|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 19.02.2016 | |

|

Sergey Tsytsin: "We must try and learn to hear the music of our spaces" |

|

|

Irina Bembel |

|

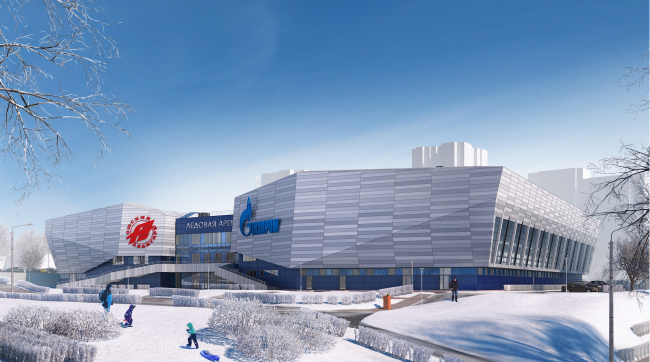

| Studio: | |

| Sergey Tsytsin’s studio | |

|

A conversation with a Saint Petersburg architect Sergey Tsytsin: about town-planning rules and regulations, working with a historical context, and about the difference between bureaucratic hurdles and system support. Sergey TsytsinArchi.ru - How did you come into architecture? Sergey Tsytsin: - Well, that was simple, really: my father, Victor Nikolaevich Tsytsin, was an architect - he first graduated from an art school, and then he graduated from the Academy of Arts. Me and my brother (the artist, Nikita Victorovich Tsytsin), were in the habit of drawing ever since our childhood, so the choice of our professor came naturally. After school, I enrolled at the Academy of Arts where I studied at the studio of Igor Fomin. He was an aristocrat when it came to architecture, and learning from him and his great personality was important to me. My other teacher was Alexander Vladimirovich Zhuk, with whom I established a true connection. In addition, the very walls of the Academy, together with its unique spirit did as much to educate us as our teachers themselves. What was also very important was the free communication between the students of different courses, we learned from each other. - Speaking of those days, were you already developing any of your priorities, or professional values in architecture? - Maybe I am not your average type but during my college days I simply imbibed everything that I heard from my teachers. At the same time, I would often ask questions, and sometimes I would catch my teachers off-guard - they would confess that they had never given a thought to the things that I was interested in. - How did your career develop after you graduated? - I started asking around and ultimately I made an informed choice in favor of Lengrazhdanproject. First of all, I've always liked everything that was related to town planning, territory development, functional zones, and the natural/artificial environment ration. In addition, by that time I already developed a certain attitude related to de-urbanization. I was lucky: by the time I entered the Academy, they ran a contest for the best architectural proposal for the settlement of Imochenitsy that is situated next to Vasily Polenov estate. I won this contest and later on this project was named the best in the USSR - it won the contest "project of the year", first on the city, and then on the republican, and then on the national level. I was did what one might call integrated architectural design: I developed the volumes and the plan of the settlement with an administrative and shopping centers, a kindergarten, a school, and engineering facilities. Parallel to that, I studied the architectural tradition of the Russian north, the compositions of those remote villages... Unfortunately, back in those days, the Agriculture and Industry Complex was only interested in standardized mass construction, and, in spite of the ministers' orders, this experimental settlement was never actually built. Only parts of it were implemented still later, during the perestroika, on the wave of reforms. I worked on Lengrazhdanproject for six years and completed a lot of planning and voluminous solutions. Later on, I worked at the studio of Veniamin Fabritsky where for three years one of my coworkers was Sergey Tchoban. Now, when we meet, we always remember those days with warmth. Still later on, the perestroika started, and I was invited to the Saint Petersburg Architecture and Construction Institute, where I taught at the Student Construction Bureau. Among the people who also worked there was Mark Khidekel, the son of the famous avant-garde artist, and Oleg Romanov, today's president of Architects Union of Saint Petersburg. Still a little later on, there came the time of private architectural companies appearing here and there, and in 1988 I started an architectural studio of my own. - Can you name the milestones in your company's career? - Probably, our most active period falls on the 2000's when there was a surge of development activity. Our first major success came in 1999 when we built "Corona" complex in Moscow. If compared to the Saint Petersburg practice of those days, it was the most complex set of problems that we were to solve - the underground parking garage, and lots of other different functions new by the standards of those days. By degrees, are team grew both in its size and professionally. In 2002, "Tsytsin Architects" launched a joint company in Moscow - "MonArchAMC"; in 2008 - "Tsytsin and Biktashev Architects"; in 2009 - "TsB2" (Tsytsin and the Balskys). Handling large-scale projects, I at one point realized that architects and designers alone are just not enough. For this reason, we have human resources of our own for each branch of work that we do. Today, our company has about a hundred employees. "Korona" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin Architects"Korona" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin Architects- Your catalogue names the top priorities of your company as effectiveness, poise, and harmony as a projection of the Vitruvius triad on the realities of today. What does the classic category of beauty mean to you? Does it have an absolute or relative nature? And is there is a place for it in today's world? - Of course, there is a deep connection between "Tsytsin triad" (smiles) and Vitruvius triad. "Beauty will save the world", as Dostoevsky once said. Hegel (following in the footsteps of Plato) claimed that "beauty in art is the emanation of the Absolute or Truth through an object". Of course, in our era of postmodernism and total pluralism with its all-pervading relevance, the absolute categories are hard to find. Nonetheless, beauty - whether coming from God or man-made - is still a manifestation of the timeless divine world. - What are your main creative principles? - First of all, this is contextual thinking. Your building must be in the right kind of relationship with both man-made and natural environment. We must try and learn to hear this music of our spaces: the rhythms, the styles, the scale relationship between the buildings and their independent elements. If you fail to exactly meet these parameters, your project is not worth building. Your stylistic situation may vary from one location to another: say, in a city's historical center modern architecture can also be quite appropriate, just as a historical stylization. As an example, I can mention our project that was built on the Maly Avenue of Saint Petersburg's Vasilyevsky Island - this is quite a contemporary building but it fits in with its context thanks to its size, the stucco technique, and a few other elements. I think that imitating historical styles with the techniques of today and modern materials is really the wrong thing to do. It is perfectly ok to base your work on contrast - everything depends on the specific situation. "Fjord" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin Architects"Fjord" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsWhat really matters to me is the continuity of the space, the connection between the interior and the exterior (I am a member of the Artists Union of Russia), with the surrounding landscape. This includes your volumes, façades, parks, lighting, and whatnot. Your design must be integrated, pervading all the levels of the space that you work with, and, still more importantly, possessing both current and eternal meanings. It plays a role that's both symbolic and informational. This is why our task is a double or even triple one: on the one side, we must try and understand our customer as best we can and meet his specific requirements, and, on the other side, we must broadcast in our work some eternal laws of beauty, at the same time reflecting our time in it. - What are the main challenges that you as an architect get to deal with? - Well, there are lots of them, and each one of them must be addressed together with its related issues. - One of the main issues in our profession is the fact that we as architects have virtually no rights. This is a huge loss not only for the people that will live in houses that we build but for our investors as well. When an investor starts dictating his terms he does not understand that ultimately it is he who is missing out, and what kind of quality of living environment we could have provided otherwise. And it's not even always a matter of price, even though, well, most of the time it is. However, if you do your math right you will see clearly that extra investment will increase the attractiveness of your future project so much that you will be sure to get a great return on investment. Second of all, while in the early perestroika we had too much freedom, then now it's a kickback - there's too much bureaucratic hurdles on all levels. Meaning - there's nothing wrong with rules and regulations, they must be there but they must not be a "barrier" but a "crutch" or even a "springboard" for both architect and investor. Now this system is building insurmountable barriers, while the process of design itself turns into a racecourse (or labyrinth) with obstacles and traps. Yet another issue is the high interest rates in this country. And when the interest rates are this high, the investor cannot have a goal other than building something real quick and then get off this merry-go-round just as quick. As a rule, he is not interested either in quality environment or in effective operation thereof. "Krestovski Palace" residential building © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsResidential building on the Vasilyevsky Island "Fjord" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsResidential building on the Vasilyevsky Island "Fjord" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsResidential building on the Vasilyevsky Island "Fjord" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin Architects- This fall you became a member of "Ekos" - a new town-planning section of the Architects Union of Saint Petersburg, the body that develops the proposals on improving the quality of the town-planning policy. What does this work mean to you? - During the early perestroika, we all had the illusion that "the invisible hand of the market" would effectively regulate the town-planning processes. Time has proved, however, that this was a huge and dangerous mistake. In reality, the manifestation of the free will must go together with strategic planning and organizing your priorities. And it is the job of the government to create the conditions under which the developers can invest, build, and thus make a positive difference to our life. In other words, the developers' interests must be channeled to meet the overall interest of the city. Unfortunately, today the federal and local authorities lost, to a large degree, the powers of regulating the developers' actions. Changing this situation would be an extremely difficult thing to do - all the more so because the direction was set all wrong. We are trying to make what contribution we can into the cause of making a positive difference to this situation. - What would you wish for yourself? - Stable work, understanding customers, and a well-coordinated team. A project is definitely something that depends on team work, so, a great team with hand-picked and carefully grown members is critical for your successful work. H@ of ZAO "Baltiyskaya Zhemchuzhina"("Baltic Gem")© Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsResidential complex on the Krestovka River © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsResidential complex on the Krestovka River © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsProject of "Yuntolovo" residential area © Sergey Tsytsin ArchitectsProject of "Yuntolovo" residential area © Sergey Tsytsin Architects"Platinum" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin Architects"Platinum" residential complex © Sergey Tsytsin Architects"Avant-Garde" Hockey Academy © Sergey Tsytsin Architects"Avangard" Hockey Academy © Sergey Tsytsin Architects |

|