|

We continue the publication of a series of the interviews intended for the catalogue of Russian pavilion XI Venetian biennial. We remind that in a pavilion exposition participate 16 Russian architects and 10 foreigners who build in Russia. One of them – Norman Foster, whose bureau Foster+Partners conducts seven projects in Russia at the moment

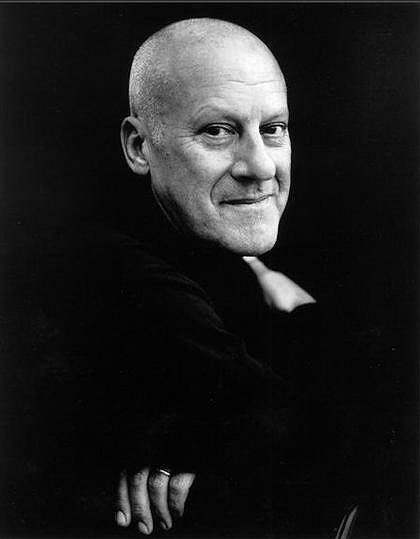

Lord Norman Foster was born in 1935 in Stockport, Manchester, to a working-class family. He graduated from Manchester University School of Architecture and then won a scholarship to study at Yale University. In 1963, he co-founded Team 4 with Richard Rogers and in 1967, he established his own firm. Early on, he developed the concept of a rapidly constructed, lightweight, prefabricated building envelope with integrated structure and services and a highly adaptable interior. His high-tech buildings are informed by the structure, logic and beauty of bridges and machinery. Foster and Partners employs 1,050 architects in London and over 200 in other offices in twenty-two countries. In 1990, Norman Foster was knighted and in 1999, he was honored with the title Lord Foster of Thames Bank. The same year, he became the 21st Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate. His firm has realized hundreds of projects, including the Wembley

Stadium renovation, the Great Court at the British Museum, the Millennium Bridge in London, the Commerzbank Headquarters in Frankfurt, the Reichstag renovation in Berlin, the Millau Viaduct in Southern France and the world’s biggest airport in Beijing.

Currently, the office has seven projects in Russia, including the 118-story Russia Tower; the Pushkin State Museum

of Fine Arts extension; and several mixeduse developments including Crystal Island in Moscow and New Holland in

St. Petersburg.

We met at the Foster and Partners studio at Battersea, on the South bank of the River Thames, which is an examplary

living urban village. The architect’s family occupies the full penthouse floor, which sits atop the three lower floors of his

design studio and five intermediate floors of apartments. Visitors are encouraged to spend time at the in-house café where

the architects congregate at breakfast or lunch time. The entry into the main second floor studio is marked by a huge image

of the Russia Tower, a large model of the Geodesic dome by Buckminster Fuller and many dozens of other models stacked

from floor to ceiling on adjustable shelves. One of them is a wood model of central London with about 20 miniature buildings made of white Plexiglas, representing realized projects by Foster and Partners. Our conversation took place at an open mezzanine overlooking a full floor doubleheight space were 200 architects work with a spectacular view over the Thames, crisscrossed by motor and sailboats.

How did you first discover architecture?

At school, art was one of my favorite subjects. Since I was twelve, I was interested in drawing, painting and the history of architecture. As a kid, whenever I was cycling out of Manchester I would go to see the radio telescope at Jodrell Bank Observatory. At the age of sixteen, I worked at Manchester Town Hall, which was a fantastic building. During my lunch

hour, I would walk to see the Daily Express Building or the Rylands Library, which was one of the first public buildings in

Manchester to incorporate electric lighting or glass, as well as the steel Barton shopping arcade, which was inspired by the

Galleria in Milan. I also discovered another aspect of architecture through the public library where I read books on Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. For example, “Towards New Architecture”, which was recently republished, I discovered there. However, I never made the connection between being interested in architecture and studying architecture or becoming an architect. That came much later, when I was 21. By then I had done enough research to make the connection. By that time, I had already completed two years of national service in the Royal Air Forces as a radar technician, two years in the treasury department of Manchester Town Hall, and studies of bookkeeping and commercial law in College—so I was a late starter in the world of architecture. Also, I couldn’t get a grant so I had to raise the money to fund my studies. But, I think it was a good experience for me to study and work at the same time.

After college in Manchester you won a scholarship to study at Yale University. What was that experience like?

I won a scholarship to study in America and I could choose between Yale and Harvard. At that time Yale was arguably

better because of a combination of great professors there – Paul Rudolf, Vincent Scully and Serge Chermayeff, who was, of course, Russian.

How did Scully, Rudolph and Chermayeff influence your education?

They were all complementary. Paul Rudolf was an action man. Reputedly, he did working drawings for his office designs over a single weekend and I can believe it. So, when he came around for a critique at the design studio, if a student didn’t have any drawings or models to show there was no conversation. Serge Chermayeff was highly intellectual and a pure conversationalist. You could have all the visuals but he wanted to know why you were doing your project.Dialogue and theoretical discourse were more important than the drawings. And Vincent Scully was very insightful about history and observation. He had an extraordinary objectivity and was a very penetrating critic. He could talk about Seven Samurai in a local movie theater or what Eero Saarinen was working on in his studio nearby. Between projects he always encouraged us to visit important buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright and others. So for me it was a combination of the action of Rudolf (which was very powerful because I think architecture is about building), the intellectual research of Chermayeff and the historical insights of Scully. I believe everybody in my studio has an extraordinary level of energy and can-do mentality, which is woven through a genuine belief in the value of research and historical awareness. So, Yale University is a very valuable model for the physicality of this office in the sense that it is also a 24-hours-a-day and sevendays-a-week place.

How did you meet Buckminster Fuller and what did you learn from him during your many years of your collaboration?

He came to England in 1971 to design the Samuel Beckett Theatre project in Oxford and he wanted a collaborator. A mutual friend set up a lunch and we met in the Arts Club near Trafalgar Square. I prepared my office to receive him and everybody was very excited. At the end of this lunch I said, “I would like to show you my office.” He asked why and I said, “because you are looking for a collaborator and I would like to try to persuade you“ And he said, “Oh no, no, you are the collaborator!” So it was done. Our conversation over lunch was the real interview, which I did not realize at the time. He was really the world’s first green architect and was passionately interested in the issues of ecology and sustainability.

How was he as a person?

He was very provocative – one of those people that if you met him, you would learn something or he would send you away and you would pursue a new line of inquiry, which would later turn out to be of value. And he was totally unlike the stereotype or the caricature that everybody assumed he was like. He was interested in poetry and the spiritual dimensions of works of art. Once I took him to the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, which I designed, and he immediately started to talk about the scale of the objects – little Eskimo sculptures carved out of ivory – and he reflected on the way that they sat very comfortably in this very tall space. We walked through the building, then spent about half an hour outside and then went back in. When we came back through the same entrance he drew everybody’s attention to the way the sun had moved and how it affected the shadows. Then he started asking people how much the building weighed. I had no idea and then when he left I said to my people, “maybe we should find out how much our building weighs. Tell me how much Sainsbury Centre weighs?” And then I started to think and we analyzed how much the building weighs above the ground and below the ground and I sent him a letter with all these numbers. I remember that the huge part above the ground actually weighs a fraction of its very heavy basement. And I think you can draw a lot of interesting design conclusions from this comparison.

So, one of the lessons you learn from Fuller is to ask questions.

Sure. One continuously learns from people and sometimes you learn from an older person and sometimes you learn from a young student. I have a small foundation that awards travel grants for architecture students to explore design ideas. This year we considered a number of proposals and at the end we learned a lot of very interesting things. One proposal was based on what one might learn from slum dwellings in South America. One particular student observed with his camera and sketchbook various ingenious environmental and recycling initiatives. It was a fascinating insight into anonymous design skills and once this student comes back from his travel, we will invite him to give a presentation in front of our entire office, which has become an exciting tradition for us.

Could you talk about the anatomy of your skyscrapers, specifically the Commerzbank in Frankfurt, and how your ideas of vertical villages and the democratization of the workplace are going to translate in the design of Russia Tower?

I think a sequence of projects represent the process of this evolution. The Hong Kong Bank (1979) was the first building

to question the center core model of a skyscraper. I still find it extraordinary that this was the first attempt in the history of

the skyscraper that someone questioned and dissolved the center core and moved it to the edges. This is what Louis Kahn had done in a medical laboratory, which was essentially a low-rise building. So, once you move solid elements to the sides and you had the potentials for voids and the ability to break down uniformity vertically to create interruptions in terms of double-height space, which could then work as refuge floors in the event of a fire. That thought was developed further in the unbuilt Millennium Tower (1989) in Tokyo and then through the Commerce Bank in Frankfurt (1991–1997), which started the spiral organization and the idea of triangulation that was explored in the Barcelona Communication Tower (1988–1992). And then the 14 Spiraling Gardens is next in the sequence because if you join those up and they become the spiral, which is the Swiss Re Tower (2001–2004).

But when you get into a new scale, the aspect ratio of a tower changes. In other words, a pyramid is much more stable than a needle. In a way, the shift in the Moscow Tower was to persuade the client to do a single-phase tower instead of a cluster of three buildings. So, if you put those three buildings together you will get a tower, which is visually wonderfully slim. Its aspect ratio is close to a pyramid, like a tripod, which is incredibly triangularly stable—which brings us back to Buckminster Fuller. Bucky would do this game with a necklace that was all wobbly and you would take one bead away and it would still be wobbly and then you’d take away another and it would still be wobbly and so on and so on. Then, finally, when it came down to three – it went rigid. This was Bucky talking about three-dimensional geometry, triangulation and, of course,

Russia Tower. This structure is based on the same ideas and is inherently rigid. Bucky would try to demonstrate these ideas

with images in nature and so on. Then he would mix the uses that make it an energy efficient mini city. For example, when

one energy demand is declining the other energy demand is ascending—so you have this wonderful synergy of activities and it is very responsive to a climate such as the one in Moscow. The building is not deep and has very good natural ventilation and is very good in terms of natural light penetration. It is also a very flexible building because it is column-free and instead of buying repetitive floor plates, you could buy a volume and shape it according to your needs. So, it is very flexible and very secure.

Originally, you proposed various schemes for the Russia Tower.

There was a dialogue with the mayor and the relationship with my client is very creative. There was a lot of debate, a lot of research, and finally, there was a consensus and now the tower is under construction. It will take four to five years to build it.

You said: “My mission is to create a structure that is sensitive to the culture and climate of its place.” How is the cultural aspect achieved in Russia Tower and what was the main inspiration for its tapering profile?

The skyline of Moscow is very specific. There is a lot of wedding cake architecture of the Stalinist period and the early churches are all quite pointed on the skyline. So I think the Tower also rises in that direction and is of that spirit; it is a tall

building in an area that is designated for very tall buildings, which is not unusual. There is La Défense in Paris, Canary Wharf

in London, Battery Park City in New York...

Did the Constructivists influence your Russia Tower design decisions?

I think a number of architects have been touched by Constructivists and I am one of them. When I was a student at Yale, I spent time socially with Naum Gabo, who lived in Connecticut. And of course, the Tatlin Tower has been a very evocative image not just for me but for my generation. I have been to the Melnikov House and some other great examples in Moscow. Moscow is a city that I enjoy immensely and I think Russia has a tremendous spirit.

In many of your projects, you emphasize technological and ecological features. At what point does the architectural form emerge? For example, what was behind the use of diagonals in the Hearst Tower in New York?

I think one of the many themes in my work is the benefits of triangulation that can make structures rigid with less material. I think in New York, the Hearst Tower gives a kind of urban order. I think the highly repetitive pattern of this tower has a comfortable scale feeling. Buildings like Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Tower break scale with elegant bronze mullions in a different way. In the case of the Hearst Tower, it is a very deliberate contrast with the masonry Art Deco base of the building. I felt this was a good relationship between elements, concepts, styles. Also, the building gives a very strong identity, especially being situated across from Central Park--despite the fact that by New York standards this is a tiny building. So, the symbolic aspect of the building, the technology and the economic use of materials fuse quite well.

Let’s talk about how your office operates and how much do you get involved in designing projects on daily basis.

I am closer to some of the projects than I am to others but I touch them all and they are very close in spirit. Our office is

a cross between the kind of university that I studied at and a kind of global researchbased consultancy. We are structured by a series of individual groups, headed by a design leader. There is a design board and I am a chairman of the design board. So, our office does not depend on one person and the idea is to create an interesting succession model, which will enable the office to go beyond my involvement.

Do you still own your firm?

I have a very substantial shareholding but I don’t own the firm and I don’t want to because the challenge for this company is

to go beyond my life-time. I have a strong interest but I don’t have the dominant interest that I had in the past. A significant

percentage of the ownership is spread through a small group of senior partners who are two generations younger than

myself. There is also an outside investor, who owns a portion of the company and who has a very strong interest in investing

in global infrastructure. Then there is a shareholder group of about 40 partners, who own smaller shares of this company,

so if you join our office as a young man you have the prospect of ownership and some of our shareholders are in their late 20’s.

What are your plans for the future of Foster and Partners?

More of the same! (Laughter) We are interrupted when Foster retreats for a half-hour meeting with Dassault Falcon Jet Corporation, clients for whom Foster and Partners is designing a fleet of 25 of the world’s most advanced business jets. Then Norman Foster joins another half-hour meeting to go over a competition project for the New York Public Library. He comes back promptly as promised in one hour. I am yours for another half hour before my next meeting.

How many projects are you currently working on?

You know, every morning I have meetings from a few minutes to half an hour so in one morning, one way or another, I could easily scan ten projects. So, in a week I could easily scan 50 to 70 projects. And I am probably in three different places around the world in a typical week.

Do you still sketch a lot?

Yes, all the time.

It is said that buildings are only as good as their clients. How would you describe your Russian experience?

Very positively. I have excellent relationships there. There is a tremendous energy and a very healthy impatience to build a new and exciting world.

How different is it to work in Russia from other countries?

I find that there is a great passion in Russia. There are very strong cultural links to theater, music, literature, ballet and architecture. There are really interesting affinities and differences, which make Russia very interesting and exciting. And I think that the reality of my working experience in Russia is very different from the popular perception in Europe or America. I have done a number of projects and have taken part in juries, such as the one for Pulkovo Airport in St. Petersburg. My personal experience is very good. I am involved in presenting projects at a civic level and I am very impressed by the interest and attention to details that is paid by clients and politicians. For example, the new president Dmitry Medvedev is on the board of trusties at the Pushkin Museum. So, there is a very serious interest in projects on a very senior level in society.

Why do you think it is important for foreign architects to build in various places around the world and particularly in Russia?

It is a long-standing tradition. The architectural heritage of most countries is a story of globalization before anyone had

invented the word. Look at any country, such as Britain, America or Russia. Historically, there is huge amount of cross-fertilization by architects, artists and artisans who moved around. Globalization has been going on for hundreds of years and today this healthy tradition continues on a different scale.

Do you think in the future, the size and height of buildings will increase dramatically?

I think if you look at the relationship between cities and sustainability and the energy they consume, the dense and compact cities consume considerably less energy than those cities that sprawl. Traditionally, the most desirable cities are very dense. For example, everybody loves Venice. It has no cars, it is very dense, and it has many public spaces. Or look at this area of London, which is very urban and one of the most dense in the city – Belgravia, Kensington, Chelsea, Mayfair – they are

very dense neighborhoods. They are also the most desirable and the most expensive real estate. There are no individual gardens but there are very nice parks and squares. So, I think the tendency will continue to be to build very compact and dense cities, whether there is a culture of high-rise buildings or not. Surely, denser cities will be more ecologically sustainable and will offer a higher quality of urban life.

What was the inspiration for Crystal Island in Moscow? How is it related to Buckminster Fuller’s 1962 vision of the Geodesic dome over Manhattan?

Wow! You know, I never thought of that analogy… Yes, you’ve made me aware of something: The site was, in a way, a very large industrial wasteland, and the idea of this project is to “green it,” to create a significant public space, to encourage

waterborne traffic and to create a city within a city with a range of cultural, educational, exhibition, and performance facilities, as well as hotels, apartments, offices and shops. The skin of this project is essentially a symbolic, artificial sky

and a kind of timeless form of enclosure rising to 450 meters. The idea of a stick with a drape is timeless. It is like a circus

tent, which is a column-free space. The structure forms a breathable second skin and thermal buffer for the main building,

shielding the interior spaces from Moscow’s extreme summer and winter climates. This skin will seal itself in winter to minimize heat losses, and open in summer so that the interior can be cooled naturally. It is a paradigm of compact, mixed-use, sustainable city planning, with an innovative energy strategy, and when completed it will be the largest single building in the world.

Do you anticipate similar structures to be designed in other parts of the world?

It is a microcosm, of course, but there will be only one Crystal City. I don’t see it as a franchise. But, there will be more

developments in that direction—more dense mixed-use developments under one roof.

Could you comment on your project called Orange in Moscow?

The concept there is multifaceted. The idea is to create a kind of arts quarter for cultural events similar to Arts Basel. It is

about creating a potential for a destination with a significant amount of public space that will bring important cultural activities. The project is still at a very early conceptual stage.

Why is it called “Orange”?

I don’t think it was that serious a connection. It was about looking at structures in nature and the way in which you could create segments and at one point, somebody made an analogy to the orange. I think this segmentation idea will develop

but the concept is about a fusion of art, museum and other commercial activities.

Was the theme of an orange suggested by the client?

Inspirations can come from many directions and we are very open, but we are the architects and we are in the driving seat.

What is your vision of a modern city in 50 or 100 years from now?

Most cities have evolved over time and the instant cities that are created in a flash are the exception. They tend to be symbolic like Washington D. C., Chandigarh, Brasilia or Canberra. Most cities have spontaneous settlements that develop on very different models and they are layered with time. Whether we have other prospect instant cities in our future is an interesting thought. I think so, and I think they will be typified and will become the most progressive examples through a fusion of holistic design – a bit like our own design for Masdar City, which is a new six million square meter sustainable carbon neutral and zero waste community for the Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company. I think what is fascinating about Masdar is that we have been designing it simultaneously with the transport system, which has not been invented yet. So we are inventing the transport system. If you can imagine, you will be able to call up your vehicle on your mobile phone and within three minutes walk you will have your private driverless zero-pollution car that will take you to your destination via the shortest possible route. So, if it is an instant city as opposed to a traditional city that will continue to be retrofitted then it will take advantage of very advanced transportation systems. Also, it will be very pedestrian. There are 15 billion dollars being invested in this city already. It is already under construction and it will be finished in 2018. With expansion carefully planned, the surrounding land will contain wind, photovoltaic farms, research fields, and plantations, so that the city will

be entirely self-sustaining. New cities are a very exciting prospect and the future will present a combination of instant cities like Masdar and retrofitted historical cities like London, New York and Moscow. None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

|