|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 16.03.2016 | |

|

"Without resistance nothing is possible" |

|

|

Ekaterina Mikhailova |

|

| Studio: | |

| heneghan peng architects | |

|

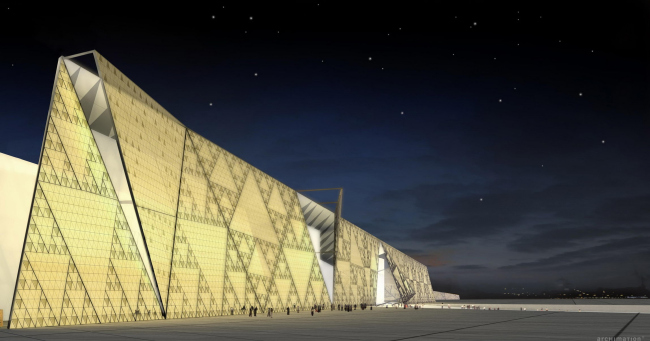

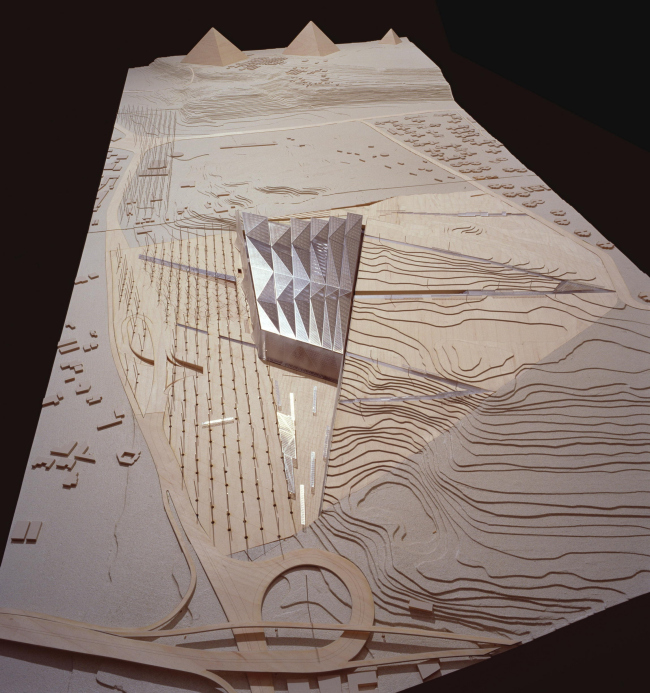

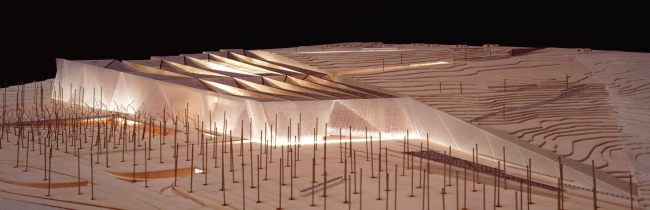

Interview with heneghan peng architects, a Dublin-based architectural practice, on designing museum buildings, Irish contemporary architecture and specificity of working in Russia. Archi.ru: Giant’s Causeway Visitors’ Centre © Marie-Louise Halpenny– You mentioned “working against” and “working with”. Which of these approaches do you use when designing within UNESCO World Heritage Sights? How did you find the compromise between past and modernity? Róisín Heneghan: – We have worked both in ancient settings as the Pyramids and Greenwich and in some naturalistic sights like Giant's Causeway and the Rhine valley. Every time we try to find something to work with there. The UNESCO World Heritage sights are considered beautiful and special places. So in a way you just have to pay attention to them. We should be doing it in every place: we should always pay attention to where we are building. There is no reason that modern buildings can't go to historic sights. Look at Greenwich where we've just finished a building. There was a Queen’s House by Inigo Jones and some buildings by Christopher Wren dating back to the 17th century but at the time they were all modern buildings. Giant’s Causeway Visitors’ Centre © Marie-Louise Halpenny– What degree of iconicity do you want to have in your museum buildings? Shih-Fu Peng: – We are completely the opposite of the icon. We don't believe in the icon. As I've always said, the world of icons has no icon. There's a point where it just becomes iconic overload and you cannot tell this one from that one. I think there are enough talented architects in this world doing iconic buildings. They don't need us anymore and we are not very good at making icons either. We do not believe that the building and its iconic value created by a talented individual should ever become the focus of the museum. The best example would be the Egyptian museum. You have the three pyramids and our site, the cone which is exactly aligned with the pyramids. The museum is about the pyramids. If you remove the pyramids, the triangle building looks stupid. It makes no sense. So it's about the icon of the distance of the two kilometers between the building and the pyramids. We are like archaeologists, we expose what is already there, we make people see things. It's like Michel Foucault: he doesn't invent anything new, he just exposes the conditions within society that are present at that time. The other thing we did with the Egyptian museum is that we built it at the edge of the desert plateau. The client was clever enough to pick the site exactly at the point of this symbolic and geological condition. The museum is nothing more than the cliff face. The translucent stone wall that we made is nothing more than an expression of this symbolic geological condition in the landscape that separates mountains and the desert or life and death. The Grand Egyptian Museum © heneghan peng architects The Grand Egyptian Museum © heneghan peng architects– Speaking about the Grand Egyptian Museum, why does it take so long to complete this project? At what stage is it now? Róisín Heneghan: – We won the competition in 2003. We were contracted through the design phase in a series of contracts and finished the Giza construction drawings in 2008. After that there was a lot of discussion with the Ministry and the project actually started on site in 2012. I think the current completion date is 2018. If you go to the Google Earth web-page, there is a fairly recent photo of the project there, with a concrete roof in parts of it. – Is the slow down of construction related to the Arab spring and namely to political changes in Egyptian government? Róisín Heneghan: – In a way, our involvement was almost stopped in 2008. Hence, I'm not exactly sure what impact the whole political change in Egypt had on carrying out the project. There definitely were some consequences as the previous ministerial team was replaced with a new set of people and some of them didn't understand our design idea. The Grand Egyptian Museum © heneghan peng architects– How do you supervise the Giza museum building process (if you do at all)? Róisín Heneghan: – We don’t. We answer questions on some design changes. Honestly we don't have the role we would have liked to have. There have been some negative design changes that can’t be undone. – Róisín, in your TED talk you described elaborate tests of materials that you used for the Grand Egyptian museum and Giant’s Causeway Visitors’ Center. How have you chosen fabric for the Palestinian museum and the National Center of Contemporary Arts (further referred to as NCCA) in Moscow? Róisín Heneghan: – In that talk I referred to the Giants’ Causeway Visitors’ Center and the Cairo museum as in these two cases the stone was used in a rather complex unusual way, in a way for which it hasn’t been tested. Thus, we have to carry out our own tests. In the Palestinian museum we used limestone, a traditional material, in a commonly used way. As for our Moscow project, its complexity is in its structure, not in the material. – The Palestinian Museum is said to become the first energy efficient green building in Palestine. Has this pioneer eco-friendliness complicated the process of project realization? Róisín Heneghan: – It was challenging sometimes to keep up to the energy efficient standard, as it's different than just building. For instance, paying attention to installation of thermally broken windows is not necessary to finish the construction but it is essential for achieving energy efficiency. Mittelrheinbruecke in the Upper Middle Rhine Valley © heneghan peng architects– You had won several commissions on bridges including the Central Park Bridges in the London Olympic Park and the Mittelrheinbruecke. How do you usually approach bridge projects? Shih-Fu Peng: – Bridges used to always be done by engineers. The engineering has been more of a driver of the bridge than its design. Often the bridge goes across hundreds of meters with just two columns. You cannot move the column a little bit, the bridge will fall down. It doesn't work. When we are involved in a bridge project, we start with an engineer very early. Recently the urban environments, the cities in which we live have become quite important and bridges do happen in cities. Bridges in cities cannot just be about engineering, they also need to be about design. The weirdest thing about bridges for us is that we are not interested in the bridge at all, as generally the bridges that happen in cities are quite short. What makes them the most difficult is actually how they land. Not the bridge. Once you get on to the bridge it is easy. Everybody can do it. So we start with the landing. How does the bridge meet the landscape, what are the conditions and the landscape that the bridge needs to address? What kind of traffic and people are there, where are people coming from, is there enough land to come down? Our view is not always right. We lose much more than we win but that's typically how we approach it. London Olympic park bridges © Hufton + CrowLondon Olympic park bridges © Hufton + Crow– How do you usually choose competitions to take part in? Róisín Heneghan: – We look at the jury. Then we ask ourselves whether it is an interesting project of a sufficient scale. Then we definitely look at the amount of work to enter the competition. If you are doing a big open competition, you don’t want to go into excessive details immediately. For the Egyptian museum initially we were asked for five A3s. It was a very manageable amount of work. Then we were down to twenty and then there was a lot more work. For the Giant's Causeway which was a completely open competition we were asked to submit three A1s. For Moscow there was a pre-qualification and then we were down to twenty. – How do you work with an unfamiliar context? Róisín Heneghan: – We definitely look at the site, try to get the understanding of climate and some sense of the place. Having said that, we’ve made lots of mistakes and got things widely wrong in some places. For instance, in the Middle East we didn’t quite appreciate that public space needs to be very protected and outdoor activities are very limited because it’s very hot. We tried to bring the European sense of the outdoor space where it is seen as something central and wonderful. It is a bit easier to work in Europe. Of course, there are differences here as well but there is also a common language and a common understanding of the relationship with the outdoor space. National Center of Contemporary Arts in Moscow © heneghan peng architectsShih-Fu Peng: – Indeed, we come from a particular age of education where we have to understand the site. Our analysis and what we did for NCCA is based on the site. If the exact site conditions would have existed somewhere else, we would have done something similar. In some ways we had to win the Moscow competition because it was done at the strategic level. The site is on the Khodynskoe Field, the entire new park looks on the biggest shopping mall in the world. Everybody said that that's the urban problem, hence everybody did a horizontal building to block it. National Center of Contemporary Arts in Moscow © heneghan peng architectsWe thought that there's not enough program to block it, otherwise the building will be too big. So we said: forget about blocking it. We did a vertical building to change the focus from looking at a shopping center to looking at the tower. So conceptually it would be the same as the Eiffel Tower. If you go to Paris and look at the Eiffel Tower, the city behind is still there but because you have a tower that's vertical and sat against the horizon, you look at the tower. So we solved the problem without solving the problem, we cheated. National Center of Contemporary Arts in Moscow © heneghan peng architectsThe form of the building is actually quite Russian. We are always asked why do we have so many cantilevers. My answer is that we are in Russia, the modern cantilever is invented here, how can we not do a building with it. The whole new museum is literally about the cantilevers. I always say the more you compress the cantilevers, the more it becomes an American skyscraper. American skyscrapers in some ways are perfect economical objects. The cantilever is the exact opposite of this expression. We find it modernist Russian. – Russia is not an easy place for work for foreign architects. What are the main positive and negative sides of executing the Moscow commission up to now? Róisín Heneghan: – The way that we like to work is that we do all the early design work and then somebody else takes the job while we remain involved as reviewers. It wasn't possible on the Moscow project. We are design advisers in this project. It means we’ll be involved during the entire construction process which we like. On the one hand, we were a bit surprised that we couldn't be more involved. On the other hand, our partners in MosKomArkhitektura were very willing to listen to what we had to say. Russia has very rigid codes, compared to working in London, it seems that in Russia you can’t really negotiate as much. Shih-Fu Peng: – Besides we were surprised with the abundance of rules in Russia and the ingenuity through which you can manipulate them. In any country rules cannot capture one hundred percent of the people. There's always a ten percent that falls out, this is the back door. At the end of the day you can’t stop people from inventing. They will always find a hole. So that ten percent find ways to reread the rules to get through them. That is what I find most interesting: Russians know how to play with the rules so well. – What is special about your work in Ireland? Róisín Heneghan: – Here, in Ireland, and perhaps in London too we are much more familiar and much more involved in the construction. Now we're doing a renovation of the National Gallery of Ireland and we are on site all the time. The advantage is that you really get to know the building, you know the context and how people move around this space very well. The downside is that sometimes it's hard to step back. You take all of the assumptions that everybody has and you don’t question them. The privilege of an outsider is to say that it doesn’t have to follow the habitual way. Extension of the National Gallery of Ireland © heneghan peng architectsExtension of the National Gallery of Ireland © heneghan peng architects– Do you feel connected with Irish contemporary architecture? Róisín Heneghan: – Honestly we never felt very representative of Irish architecture. Even though I'm Irish and I went to college here, later I went to the U.S. and Shih-Fu is American. We both studied in the U.S. Although at the moment we are based in Dublin and obviously when we work we bring in a certain amount of that, we didn't come through this system as much as some of other Irish practices (like Grafton Architects or O’Donnell & Tuomey). – You had started in New York, then relocated to Dublin and later opened another office in Berlin. What were the reasons behind these moves and what were their results so far? Róisín Heneghan: – We did start in New York because that’s where we were working at the time. Then we won a competition in Dublin. It was too hard to do it from New York and there was no reason to stay in New York in a way. In Europe there is a much stronger competition culture for younger practices, so we thought we can relocate to Dublin. Our first commission in Dublin was fairly big, it was an office building with 40 million € construction cost that gave us a base. As for opening our Berlin office, we had some people working in the office from Germany. One of our German employees wanted to move to Berlin. We wanted him to stay with us and we had a project in Weimer at that time, thus we decided to open another office in Berlin. Now there are five employees in our Berlin office. – Shih-Fu, how do you find living in Ireland? How was it for you to relocate here? Shih-Fu Peng: Generally, I think the place doesn't matter for us. We haven't really had the luxury of choosing where we live. From the business point of view, it's actually quite good here. There is an abbreviation FLAP, it stands for main European airport hubs for business - Frankfurt, London, Amsterdam and Paris. Ireland has developed in Dublin a highly competitive airport hub for tourists using which is two-three times cheaper than using FLAP. So there are some advantages of being located here too. – It seems you have quite an international team. Róisín Heneghan: – We probably still are half Irish, then we have quite a few Germans and Poles. We used to have more international people but then when the recession came to Ireland many of them left. – You started as a small team and then you expanded. What were the main challenges of such an organizational change? Shih-Fu Peng: – When we won the commission on the Grand Egyptian museum, there were only three people in the office. By the end of this project our team was over one hundred (with about forty employees in our office). Obviously we have ups and downs. The task number one for us is to let go control. If you look at the world top leaders such as the prime minister of China, they are engineers, not architects. Architects can’t run countries; they want too much control. We worked with architects that did big buildings, from them we actually understood the logic of it. At some point we decided partially to become project managers, not architects. We subdivided the entire project in such a way that different people can do different components. Those components usually are quite obvious. For example, in Moscow you have a park in the front and the tower in the back, the two are inseparable. The tower has much less impact if it was within the city landscape. Its power is like a pagoda in the Japanese garden, it becomes the focus of the entire park. In New York it would make very little sense. – It’s stunning that you started such a big international commission as the Grand Egyptian museum with just three people in your team. How did you manage it? Shih-Fu Peng: – What we did, we said that the entire project is one project whether inside or outside with the building grid across the entire site, inside and outside. So the bench in the landscape is on the building grid. Within the building grid we have subgrids which describe what's inside and what's outside, what’s above, what's below, the geometry of the Nile park with exactly the entire site which crisscrosses between death and life in some way. That's effectively how we did a project which needs a hundred people with three people - we just managed the grid. – Róisín, you lecture in several universities. How does this interaction with students influence your work? Róisín Heneghan: – It is invigorating to have a conversation with people who are thinking about something really intensely, who have some great ideas and work hard to try to get them going. Work at the office is very practical, there is a burden of contracts or budgets. Lecturing gives me an opportunity to investigate more conceptually, to talk about ideas and think more freely. – Given your teaching experience, how did you want to arrange the learning process for young architects with the Greenwich School of Architecture project? Róisín Heneghan: – We wanted to focus the School around the studio that would provide students with a big comfortable space where they could make models, draw, do the work and see other students. You know sometimes everybody gets stuck. When it happens, it is good just to walk around and talk to others, see what others are up to. Architecture school of the University of Greenwich © Hufton + CrowArchitecture school of the University of Greenwich © Hufton + Crow– When you work, what usually inspires you? Shih-Fu Peng: – It could be anything. I actually don't start competitions. I actually don't have any idea at the beginning. I have to generate a field, one that is called the primordial cloud of dust. I need to have something to work with. I'm a very good critic. I swim in the morning. In fact, swimming is the only possibility for one to be by himself in suspension, that allows one to think and do a lot of ideas. I guess this is the reason why Le Corbusier swam too. – Any advice to young architects? Shih-Fu Peng: – We can give ideas about how to do competition but not about how to become an architect. I hate saying that everybody has their own way of doing things but the strange thing is that people tend to approach things very differently. Somehow they may all get to the same point. You have to work. Very few people are born like Frank Gehry, and even he probably works very hard. – How does your dream project look like? Róisín Heneghan: – I’d like to build an airport. I hate that airports turned into places of security. It would be interesting to make a small airport that could still have the magic of flying. Shih-Fu Peng: – Personally I don't care. The more difficult the project is, the more problem solving it requires, the more interesting it is. If the client gave us half a billion dollars and said here is a site, build me a building and don't worry about the cost - I don’t want to do it. If the client says: I only have half a million dollars, the site is a highly contested territory, there is no water supply there, etc. - then we're interested. There is a good saying of Rem Koolhaas. Once he was asked why he wouldn’t build a house for himself. He replied: then I have nobody to argue. Without resistance nothing is possible. |

|