initiative? – It is true that we cannot go to all the affected areas, but we may decide to take action on our own after acquiring information about scale of damage and current conditions, or decide to go when we get requests. Wooden Prefabricated Temporary Housing – Kumamoto Earthquake, Japan. Photo by Hiroyuki HiraiWooden Prefabricated Temporary Housing – Kumamoto Earthquake, Japan. Photo by Hiroyuki Hirai– How and when have you learnt about the Gorkha earthquake? What was its coverage in Japanese mass media? – I was in Tokyo when the earthquake occurred in Nepal, and I learnt about the large scale of damage through the news. The earthquake was a big news in Japan, too. – Why have you decided to launch the Nepalese project? – A Nepali student studying in Tokyo sent us an email expressing that he would like to support those affected by the earthquake. Then I decided to visit Nepal and see the conditions in person. – The Nepalese project was planned to have three phases – emergency response, temporary housing and permanent housing construction. How did the project implementation go in practice? – Initially we visited the affected area to provide shelters that can be easily assembled with paper tubes. During the visit, we inspected the conditions and learned about their typical construction method, which is brick masonry, and high wood carving and processing techniques. Also, due to aftershocks, building that is resistant to earthquake was required. From this visit, the design for permanent housing arose. – What are the main differences of the Nepalese project compared to other disaster relief initiatives done by VAN? – Although it is not unique to Nepal, the design was generated after we carefully observed the economics and culture of the affected area, as well as construction customs and building materials, to best suit the local environment. – When constructing emergency shelters, you use three types of joints – with duct tape, plastic or plywood connectors. Which of them do you consider preferable? Which one was used in Nepal? – The Nepal shelter uses duct tape as joints, but rather than choosing which one is best, we are thinking about making optimal proposals from the materials readily available in the disaster areas. Nepal House Project. Photo by Voluntary Architects' Network– In Nepal you used a particular wall system that can be assembled by connecting modular wooden frames and infilling them with rubbled bricks. How have you tested this construction method? What were the results of those tests? – Bricks are infilled in the wooden frame to allow the timber frame to bear the structural load and to ease the house assembling process. We have conducted several structural tests in a university in Japan to test for seismic performance and compare results to Japanese earthquake resistance standards. The results showed that by fixing plywood onto the timber frame, there is significantly less deformation. One element that we improved after tests was the timber frame design, namely fixing plywood in order to enhance shear strength. Nepal Gompa Project. Photo by Voluntary Architects' Network– Besides providing people with housing, in Nepal you are keeping the tradition of creating a symbol of hope and recovery by constructing a temple (as in Kobe and Christchurch). How have you designed a Buddhist ecclesiastical fortification? – We are designing a Buddhist temple in a place called Simigaon. Basis is using the same timber frame system as that of Nepal project, and a circular atrium with paper tube columns is incorporated to create sacred spatial atmosphere. Secondary School in Khumjung, Nepal. Photo by Voluntary Architects' Network– One of your objects that are under construction now is Khumjung School in Sagarmatha National Park. How is it different from Hualin temporary elementary school in Sichuan province in China? – Hualin Temporary Elementary School is very different from the start. The Khumjung School was realized with the request from Doshisha University Alpine Club in Japan. Khumjung is situated at a much higher altitude, and we successfully utilized local construction method and materials. In Chengdu, on the other hand, we asked the local authority directly requesting to build elementary school while on our visit to affected areas believing we can provide support to those needed. Construction was carried out by Japanese and Chinese students and teachers, while in Khumjung, a local contractor was in charge of construction work. – What is your impression of Nepal as a venue for disaster relief project? (Were there any specific challenges for project realization posed by mountainous location, governmental administrative system or mentality of locals? Were there any particular advantages for project realization in Nepal?) – With many NGOs in Japan supporting, Nepal has a charm of attracting people. As regions around Kathmandu and those in the Himalayas have different available construction materials, the design has to be adjusted accordingly. For instance, the infills for the timber frames in Kathmandu region are bricks whereas stones are used in the mountainous regions of the Himalayas. – Do you trace the performance of your constructions (disaster relief temporary and permanent housing) when the project is over? Do you come back to disaster struck zones you were revitalizing after the project is over? – In Japan, we built temporary houses after the earthquakes in Tohoku (2011) and Kumamoto (2016). I still find time to visit these places and check what is needed locally. After the Kumamoto temporary houses were completed, we made a number of visits. After hearing back from the residents, we made furniture such as kitchen side tables to make best use of the space. – In your disaster relief projects you usually develop partnerships with local actors – universities and architects. How do you choose these local partners? What is their role in implementing the disaster relief project? – For the selection of project partners, we sometimes approach local universities or architectural offices, but we also at times receive offers from them. We often invite students to participate in the construction work, and ask local architectural offices to communicate with local authorities and contractors. – Implementation of disaster relief projects usually is done with the help of volunteers. What is the most challenging part of working with volunteers for you? – Working with volunteers stimulates design challenges, as it is important to think about the simplest construction methods and to provide safe construction environment in order to work with volunteers. – How do you usually raise funds for disaster relief projects? – We receive donations from individuals and companies. Several companies have been continuously supporting our projects. – Do you follow activities of any other architectural practice that launches disaster relief initiatives? Have you ever been cooperating with any of them? – Although not paying particular attention to the activities of other architects, we have been cooperating with AMDA, a medical NGO in Japan, for a number of projects. |

|