|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 28.02.2017 | |

|

Archimatika: it’s time for “sleeping belts” to wake up. |

|

|

Darya Gorelova |

|

| Architect: | |

| Aleksandr Popov | |

| Studio: | |

| Archimatika | |

|

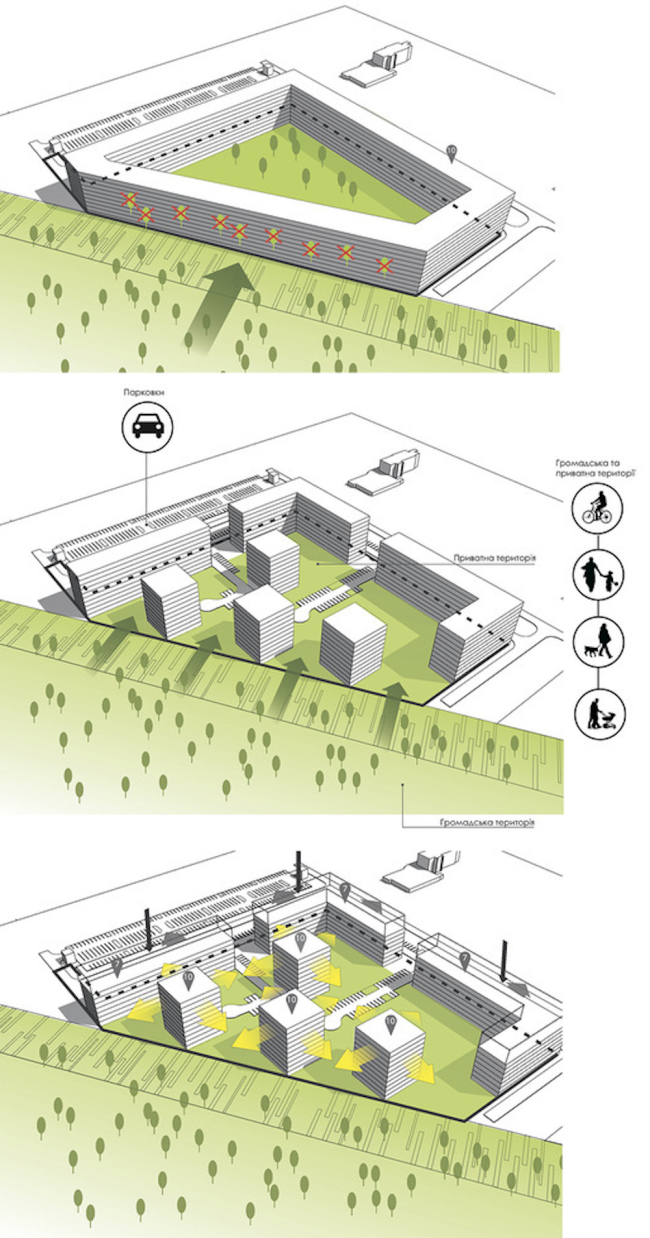

Uniting the imagery and the construction typology of a historical city with the lush vegetation of a “garden town”, Archimatika proposed for a peripheral yet actively developing area of Lviv a fragment of new-type city environment meant to inspire “feelings of a new quality”. The housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Park. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaThe historical center of Lviv is relatively small – about 120 hectares. One of the protuberances of the city territory, which touches the city transport ring, is stretched south and joins the Stryiska Street, a busy city thoroughfare. In its very beginning, near the park that bears the same name, this street can boast stucco eclectic façades and fine “Roman” pavements. Further on south, these give way to workers’ settlements, and then to residential areas and industrial parks. The territory of the new housing complex “Leopol Town” is situated between a factory and a hippodrome not far away from the city’s ring road. The three hectares occupy a corner of the derelict municipal tree nursery, which has now turned into a semblance of a forest. The surroundings are quite promising: the city’s bus depot is but a five minutes’ walk away, there is also the already-mentioned hippodrome nearby, and slightly further, a couple of kilometers southward, there is the football “Arena Lviv” which was built for FIFA 2012. There are also a few parks nearby, and there are small villages outside the city boundaries: from west and east. Currently, the urban area between the villages and east of the bus terminal is being actively developed – numerous new housing projects are being built, with the consideration of the proximity of the Arena and the city’s plans for renovating two of its highways: the Vernadskogo Street must turn into a span thoroughfare, while the nameless appendix stretching northward will be renamed into the Krasnaya Kalina Avenue. Leopol Town has at least four more neighbors with different degrees of construction completion, from 5 to 10 stories high. The complex that Archimatika designed is inscribed in the same height restrictions – it does not tower over either the soviet-time nine-story houses, or the new housing projects. The large – three hectares – land plot, combined with rather modest requirements for floor space – 43 300 square meters – allowed the architects to stay within a reasonable scale. At the same time, the complex is strikingly different from its neighbors, and not only from the standardized prefab ones, either. First of all, the architects paid a lot of attention to studying the architectural context, promptly reacting to all of its peculiarities. The rectangular territory of the former plant nursery, with a cutaway at its northeast corner, is essentially a triangle. From the right angle sides of the triangular land site, the future busy streets approach – therefore, this side of the complex includes capacious overland parking lots (there are no underground parking garages here). The buildings that stand where greenhouses used to be form a “contour” framework of an urban block type, as if protecting the land site from the city but their front is broken into three fragments, which provides free passages leading inside the complex, and helps to avoid the undesirable effect of a “Great Wall of China”. On the outside, alongside the hypothenuse, there are, of course, no parking lots whatsoever – instead, there is a pedestrian promenade running here that is meant to connect the bus depot and the bus stop on the Vernadskogo street with the future Krasnaya Kalina Avenue that will lead to the hippodrome and the Arena. A promenade is also one of the common decencies of the modern residential complexes, and, at the same time, the very fact that it will be placed not on the inside but on the outside, will make Leopol Town more open to the city and the forestland as well. The promenade is designed not only for the residents of the complex – the transient pedestrian stream could also make clientele for the cafés and shops on the ground floors. The housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Master plan. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaAs for the inside territory of the complex, the architects tried to keep as many of the old lime and ash trees as possible: they carefully searched for the places where to position the sports fields and playgrounds, and minimized the fire lanes and driveways down to the smallest allowable scale. The yard will only be opened to emergency vehicles and cars driven by people of limited mobility – ultimately, the yard has turned into a landscaped park of sorts. In addition, for the residents of the ground floors the architects designed small (about 3 square meters) little gardens on the inner contour of the complex. This hot trend of modern architecture – a piece of private space within a public landscaped territory, which makes it possible to lure people outside in their different capacities – becomes suddenly resonant, in this specific instance, with the rural surroundings of the new growing city. Within a fifteen minutes’ walk away from the bustling city people can, figuratively speaking, sit on their front porches, or have tea in the terraces, or even grow gardens of their very own. As for the ground floors of the outside contour, they will be occupied by cafés, shops, and other retail businesses. Speaking of preservation of trees and the “inland” forest that the complex got, the architects are mentioning the principle ‘invite nature in’ – and, indeed, if we are to look at the surroundings, the architects not just preserve the forest by fencing it off – they really let it in because the boundary between the complex and the outside part of the now-wild nursery was made as transparent as possible. The easiest thing in the world would have been to fence the territory off from all sides by a “wall” house getting a closed-type urban block – the authors share – yet they approached the task in a creative and flexible way, replacing the “wall” houses on the forest side with towers oriented strictly on the cardinal points, meaning, facing the hypothenuse boundary with their corners, opening up passages for going in and out of the complex. This way, people, and, conditionally speaking, trees, are “stepping inside” the yard: the boundary between the yard and the forest is transparent, and what we are looking at is one of the versions of the “garden” town, pretty much like a countryside health center or a university campus where the buildings stand amidst the forest. The difference lies in the fact that here the buildings stand closer to each other, while the trees are not just a pleasant site to see but they also perform a utilitarian function, helping to avoid the window-to-window view. The typology turned out to be of a mixed type: three sectional 7-story houses on the outside contours and four 10-story towers inside. The housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Layouts. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaThe housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Park. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaThe housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Yard. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaIt must be noted that the architects not only paid attention to the transparency or even porosity of the residential area that they designed – which makes it possible to cross it from side to side in any direction – but they also provided theoretical rationale for this solution, turning to the prototypes lying in the historical center of the city. The architects analyzed the historical part of Lviv on two parameters: “construction density / street space” ratio and the number of end-to-and passages from one street to another, which make it possible to traverse the entire city from end to end through arches, alleys, and side streets. Then the architects applied the resulting figures to designing their own brand-new complex. Therefore, the project not only reacts to the current and future needs of the territory – the architects also endow the new complex with immanent qualities of the old town, similar to the urban genetic code, “replanting” them from the center to the suburbs. Calculated and borrowed from the famous UNESCO-protected Lviv’s historical center, the specifics of volumetric construction make the new complex, which is built on the other side of the soviet “micro-districts”, flesh and blood of the old town in some secret way. The “genetic code” is a very apt term in this case because, speaking about the use of the urban meta-base, the architects turn their new complex into some sort of a relative of the city’s historical center. The housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Birds-eye view. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaBut then again, the parallels are drawn not only between the lines. The parceling of the construction is also resonant with the old town: less than 20 meters from door to door of the hallway entrance, and diversity of the façades of the block-and-section part. The façades of the sections, which will be built at the same time, are meant to imitate the naturally dense construction of the city center – also a modern technique that makes it possible to fracture the façade front thus making its look “human-friendly”. “What we ultimately wanted to get was this sort of a finely ground system that would partially resemble the historical buildings of the city center, that would be co-proportionate to human beings, and at the same time contemporary” – shares the chief architect of the project Dmitry Vasiliev. However, the architects think beyond just the “hot-trend-of-today” technique, building up a whole chain of hints at the imagery of the historical Lviv. For example, the seemingly freehand variations of the height of the sections – half a story high – resemble the silhouette of the buildings that frame the Market Square (the main tourist attraction), where the pitches of the roofs are also longitudinally oriented, while the ledges formed by the small variations in the height of the buildings are close in their proportions to what we see in “Leopol Town”. It’s not that such ledges are not to be found in their places and other cities – but in this specific instance the similarity with Lviv is enhanced by the details: the pattern of the mansard windows resembles the dormer windows of the Market Square. The cold green hue of the copper oxide and the dark-beige plaster of the façades with striped wooden shutters also put one in the mind of the city center. The light-colored façades add a “coloristic” note, which in this case completes the theme, reminding us that in the old town the dark-stone façades alternate with light-colored stuccoed ones. One of the final strokes is the chimneys, or, rather, the elongated outlets of the vent shafts that certainly look like ones. Together with the fine pavement, they complete the play of the parallels being drawn with the historical Lviv, carefully teetering on the verge of the recognizability of the prototype without falling down to stylization. The housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Yard. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaThe housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Birds-eye view. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaAs far as reality and the modern age are concerned, these are brought back to us by a variety of modern techniques: the doubled rhythm of the floors, very much like the Holland wall, the picturesque composition of the windows, the “wrapping around” of the towers with a casing of pitched-roof silhouette, as well as the inserts of grass-green panels and the horizontal stripes of dark stone that almost looks like wood – all of these establish imagery connections not with the Old Town, but with the immediate vegetation context. And, of course, the sign of modern age – the verticals of the flat-roof staircase and elevator units that stand outside the building, as well as the planes of the terraces in front of the penthouses – unlike the historical construction, where the pitches of the roofs would cover the attics, which, as is known, keep the warmth, in this case the triangles of the top floors are occupied by two-story apartments. The housing complex on the Stryiska Street in Lviv. Terraces. Project, 2016 © ArchimatikaNone“The pool of our early versions of the project included both flat and pitched roofs. But when our clients showed the project to the focus group, almost 99% of the respondents voted in favor of the gabled silhouettes as more inviting and “looking like a home”. “This was not the first time that we built houses with gabled roofs. But it was the first time that I saw just how differently people reacted to modern shapes and gabled roofs” – Dmitry Vasilyev recaps. Another Archimatika project, all but completed, also boasting pitched roofs, is the merrily-colored “Comfort Town” in Kiev. The similarity between the housing complex in Kiev and “Leopol Town” are rather apparent. However, while the architecture of the Kiev complex is designed to bring out emotional associations of “Europe in general”, the Lviv complex selectively draws from this theme individual “conceptual hooks”, tying its romantic image to the genius loci, at the same time keeping a fair share of “Christmas” quality – all of the pictures are of the winter kind, too. The architects view this project as an attempt to offer this city not just another new housing complex but also some certain strategy for developing a full-fledged living environment. It’s time for sleeping belts to wake up – in the XXI century the quality of their architecture is quite capable of holding its own with the architecture of the historical center of the city. |

|