|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 30.03.2015 | |

|

Wayward Architecture |

|

|

Sergey Khachaturov |

|

|

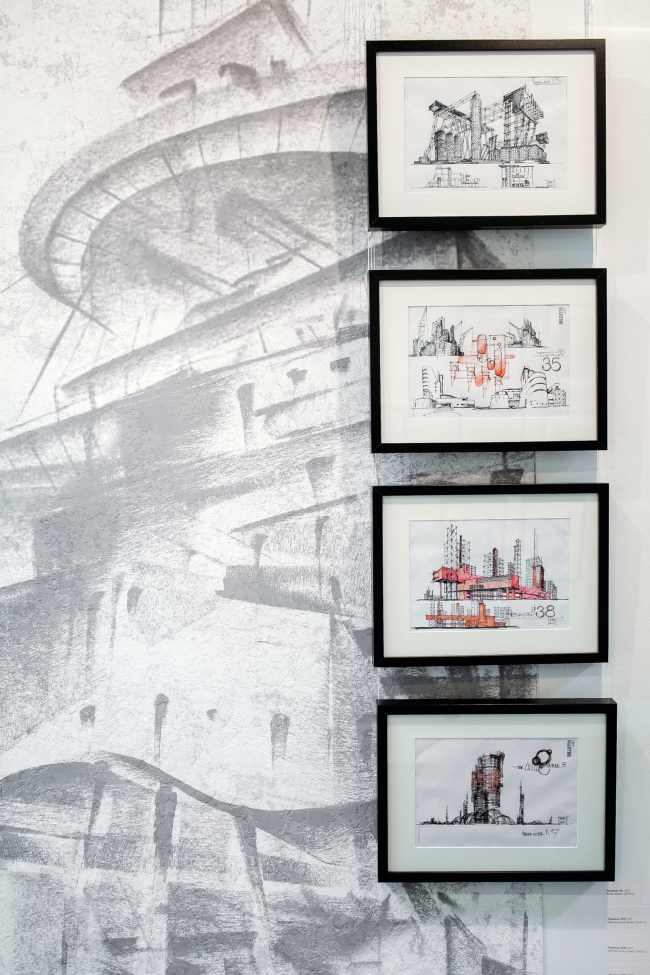

Sergey Khachaturov on "Estrin Code" exhibition. Presently, Moscow's gallery "A3" is hosting the exhibition entitled "Estrin Code". Its subtitle is "everything you wanted to know about the architect but were shy to ask". The curator of the exhibition is a young art expert Anastasia Dokuchaeva. Together with Sergey Estrin, she chose for exhibiting mostly graphic works done in different techniques and materials, and she was right to do so. "Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry RudnikThe small halls of the cozy gallery give you an impression that you have found yourself inside a folder with architectural drawings of various epochs. Only one does not carefully lay them out on the table barely breathing but, creasing their edges, pours the sheets into the folder, really fast, achieving the "cartoon" effect. The animation effect of the restless, shifty, and wanton architecture is truly amazing. Sergey Estrin is a great practicing architect and a true virtuoso when it comes to graphics. He can draw scherzo and capriccio ON anything and WITH anything really. When you look at his towers, bridges, arches, and vaults executed in magic markers, charcoal, pencils, ballpoint pen, and gold leafy technique on paper, Plexiglas, corrugated cardboard, kraftpaper, and tracing paper - you get a feeling that the entire history of architecture is rustling before you, miraculously come alive and spinning in a passionate dance. Quite symbolic is the fact that "Estrin Code" exhibition takes place almost concurrently to the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts' "Paper Architecture. The End of History". At Estrin's example you realize that the three decades of "paper architecture" movement (its main ideologist Yuri Avvakumov considers its starting point to be the 1st of August, 1984, when the editorial office of "Yunost" ("Youth") magazine hosted an exhibition entitled "Paper Architecture") - you realize that these three decades are not at all "the end" of its history but indeed the height of its golden age. If we are to think of the key figures of the soviet and post-soviet "paperists" (Brodsky, Utkin, Avvakumov, Belov, Fillipov, and Zosimov), what brings Estrin close to them is the virtuoso theme development, the whetted project thinking and the love of the quotation-based postmodernist discourse. For example, the very title and subtitle of the exposition already ring the bells of hidden quotes to the two fashionable movies that are quoted literally everywhere to become a recognizable designer brand. On the essential level, the postmodernist connotations of Sergey Estrin's drawings are quite convincing. "Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry Rudnik"Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry Rudnik"Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry Rudnik"Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry RudnikOf course, it is great that the graphic culture of both the "paperists" in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and Sergey Estrin's works can be traced back to the decorators of the baroque theater (Valeriani, the Bibien family, and Gonzaga). Their feather-drawn major and minor scherzos with their colonnades, palace enfilades, and dark underground vaults legitimize the genre of "panarchitecture" that rules out the traditional division into "baroque", "neoclassic" and "premodern". This theater empire is, of course, ruled by Giovanni Batista Piranesi who doubtlessly had a great influence on Estrin. In one ballpoint pen picture of 2011 he even plays at imitating (forgive me my movie-quoting again) of dark-toned velvet strokes of Piranesian etchings. Piranesi was probably the first person in architectural graphics who made us believe that the very invention of a grand-scale edifice is at times more valuable than its implementation, and the play of mind (capriccio) is the art goal in itself, without even the means that justify it or that may be justified by it. His engraved world, sometimes unintelligible but still highly appreciated by his contemporaries, bravely and mightily legalized architecture's right to live by the laws of all arts at once. Not only the art of building (this was pretty self-evident) but also by the laws of music, poetry, theater, and even filmmaking (it was not by chance that Eisenstein wrote about Piranesi). This was the world where the cyclopian structures of the awe-inspiring edifices were at once the scene and the artists of the great extravaganza performance staged by Her Majesty Architecture. Just like Piranesi in the novel by Prince Odoevsky, Sergey Estrin builds a bridge through the centuries, making a direct contact from the XVIII century to the visionary of the epoch of avant-garde Jacob Chernikhov with his graphic capriccios. In his compositions, Jacob Chernikhov explored the possibilities of being sensitive in terms of inventing new avant-garde shapes and forms. Having no fear of getting labeled for eclecticism, Chernikhov introduced into his constructivist industrial spaces fragments and shapes of "traditional" architecture, inscribing the themes of baroque palaces into the multistory skyscrapers. Sergey Estrin even has sheets entitled "Chernikhov ¹ 35" and "Chernikhov ¹ 38". In these pictures, he turns the avant-garde guru's light sketches into 3D shapes. He shows them when viewed from different angles and turns a sketch into an elaborated project. Such postmodernist "stunts" with amplitude from Piranesi to Chernikhov, involve many a viewer into the orbit of formal metamorphoses. Particularly breathtaking are Sergey Estrin's scherzos dedicated to the architecture of the sci-fi cities of the future. In this case he enters into a dialogue with George Krutikov with his "flying city" concept, and Anton Lavinsky with his "city on plate springs", and El Lisitsky with his "horizontal skyscrapers", and Alexander Labas with his architectural ufology. "Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry Rudnik"Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry Rudnik"Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry Rudnik"Estrin Code" exhibition, 2015 Photo © Dmitry RudnikSergey Estrin's drawings are very musical. In these terms, he continues the tradition of the architectural capriccio invented by one of the founders of the USSR's paper architecture, who lived as many years as Mozart did - 35 - Vyacheslav Petrenko (1947 – 1982). The works by Vyacheslav Petrenko are showcased at the exhibition in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. They are definitely worth seeing in order to understand the similarities and the differences between Sergey Estrin and Vyacheslav Petrenko, the founder of architectural inventions on paper. The similarity lies in the fact that the architecture in their drawings has a lot in common with specifically Mozart's sheet music: light, exquisite, virtuoso, and dancing. The differences, however, lie in the conceptual platforms. In his drawings, Vyacheslav Petrenko (particularly in the mega-project of a sailing center in Tallinn) proposed the philosophical idea of a "universal space" that would be capable of housing and implementing the different themes of "stringing the architectural volumes upon the world's power lines" (quoted from one of the master's notepads). Like many paperists of the eighties, Vyacheslav Petrenko supplied his each sheet with detailed explication in which he defined the showcased architectural space via turning to various philosophical, social, and cultural associations. The perfect constants of the human being were the main theme and the ultimate meaning to him. Sergey Estrin does not go as far as to supply his drawings with verbal explanations. His montage is not about the search for the right solution but about the endless variety together with the possibility of solving the space-and-plastique problems that by default cancel each other out. He is very contemporary. He makes a perfect match for today's digital multimedia world in which universality gave way to the unlimited number of discrete options. His drawings in a sometimes wayward and wanton manner reminds of the Art House movies of the recent years. The symptoms are laid bare before us - the choice is left up to the viewer. Sergey Khachaturov and the curator of the exhibition Anastasia Dokuchaeva © Sophia Remez |

|