|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 24.02.2015 | |

|

Antidote for the Evil |

|

|

Alla Pavlikova |

|

| Studio: | |

| Arch Group | |

|

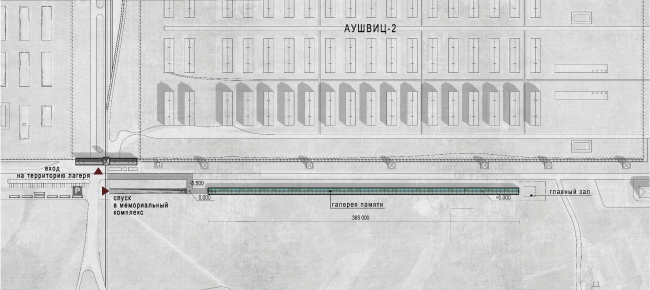

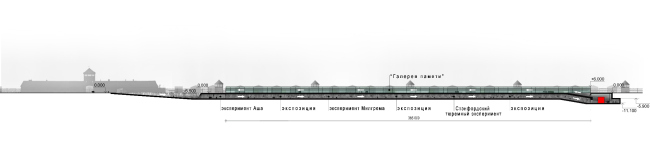

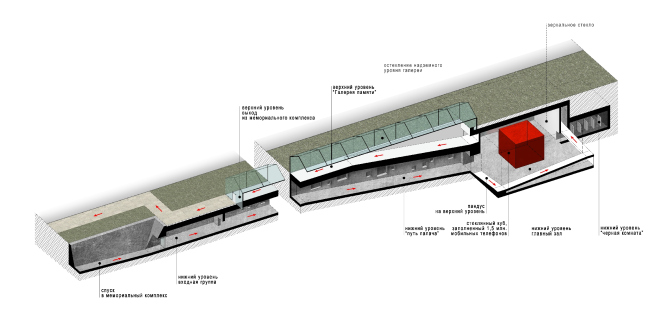

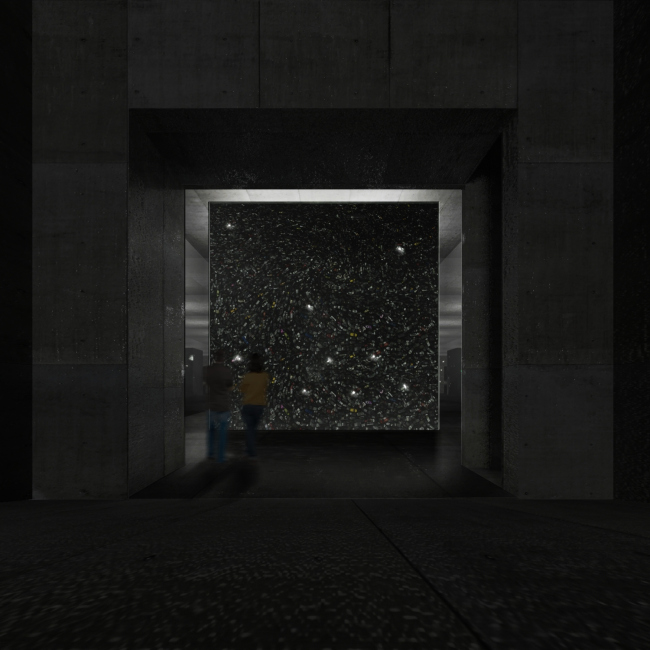

Designing a project of the memorial complex on the territory of the former Auschwitz death camp gave "Arch Group" a pause for thought as to what turns millions of people not only into victims but also into executioners. The architects call this memorial complex on the territory of the former death camp "an anti-evil injection". Auschwitz Memorial Complex © Arch groupThis year will see the 70th anniversary of liberation of Auschwitz. This date will be commemorated, among other things, by the architectural contest that was announced late last year - the contest offered the architects from around the world to propose a concept of a new memorial center. Now in Auschwitz works the museum complex created shortly after the war in 1947 in the surviving barracks of Auschwitz II - Birkenau - that is considered to be the epicenter of all the horrors that went on in the camp; it was there that three quarters of the total number of the camp's victims died (over a million out of a million and four hundred thousand). According to the specifications, the new memorial center is to be situated next to the territory of the former camp Auschwitz I which is now in fact quite a modern center of Oswiecim, a quiet Polish town with a population of some forty thousand people where now nothing is bringing back to memory the events of those years. And, according to the specifications, the future center must include, besides the memorial museum, a lot of public territories and facilities: a large lecture hall, creative workshops, and educational classes. Initially inspired by the idea of designing a museum as such, the leaders of Arch Group Aleksey Goryainov and Mikhail Krymon later on came to a conclusion that the contest specifications in fact divert the participants from the memory of the great tragedy - and signed out from the contest. Without taking part in it, though, the architects still developed their own project of the Auschwitz museum, of a solely memorial nature, developing in this work their own vision of such exposition. Thus, this project that is meant neither for implementation nor even for participation in the contest can be arguably referred to the "paper" category - effectively, it is a conceptual study of the important theme. Auschwitz Memorial Complex. Location plan © Arch groupAuschwitz Memorial Complex. Plan © Arch groupIn their project, Aleksey Goryainov and Mikhail Krymov placed the museum near the walls of Auschwitz II death camp that is now part of the existing complex. The architects stretched the galleries of their museum in a thin thread running along the road that leads to the camp, hiding the main museum space underground so as not to distract the visitors' attention from the camp itself with its long fences and menacing barracks. It is only the top gallery that is visible above the ground. It is completely made of glass but has the shape of a barrack and thus fits in with the surrounding scenery. Auschwitz Memorial Complex. Section view © Arch groupAuschwitz Memorial Complex. Section view © Arch group"Anti-evil" injection - this is the name that the architects gave to their project, offering, as they put it, to reconsider the very essence of all the traditional holocaust museums. As a rule, these museums include the appropriate human records and photographs of the victims; terrified, each visitor involuntarily puts himself into the victim's place in his mind. Psychologically, visiting such museums leaves the visitors depressed and terrified. Not everybody can withstand watching even a small part of these expositions. Mikhail Krymov explains: "The victim does not choose its destiny. Its different with executioners. People turn into them of their own free will, consciously, sometimes without even noticing that they've passed the point of no return. In such places, it is not considered appropriate to speak of executioners but, let's face it, in some certain circumstances, any visitor of this museum can find himself not only in the place of the victim but also in the place of an executioner. The documentary portrayal of the events of those days and of the process that turns ordinary harmless people into the perpetrators of these crimes can hopefully prevent new atrocities". The psychological research that was done after the war, as well as recently, successfully proves one of the long-known truths: there is evil in every one of us. For example, in Asch's psychology experiments, 75% of the participants gave an incorrect answer to at least one question if that incorrect answer was backed by the majority of the group. In Milgram experiments, 87,5% of the group "killed" the victim by electricity guided solely by the authority of the scientists. In Stanford "prison" experiment, the students that got the roles of the prison security guards, in two days started showing sadistic traits and inclinations. These experiments were repeated in different countries and proved indisputably the universality of their results. "I am sure that if the participants of the experiment had been told what the experiment was all about in advance, and then asked to repeat the whole thing over again, the share of those who were ready to fulfill the order would have been significantly smaller - says Aleksey Goryainov - And it is the mitigation of these appalling numbers, the antidote against the evil, against accepting it and submitting to it, that must become, in our opinion, the main mission of this museum/memorial complex". Auschwitz Memorial Complex. "Executioner's Progress" © Arch groupThe realization of the fact that the visitors are in for facing a terrible reality comes already at the entrance situated next to the main gate of the camp. The museum entrance group is a gray concrete tunnel going underground. Collapsing into a tiny dot at the end, the long narrow gallery has no natural light in it. The overall length of this oppressive corridor is about 400 meters but the visitor is not offered any other path to go, so everybody who is coming must follow this route. The architects treat it as a kind of purgatory passing through which no one will ever be the same again. Meanwhile, as a matter of fact, apart from the oppressing atmosphere, the corridor does not have in it any terrible documents about the victims of Auschwitz or any details that can frighten or scare the visitors away, cause repugnance or kill the desire to think about the events of those days. The underground corridor is the "executioner's progress" that depicts the life of ordinary people. The surviving documents and photographs allow for creating such an exposition from beginning to end: here is a person that lives in a nice little house, he listens to music, plants flowers, gets his education, raises his kids and achieves his share of success. At some moment, there appear the documents of him signing in for the Nazi party, and about his job promotion. Bit by bit, this person becomes a part of a huge machine that crushes everything in its way. Then there is a war, Auschwitz, and an endless nightmare of dead bodies. Thus, in front of the visitor's eyes, unfold the lives of the executioners including those moments where they could have stopped but for some reason or other did not do so. The exposition is now and then interrupted by installations displaying the results of the psychological experiments described above - reminding the people about the danger of becoming a part of the evil cause. The visitor gets involved in this process taking a number of simple tests developed by professional psychologists - these tests vividly demonstrate how easy it is to manipulate people and set them on the path of violence. Auschwitz Memorial Complex. Monument to the martyrs of the camp © Arch groupHaving gone the whole way, the visitor finds himself in a large mirror hall in the center of which a large six-meter glass cube is installed, filled up to the brim with... mobile telephones! According to the authors, there must be a million and a half of them - which corresponds to the approximate number of people killed in the camp (the exact figure is still unknown). The authors deliberately use this contemporary object as opposed to the real things displayed in the Auschwitz museum - the glasses, toothbrushes, and shaving brushes that the fascist guards wrenched from the prisoners. A mobile phone, something that nowadays everybody has and uses, becomes the link to the present day - it seems to be saying that even today the humanity is not guaranteed against a repetition of this tragedy. The multitude of glittering screens is meant to help the visitors to get the idea of the magnitude of what happened here, multiplying manifold in the countless mirror reflections. The cube is a monument to all the victims of Auschwitz, and its reflections are the memory of all the instances of genocide. Auschwitz Memorial Complex. Mirror Hall © Arch groupThe mirror hall is circled by a ramp that leads back up to the ground surface where, under a glass dome, the architects organize the "Memory Gallery" in commemoration of the victims of the camp. The main "exhibit" of the gallery is the camp itself whose terrifying panorama spreads before the visitors eyes full-scale: the machine-gun towers, the barbed-wire fences, the first line of the barracks where hundreds of thousands of people were held captive, the spots of the foundations, and the forest of incinerator chimneys looming against the sky. It is here that one gets the sense of the reality of the tragedy about which the underground exposition shares, the physical contact with it. The glass wall of the gallery that is opposite to the camp bears the surviving registers and photos of the prisoners. Most of those who got killed were not even registered anywhere - they were thrown in the gas chambers right after they were brought to Auschwitz. The authors of the project decided to honor their memory in the endless rows of small, three cm tall, human silhouettes. This is yet another attempt to help the people of today to get the idea of the atrocities that were done here. Leaving "Memory Gallery", the visitor again finds himself before the main gate of Auschwitz II, from where the guided tour over the territory of the real camp might start. Auschwitz Memorial Complex. Memory Gallery © Arch groupA special part of the exposition is the room named "Black Hall", also underground, behind the mirror hall. It shows the traditional exposition of Holocaust museums that depicts all the horrors of the death camp. This room is deliberately organized in the form of a separate block as an indispensable but still not mandatory part of the exposition. The visitor will decide for himself or herself whether he or she wants to visit that room and take their children along who quite possibly will be shocked by what they are about to see. Here it is very important to make sure that the visitors do not get a sense of repulsion in respect to the pictures of the starving skeleton-like prisoners - that usually keeps the museum visitors from treating them as real people. Repulsion and aversion are natural protective human reactions; they block the empathy center and a number of other sympathetic feelings. All the fascist regimes used this cruel device to foster hatred for this or that "enemy" people by stopping calling a human a human and thus creating a moral justification base for their crimes and atrocities. "We do not want the visitor to stop for a minute seeing real people either in the executioners or in their victims. Both of them were people - conclude the authors - We would want the museum to evoke the right emotion so that, after visiting it, the person would get the right experience, however hard or unpleasant, but still making him a better person". The experience of designing such a museum, even without going beyond the pale of the conceptual meditation into the sphere of real-life design is, of course, very important, as is the experience of studying the limits to which the human psychology can be bent, twisted, or manipulated, and its helplessness in the face of the almighty propaganda that easily finds and awakes a beast virtually in any human being, a beast that is ready to go and search for the enemies judging by the signs and traits that someone else thrust on him. This theme is acutely painful to the point of intolerable - but all the more relevant. At which exact point do we become accomplices to murder? When do we do the first concession against our conscience for the sake of career, success, and well-being? How solvable at all are the problems of mass psychology and, more importantly, is the "antidote for the evil" described by the authors possible? Can the recurrent disease of blind hate be cured once and for all? Probably no one can answer these questions. But the attempts to cure this disease are still worth trying. |

|