|

The text of interview for the catalogue of Russian pavilion of XI Venetian biennial

Andrey Vladimirovich, the first question I would like to put to you is: Do you think it’s right today to contrast the Russian architectural school with foreign architecture? Do you agree with the division into ours and not ours, into Russian architects and foreign invaders, on which the concept for the Russian pavilion at the Venice Biennale is based?

It’s a legitimate view to take, given there is a reality which sustains it. But, at the same time, if it’s possible to name – admittedly, not without omissions and reservations – the distinctive characteristics of the Russian architectural school, it would clearly be an exaggeration to speak of Western architecture as an integral system, and still less as a system opposed to modern Russian architecture. The division into ours and not ours is always a delicate matter. Our fellow Russians often see relations between Russia and the West as more tense than they actually are. Foreigners, at any rate, are rather less concerned about this subject. Personally, I think it more reasonable to posit a division into ‘outsiders’ and ‘natives’. Which is to say, I’m inclined to distinguish architects not in terms of nationality, but according to what approach they take to the profession. I regard as ‘outsiders’ those who consciously or unconsciously ignore the distinctive features of our cultural context – those whose activities are to one extent or another dangerous for our national culture. ‘Natives’ are, accordingly, those who have found their place in the context and merged with it. Traditionally shocking are the results of competitions involving foreign top-name architects and the solo performances of these celebrities in our country, in both of which blatant disregard for Russian culture is common. But at the same time we should not forget the great damage sometimes done to Russian cities and architecture utterly without intervention from abroad.

The current fears and phobias, a reaction to the increased activity of foreigners in our architectural market, have roots that are cultural, political, and historical. They go back to the end of the 1930s, when all links with the outside world were broken off and we were left to stew in our own juices.

What about Albert Kahn, who during those same 30s designed industrial buildings for half the USSR?

Kahn wasn’t alone; there was a whole horde of them. But they were all thrown out of the USSR in a single instant, in spite of the fanatical loyalty that many of them showed to the communist idea. One of the last episodes of collaboration with foreigners at that time was the heroic effort made by the Vesnin brothers to bring Le Corbusier to the Soviet Union… Essentially, they ceded to him the right to design Centrosyuz. However, the latter project ended in a scandal, with Le Corbusier renouncing his authorship of the building. After that, we went our own way.

But the coup de grace was delivered to Russian culture by Khrushchev with his ‘Resolution on Superfluity in Architecture’. It was then that architecture was altogether excluded from the category of art and completely subordinated to construction.

The above catastrophes had such an impact on the architectural profession in this country that we are still living with their consequences.

Which is to say, you base your evaluation of the influx of foreign specialists into Russia on historical premises and consider this a broadly positive tendency? We learn and they teach, is that right?

The main thing here is probably that our relations with foreigners are cyclical in character. Periods of love for and hatred of the West replace each other strikingly quickly and – and this is the funniest thing – independently of state policy. A blend of xenophobia and ‘veneration of the West’ is a paradox of our mentality which rules out working normally with foreigners or objective evaluation of what they do.

In addition to all the above, foreigners anyway come in different kinds. The foreigners who come here may be stars or simply professionals, but they may also be people who can teach us nothing. Visits from the first group are a blessing. Visits from the last – I would call them opportunists – are probably the norm, something that cannot be avoided. The main thing, in the final analysis, is that between us there should be that trust which is necessary between members of the same profession.

There are two ways of looking at this. You can regard the presence of foreigners here either as a potential source of conflict or as helping our integration in the global process. Probably, it’s both. How do you see your part in this process?

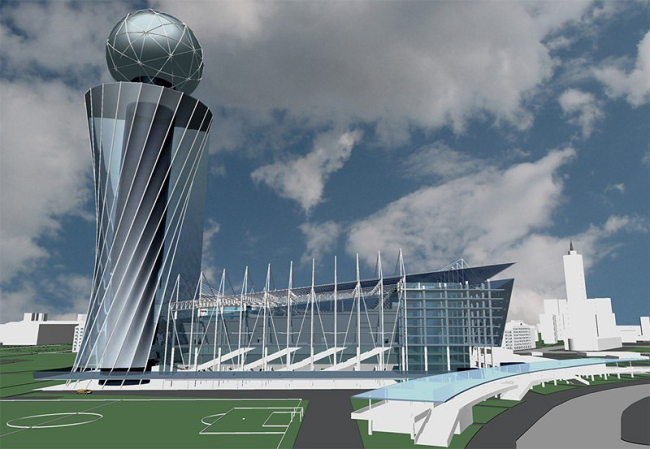

Unlike many people, I don’t see foreigners as aliens. I don’t have any complexes in this respect. They and I speak the same language. It’s another matter that I have a much deeper knowledge of life in Russia than they do: I would never propose what Perrault proposed for the Mariinsky Theatre or Kurokawa for the Kirov Stadium [in St Petersburg]. The latter two projects are utterly unviable. In all this I see the wrong attitude being taken to the brief… Which is strange, given that this is not typical for specialists of this class. Both the Mariinsky and the Kirov Stadium projects are full of irrational, contrived solutions whose inappropriateness will be all the more apparent at each successive stage of the design process. These solutions will not be realized.

The Mariinsky and the Kirov Stadium are possibly exceptions, the result of an insufficiently serious approach. In ordinary practice, people such as Perrault and Kurokawa don’t make mistakes; they do everything perfectly professionally.

In both cases I think the jury’s decision was based not on analysis of the projects, but on subjective feelings, on an a priori trust in artistic and charismatic foreign celebrities and on a profound scepticism – common among bosses and oligarchs today – with regard to Russian specialists, who tend to be looked upon as still inescapably Soviet or provincial. So I see my own role in setting straight our relations with our foreign colleagues as one of overcoming these views.

Am I right in thinking that in spite of the above particular instances, you are nevertheless generally in favour of integration with foreigners? Why? Is it a matter of solidarity? As far as I know, there was a time when you too were active in trying to get into foreign markets – in China and Germany. This makes you likewise a kind of invader.

Yes, I was once very interested in foreign competitions… However, this is not at all the reason why I have sympathy for foreign architects. About ten years ago, we did a lot of work for both the Chinese and the Germans. But our designs were never realized. Penetrating a foreign market is a time-consuming, troublesome business, and then no one particularly wants you to build in their country. It would have been necessary to concentrate fulltime on these projects, open offices there, invest large sums of money. Literally move there. That’s how all the Western firms operate when they work abroad. In our case this was no invasion but a series of one-off commando drops. We had neither the resources nor the time for a serious campaign and, even more importantly, there was work for us here. Europe is now in the grip of a recession. Construction work there has finished. There’s no work and everyone has rushed off to Asia and Russia. So I’m glad I live in Russia, where there’s theoretically enough work for everyone.

It’s currently fashionable to divide Russian architects into traditionalists and followers of the West. In tribute to this fashion, I would like to ask you which party you would put yourself in?

To be honest, I don’t find this division very comprehensible. It takes us back to the question of style, which seems to me considerably more fundamental than that of quality. Many people naively think that adherence to a certain style can guarantee success, when in fact success in our profession is guaranteed by something else altogether. I was amazed when I discovered archaic, historical motifs in works by vehement members of the Avant-garde such as Picasso, Mel’nikov, and Le Corbusier. These people worked outside all stylistic categories; they were each to himself – it was only later that critics began to associate them with this or that group. Or remember the surprising blend of Constructivism and Art Deco in the 1930s. Style does not play such an important role in architecture as people often think. For some people not belonging to a ‘party’ in terms of style is a sign of a lack of principles… But not for me.

The main thing is that a building should be worthy.

I’m more fond of the word ‘appropriate’, although ‘worthy’ is also a good word. These words are a good reflection of my attitude to architecture in general. You should understand that 90% of our commissions come from the Government of Moscow. We, Mosproekt-4, are a municipal organization that carries out commissions from the city. We, for example, cannot not react to the desire of the city’s management and the management of the Tretyakov Gallery to see the New Tretyakov building designed in the ‘Vasnetsov style’ – in, roughly speaking, the Russian version of early-20th-century Art Nouveau, a style that is slightly provincial, fragmentary, naïve. It’s not something I feel very close to. I have an idea of this style and how to work with it, but consider it best to use an artist who could be the Vasnetsov or, even better still, the Lentulov of our time. It would be great if this role could be carried out by a person as sensitive and delicate as Ivan Lubennikov, whom I’ve invited to take part and whom I see in the role of creator of this façade. This is a permissible approach, and one which I see as reasonable and ethically justified.

While we’re on the subject of style, your projects are stylistically very diverse, especially those from the last few years. Is there a theme that runs right through your work?

I suppose there must be. But what do you mean?

Well, for instance, the ‘sail house’ on Khodyynsk Field is stylistically very different, in my opinion, from the Ice Palace of Sport, which stands in the same district and is to be exhibited at the Venice Biennale this year. And your maternity hospital in Zelenograd is a detour towards Constructivism – a third style.

Architects are like writers. There are people who spend their whole life writing a single novel – usually about themselves. And there are those who write poetry, prose, and plays all at the same time while looking at the world around them and allowing themselves both to doubt and get excited and yet remaining themselves. Some have found and others are looking, looking for images and spaces. I am always slightly suspicious of the artificiality and sterility of a person’s life when he or she spends it following the same line, like a clockwork mechanism, and sings one and the same song. I can understand Le Corbusier, but not Richard Meier, who took one of Corbusier’s buildings and, like a good pupil, produced numerous interpretations and reproductions… The borders between styles were eroded altogether by the efforts of the Postmodernists in the 70s. The very concept of style, in my opinion, has lost its point. What remains is a publicly accessible set of media of artistic expression, which could and must be used. Although, personally, I’m a little disturbed by the heightened sensitivity to these media, to décor in particular, shown by both the general public and professional architects.

For me the essentially important thing is something else: space as such. Emptiness, which the architect must organize.

Furthermore, I have to repeat myself here, we are a municipal organization. You should understand that a state commission involves a huge number of planning approvals, continual dialogue with the authorities, and attendance of endless council sessions. And the only path to salvation lies through a spatial solution in which expressive media are secondary.

Spatial – in the sense of urban planning?

Partly, yes. Urban planning was how our generation entered the profession, in the same way that the next generation was shaped by ‘paper’ competitions. It’s widely accepted that the history of Modernism ended at the end of the 1960s, and that its final chord consisted of extremely productive, radical, and content-rich urban-planning concepts. Until the 1960s architects mostly dealt with single buildings. The urban-planning solutions proposed by Le Corbusier, say, were considerably more naïve than the houses he designed. It was only with the arrival of Team Ten and the Smithsons, who took a qualitatively different approach to the city, that we started to see multi-functional structures, a new feeling of urban space, and the idea of integrating architecture and urban planning. This was an utterly intuitive and yet quite deliberate movement, which mixed artistic media and languages with rational constructions and methods. Architecture was seen at the time as inseparable from urban planning and layouts. This is why I’m saddened by the decline in urban-planning culture and the complete indifference of society and state to the unique instruments which only architects possess for organizing Russia’s endless spaces.

On the subject of municipal commissions. Can I ask you a question from left field? How do you manage to combine your work as an architect with your functions as an administrator, academic, and researcher? You are head of Mosproekt-4, a member of the Russian Academy of Architecture and Construction Science, and the author of two books and more than 50 articles.

I don’t know how I do all this. There’s just no alternative. But it’s clear that I spend most of my time on activities that have no direct relation to architectural design. But were I not to pay proper attention to these activities, I would not be able to fight for our right to individual solutions. That goes for all architects. It’s another matter that many try their best to disguise these managerial gifts, preferring to seem 100% creative figures. They pretend to be artists, although they carry an arithmometre in their heads. It’s like Governor Brudasty from Saltykov-Shchedrin’s History of One Town, who has an organ fitted in his head. Success in this profession largely depends on having such an organ. But, of course, it’s also a matter of what you prioritize: what is primary for you – management or architecture?

Over the last 10 years you have worked with a huge number of people. The former ‘paper architects’ Dmitry Bush and Sergey Chuklov are part of your team. You worked with Boris Uborevich-Borovsky on the ‘sail house’ on Khodynka. How do you manage to find a common language with so many different people?

With each of these people, as with many others, I have shared years of working together and joint failures and successes. In general, I’m very proud of those who work in our institute. And for me the most precious thing is that they have themselves chosen to work here, in spite of the discomfort which often accompanies working on state commissions. These are people of a certain type, who are sincerely and thoroughly devoted to their profession.

Are you happy that of all your many designs it was the Ice Palace – the so-called Mega-arena – that has been chosen for the Biennale?

Well, that was the curator’s choice. I think he based his decision on the fact that this project is very different from all other modern buildings with similar functions. The current fashion is for enclosed and impenetrable heaps or drops. Like the Allianz Arena in Munich. You know, when you wander around it, you have no idea where north and south are, how to get in or how to get out. Mega-arena is an open structure. It’s completely different. And, I think, much more honest and appropriate.

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

|