|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 09.02.2015 | |

|

Color of Memory |

|

|

Anna Martovitskaya |

|

| Studio: | |

| SPEECH | |

|

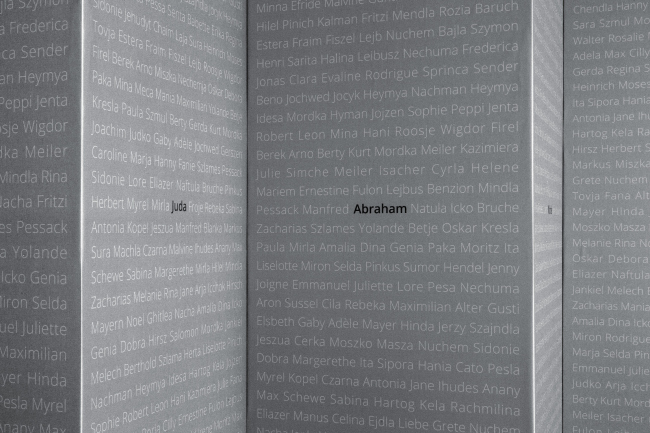

The expo space of the Jan Vanriet exhibition called "Losing Face" was designed by Sergey Tchoban and Agnia Sterligova. The exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition that has been open since January 27 in the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center is in fact part of the project "Man and Catastrophe" organized in commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz death camp prisoners. For Jan Vanriet, on of the most popular painters of today's Belgium, this theme has a deeply personal aspect to it: a lot of the members of his family were political prisoners back in the day. Specifically, the artist's mother and uncle went through the concentration camps as members of the Resistance movement. And, while the young girl was able to survive, her twin brother died soon after his liberation from the camp: in memory of him, there are but a few photos left, and a family legend how he as a boy loved to play his accordion. For the painter, the image of his mother's brother forever fused with that musical instrument - one of Jan Vanriet's most famous paintings is the "Uncle's Portrait" with an accordion instead of a face. The accordion’s bellows have faceless barrack windows "installed" into it, a stairway trodden upon by thousands of feet, and a chimney with the thick smoke issuing from it and leaving no hope whatsoever. Now this canvas can be seen in Moscow, and for the authors of the exposition - Sergey Tchoban and Agnia Sterligova - it became the starting point in developing the design concept of the exhibition. The exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe forty portrait paintings are part of the grand-size series "Losing Face" that Jan Vanriet created based upon the "protocol" snapshots of the prisoners - the portraits are placed within a blind introvert volume the inside walls of which are painted dark-gray while the outside walls are laced with the names of the victims of Kazerne Dossin. Most of the names are inscribed in light-gray, and only some of the names are highlighted in a darker font - the architects' message is clear - the catastrophe claimed the lives of millions of people and only bits and pieces of information of some of them are left. The exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovOn the plan, the exposition has a trapeze shape - its sides are fan-folded, the "bellows" streaming to the narrow base with "Uncle's Portrait", making this painting the pivoting point of the entire exposition. Still, though, the compositional solution had yet another, just as meaningful, prototype to it: "The plan of the "Bakhmetyev Garage" in which the Jewish Museum is situated, is based on a similar "comb" principle, and for us it was extremely important to pay tribute to Konstantin Melnikov's architecture with our project" - says Sergey Tchoban. The exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila Remizov"Besides, such a shape is the perfect means to enhance the perspective, and it is also an incredibly exciting technique of exhibiting the paintings - continues the architect - On entering the hall, the visitor is first of all subliminally intrigued by the central painting, while catching only glimpses of the ones that hang on the sides. However, as one progresses along further down the hall, the portraits gradually open up, and when one finds himself in the middle of the installation, all these faces are looking straight at you, each telling their own tragic story". The authors also found the optimum height of the walls - the four-meter-tall partitions completely isolate the exhibition from the rest of the museum, enhancing manifold the effect of immersion into the story told by Jan Vanriet. The exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe final chord that is also, probably, the most crushing in terms of producing an emotional impression is the two children's portraits that the architects placed at the rear side of the hall that they created. These are a lot more sizable canvases (1x2 meters, all the other adult portraits being 40х50 cm), and they clearly dominate the exposition. While all the adult prisoners' faces are ultimately the colorized black-and-white "head-against-a-white-background" photos, these two boys are portrayed full-length. One of them - Hermann, at most five years old - is a cute child whose parents brought him to a photo studio, sat him down on a chair, and gave him a toy to hold. It is only the absence of any adults around him (and, from looking at the painting one gets an unmistakable feeling that they were initially there in the photograph) - can drop into this idyllic picture a spark of alarm. The other one is his age mate Samuel - and his portrait was also painted from a photo from day-to-day life, only it shows a little prisoner of a death camp. The difference between the two children is obvious to the visitor at first sight, within a split second, and this split second covers the abyss lying between life and life one step away from death. The exhibition "Losing Face" will be open until March 1 2015. The exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila RemizovThe exhibition "Losing Face" by Jan Vanriet. Photo: Danila Remizov |

|