|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 09.08.2016 | |

|

INION: the perfect library and a citadel for the lyrical and humanities-minded type |

|

|

, Nikolai Malinin |

|

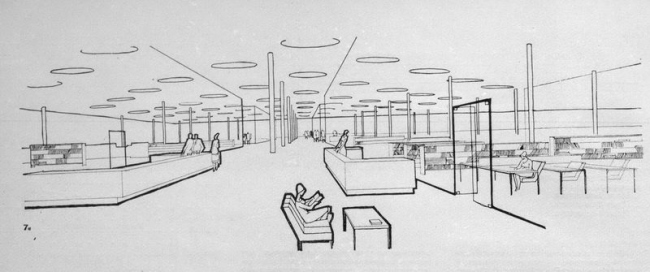

|

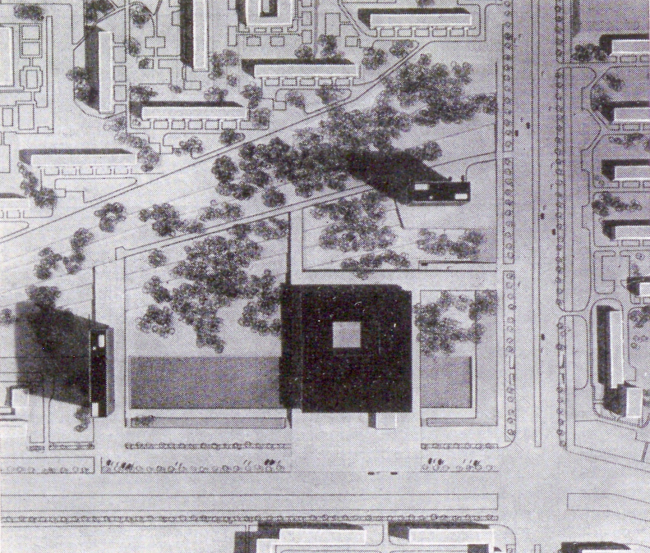

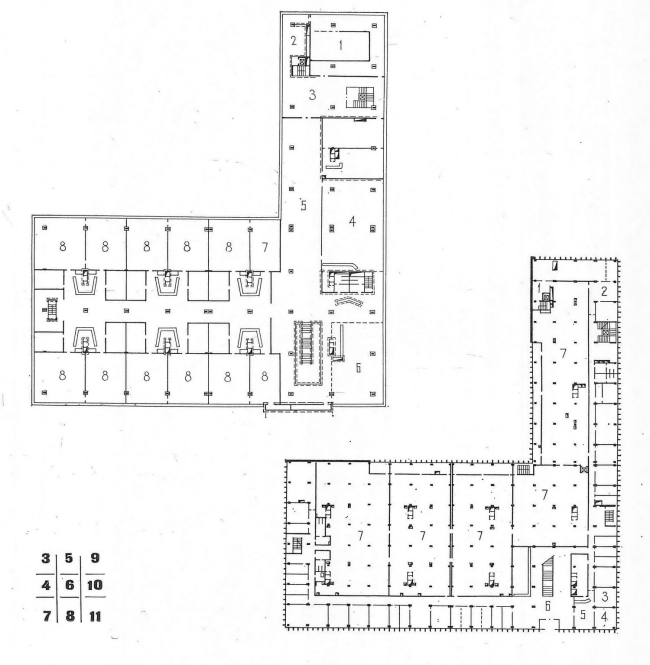

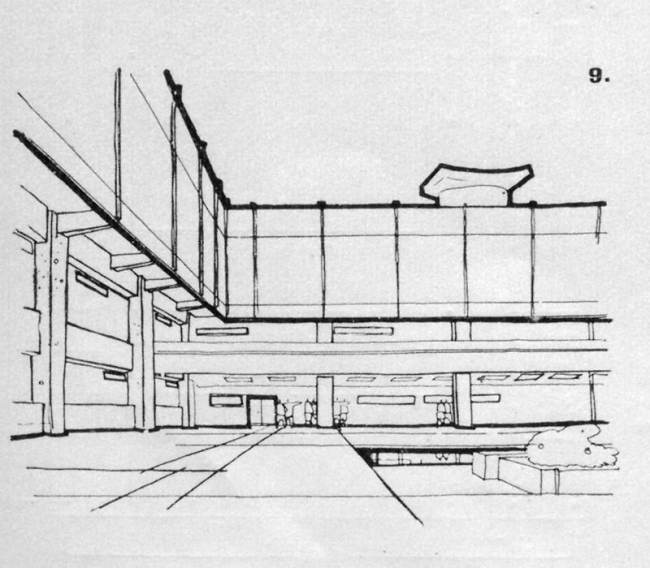

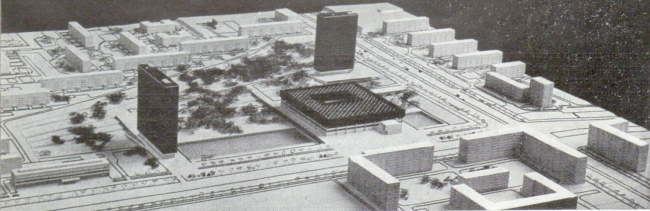

In connection with the current contest for the best project of restoring the INION building, we are publishing a chapter about it taken from an Anna Bronovitskaya and Nikolai Malinin book "Moscow: Architecture of the Soviet Modernism. 1955–1991" that is due to be published by "Garage" Museum in October 2016. Right about this time, a contest is underway for the best concept proposal for reconstructing the INION building of the Russian Academy of Science. The contest has been organized by the winner of the tender for the survey and design work on restoring that building – OOO "Project Organization GIPROKON". The seven finalist contest projects were showcased until the 15th of August in the Museum of Architecture (Vozdvizhenka St, 5/25), in the Russian Academy of Science (Leninsky Avenue, 32a), in the building of Moscow State University of Civil Engineering, and in the building of Federal Agency for Scientific Organizations (Solyanka St, 14). The winner was to be announced on the 16th of August.  Project of the group of institutes near the Profsoyuznaya Metro Station. Photo of a model // "Building and Architecture of Moscow, 1965, N8, p. 18Project of the group of institutes near the Profsoyuznaya Metro Station. Photo of a model // "Building and Architecture of Moscow, 1965, N8, p. 18Jacob Belopolsky started with the master plan of the land site: placing the low-rise elongated library building closer to the crossroads, he flanked it with two multistory slabs of science and technology institutes well visible from a distance. The architectural jargon of those days called this technique of creating an architectural ensemble "complementing a bar with stumps". These three volumes, in full accordance with the Corbusier principles, were to be surrounded by a park. The park was separated from the traffic way of the Krasikova Street (Nakhimovsky Avenue) by a long rectangular reservoir. This reservoir performed three functions at once. First of all, it alleviated the height difference between the street and the lowered construction site. Second, its water was used in the building's air conditioning system. And, third, it was a very cool compositional element: the water surface reflected the architecture, and when the fountains were on, it looked like the top of the building was hovering above the ground. Plans of the 2nd and 3rd floors // "Building and Architecture of Moscow, 1974, N8, p. 14 Project of the interior design of the newsroom // "Building and Architecture of Moscow, 1965, N8, p. 20Project of the courtyard // "Building and Architecture of Moscow, 1965, N8, p. 20According to the original design, the library's building had a quadratic plan, had a courtyard, and was resting on a broad platform that was thrown across the reservoir and the park's lowland. In reality, however, the platform shrank to the size of a small bridge leading to the main entrance, the reservoir got shorter, now falling short of reaching the foot of the neighboring Central Economic and Mathematical Institute, and, furthermore, only two sides of the quadrant were ultimately built - the corner they formed embraced the would-be courtyard. It was planned that the square would be completed in the second stage of the construction but that never came to pass. Overview. Photo taken in the 1970's © IMOOverview. Photo taken in the 1970's © IMOOverview. Photo taken in the 1970's © IMONevertheless, the authors were able to implement the main points of their concept. The archives and the storerooms are situated in the two bottom floors, while the third, the top one, is entirely occupied by newsrooms and study halls. Having visited a few newly built libraries abroad before getting down to designing his project, the architect hoped that this layout would provide the readers with an easy access to the bookshelves: from the newsroom, subdivided into subject zones, one could easily find his way around to the department he needed, descending the staircase. Alas, the soviet library regulations forbade letting unauthorized persons into the archives. On the other hand, a quick book delivery system was organized - the books were delivered to the librarians' counters by conveyor belts. The delivery process was further sped up by the electromagnetic mail. The manually filled out forms were rolled into tubes, confined into cylindrical containers, and placed into a slot of the corresponding department. The power went on, and, drawn by the electromagnetic field, the container instantly travelled to the required department where all that the employee had left to do was take the books off the shelf and put them on the conveyor belt. Some wizardry! Interior. Photo taken in the 1970's © IMOThe nation's main organization that gathered, systematized, and referenced the literature on social sciences was to be a library par excellence housed in a building of a world-class architecture. By the standards of 1960, this allowed for rather broad borrowings from different architectural styles. And, while the master plan and the overall appearance of the building obviously point to the fact that Jacob Belopolsky was influenced by the postwar works of Corbusier (the project of United Nations Headquarters in New York City, 1947, plan of the reconstruction of Saint Dieu, 1945, La Tourette Monastery, 1953–1960), in the interior design he was obviously inspired by the example of Alvar Aalto. Just as was the case with the Vyborg library (1935), the newsrooms are lit by upper lights through circular light bulbs, the only difference being that in the Aalto project there were 57 of them, and Belopolsky had a cool number of 264 – feel the magnitude of the nation's main library! The architects were able to make both the outside walls and the partitions of the third floor completely glass, thus visually creating a single space. All the furniture in the newsrooms and study halls was low so that nothing would obscure the magnificent sight of ceiling covered in arrays of circular lucarnes. Life, however, immediately made its corrections: the librarians insisted on placing bookshelves with the new publications along the glass walls trying to form a more habitual enclosed working environment. The authorities' hopes were not justified either. Created on the basis of the library, the Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences became not so much the center of achieving the communist dream as the breeding ground for liberal freethinking. But then again, the fresh foreign literature and the coveted "Proceedings of the University of Tartu" were only accessible to the selected few: INION would only serve the members of the Academy. But this circumstance only added to the attractiveness of the library's image as the nursery of the highbrow humanitarian knowledge. The deplorable state in which the soviet Academy found itself, never being able to adapt itself to the realities of the post-soviet world, lead INION to a tragic end. The worn-out wiring, the malfunctioning fire alarms and firefighting systems lead to a fire that in February of 2015 destroyed most of the unique book stock and did a considerable damage to the building. The city has made a decision to restore it but who exactly will do it, when, and for whose money, is still unclear. The INION building of the Russian Academy of Sciences © Yuri PalminThe INION building of the Russian Academy of Sciences © Yuri Palmin |

|