|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 04.02.2015 | |

|

Sunstroke: Avant-garde of the XXI Century |

|

|

Alla Pavlikova |

|

| Studio: | |

| Ostozhenka Bureau | |

|

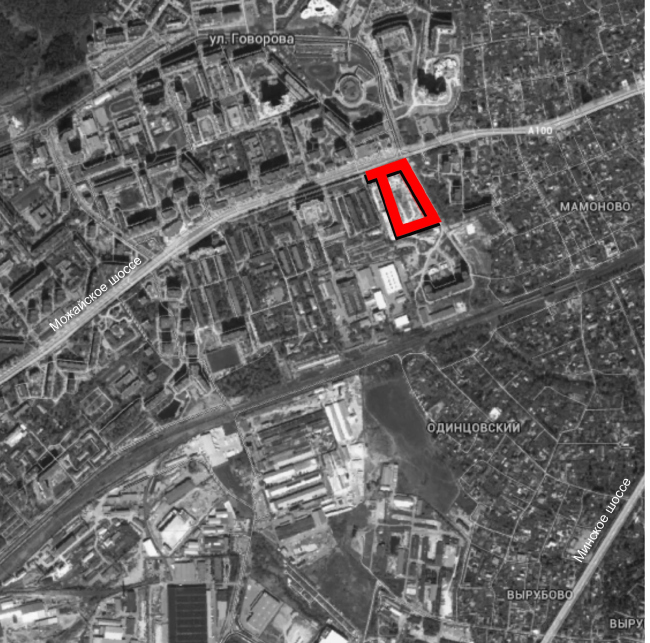

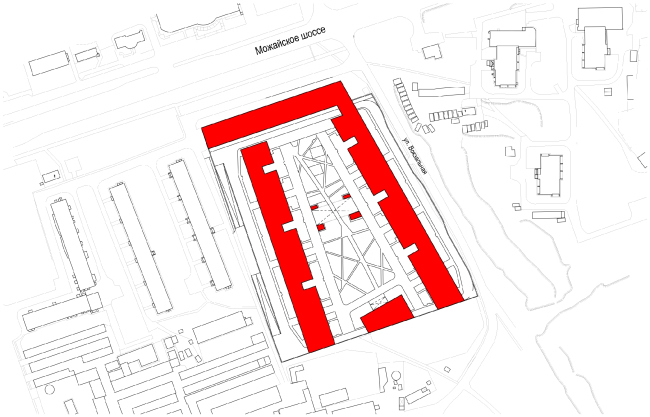

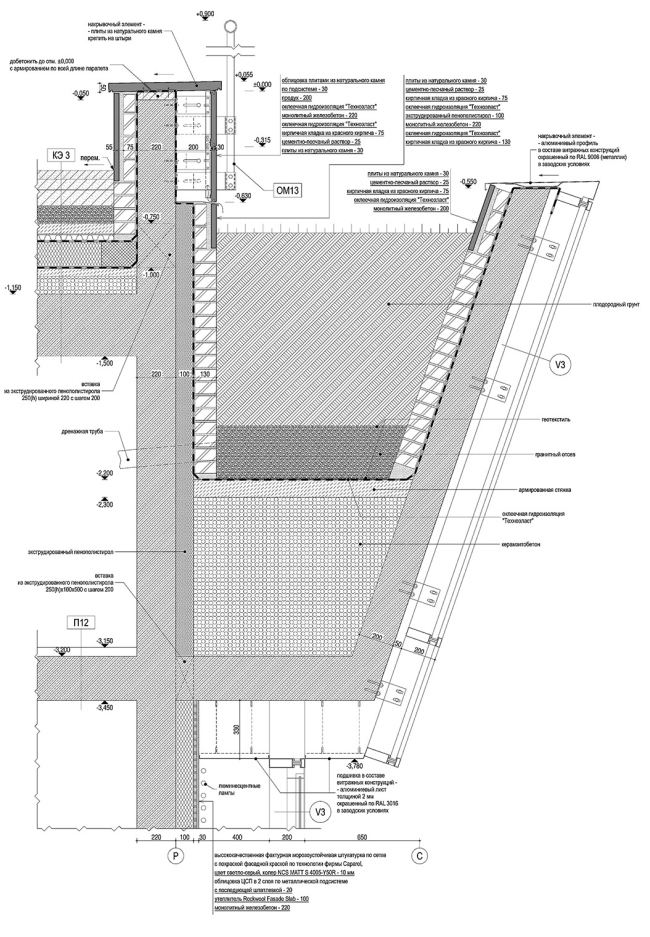

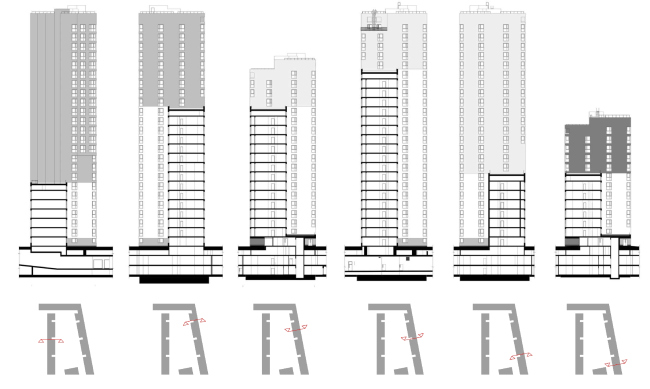

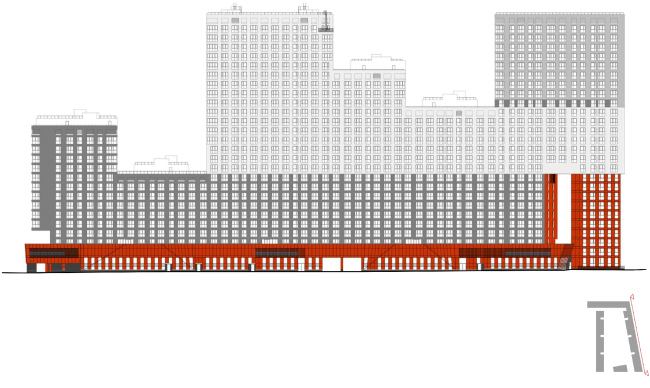

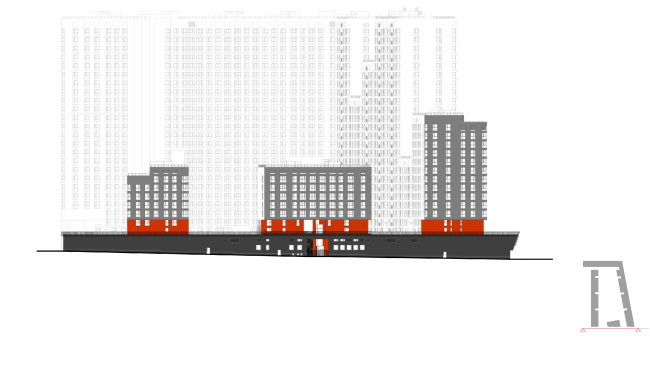

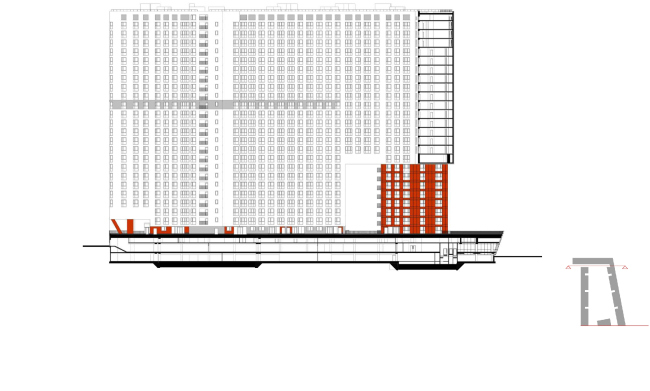

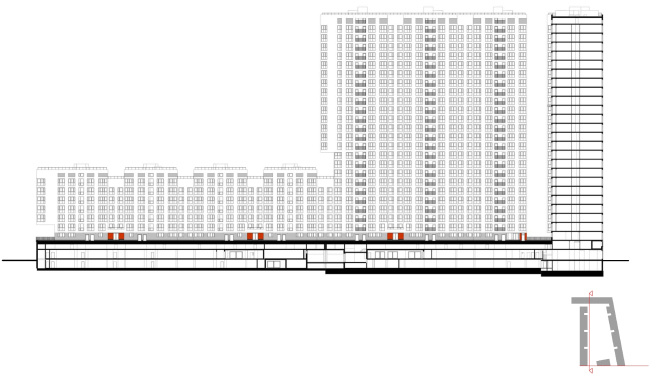

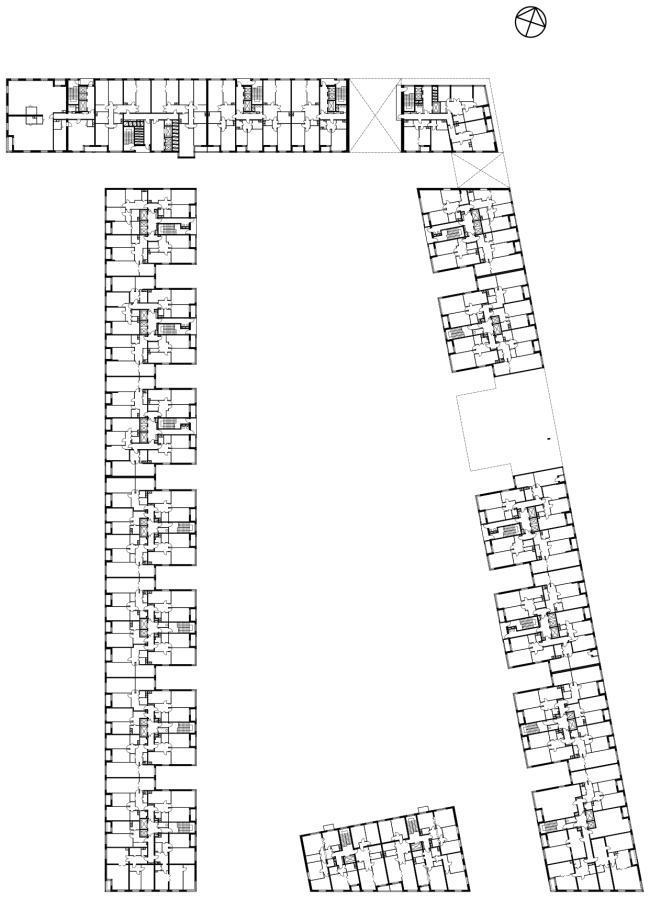

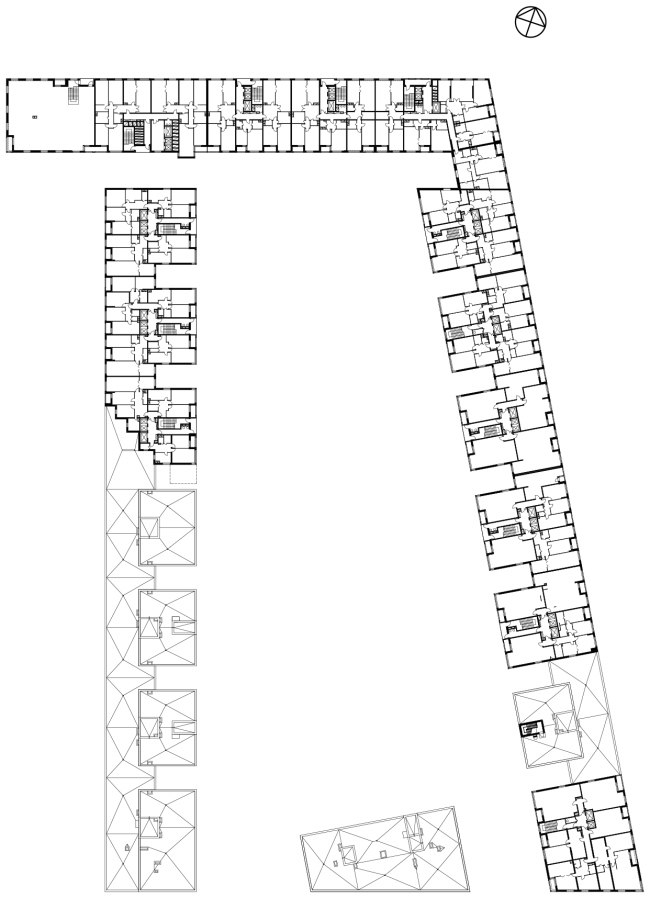

A daring plastic play with the volume of a giant multi-apartment complex just outside of Moscow: a sophisticated silhouette, impressive views and a beautiful-looking reminder of the fact that avant-garde is our all. NoneThe story of the residential complex in Moscow's suburb of Odintsovo started simultaneously with the story of the complex "Water Colors" in Balashikha - during the crisis of 2008. It was at that time that "Tekta" company thought nothing of launching two large-scale projects at once, turning to "Ostozhenka" Bureau. Today, both complexes have been successfully put into operation, and, furthermore, got several honorable mentions as the model residential projects that meet all the requirements of forming a quality urban environment. Just one example: at Arch Moscow 2014, they both were short-listed as the most relevant projects for the quarter construction and development in Russia. In both cases, the architects were required to build, on a limited land plot, a residential complex of impressive dimensions. "The main thing to remember while doing such projects is not to indulge in any kind of excesses - says Alexander Skokan - Our work was all about making the giant building look appropriate in its place using various techniques: arches, color spots, work with scale and silhouette... These are compositional and plastic techniques, the building does not grow any smaller just because of them but you still can get interesting visual effects that help liven up the boredom of the contemporary construction. I think that the yard space of the Odintsovo complex turned out to be interesting and even exciting specifically thanks to its giant arches". The land plot on which the house has been built is in fact the territory of a former motor pool located at the driveway from Moscow to Odintsovo, to the left of the Mozhaisk Highway where the scattered private cottages give way to residential high-rises. The place was suggestive of creating here a prominent building, an “entrance” landmark of sorts, outstanding and memorable, signifying the change from the village to the city scale. NoneFrom the standpoint of planning techniques, the project follows the principles of quarterly development - so it is not surprising that it represented the so-recently-popular genre at Arch Moscow. Raised on a single stylobate one level above the ground, the three units "embrace" the trapeze-shaped land plot along its perimeter. One of them, the longest, marks the borders from the northeast and from the northwest, forming almost a right angle along the Vokzalnaya Street and the Mozhaisk Highway. The second - stands like an impregnable bastion on the western border of the plot. The third building, the most compact one, occupies the south position leaving wide passages that lead to the landscaped yard organized upon the stylobate. NoneNoneNoneNoneWhat is interesting is the fact that the yard here is of a two-level kind - not a yard, really, but a curious vertical structure: the upper one, green and quiet, spreads on the roof of the stylobate, while the busy upper one, with a whole system of driveways and streets, one piercing the whole complex from bed to end, hides inside. This solution helped to significantly save up the territory that was initially, as usual, barely enough for the construction of such a large residential complex. Besides, by raising the yard one floor up in the air, the architects were able to make it almost completely vehicle-free, providing only the fire lanes stretching along the outer side of the complex - under the beautiful cantilevers. NoneNoneWith the rather simple and laconic planning, the first thing that catches one's eye when looking at the complex is its incredibly sophisticated silhouette with a height drop from five to seven floors. The authors say that these height drops are their response to the requirement to observe the insolation norms and provide the necessary amount of light for the people living in the new complex and for the people from the neighboring houses. It seems to me that this is false modesty, though: coming up and drawing in detail a sophisticated silhouette is always more difficult and time-consuming than finding a simple and efficient solution with the help of an insolation ruler superimposed upon the master plan. In this case, however, the insolation ruler was not the ultimate means but one of the designing instruments. As a result, in the part where the land plot borders closely on the residential five-story buildings, the height of the new complex drops down to seven floors. From the direction of the Vokzalnaya Street, where, at some distance from the construction site, three twelve-story buildings are situated, the border of the complex is formed by a jagged stepping block whose skyline follows the sun rays so as not to be on the neighbors' light. The authors also found a way to provide the necessary amount of light for the apartments inside of the yard. Obviously, the decrease in the number of floors considerably influenced the end output of square meters. The loss was to be made up for: this is how the idea to play around with the typology of the apartments. We already wrote about the "Ostozhenka" architects dealing with a similar challenge when building "Water Colors" residential complex. In this case, a slightly different solution was found: in order to squeeze the required amount of square footage into the given dimensions, the architects took the buildings that marked the boundaries of the complex, and stretched them up to twenty-two meters as opposed to the regular sixteen. This was possible thanks to the deep vertical niches that at large intervals pierce the volumes of the buildings all along the length of the complex. Around the niches, the architects placed the kitchens whose windows overlook the yard, while the living rooms and the bedrooms get the maximum amount of ambient light. Apart from the interesting typological solution and the necessary "square footage output", the architects were able to come up with a very attractive image of the inside-the-yard facades. Thanks to the deep cutaway niches, the yard-oriented facades turned into a semblance of slender towers of different height that form fractured and variously-scaled development that is really human-proportionate. The rhythm of the pattern formed by the walls, together with the different heights of the volumes, makes the complex look like a giant church organ or maybe some rocky mountain. Especially beautiful and robust the complex looks in the rays in the setting sun when its slanting rays - one of the main instruments of shape-building, they really do a great "carving" sculptural job here - cast long shadows on the walls of the complex, and the whole things stats looking pretty sci-fi. In a word, a "sunstroke", as the authors who highly appreciate the meaning of the sunlight in making their architecture complete aptly called it. NoneNoneNoneHowever, it was not the sun that the architects were inspired by, or, rather, not the sun alone. The whole image of the complex vividly shows its creators' love for the Russian avant-garde tradition. This can be seen both from the usual "constructivist" colors - gray, white, red, and crimson - and by the thought-out work with the form where particular attention is paid not only to the substance but to the void as well. Giant "chunks" of the body of the building get simply taken out of it, like, for example, the cantilevers overhanging above the fire lanes or the already-mentioned vertical niches. Also, the substance-and-void vocabulary of constructivism gives birth to the opening that appears between the northwest and northeast buildings, through which, like through a ravine, the rays of the setting sun penetrate into the yard. Another sunstroke, to be sure. The most outstanding element in this array of voids, however, is the huge arch that pierces one of the buildings from end to end and opens up a magnificent view of the Mozhaisk Highway, the town's main transport artery. A corner of the twenty-five story building ominously overhangs in the air. As for its support, it is provided, in the classic tradition of Russian avant-garde, by the bright-red volume placed inside this giant arch (also painted red). A red parallelepiped inside a red cube! This "red leg" in fact functions as the landmark of the entrance of the city - bright and memorable. "...Based on the architectural experience of the 1920's, and using their lexicon, we tried to revise this territory in our own unique way - shares Rais Baishev - For the language of architecture, painting, and sculpture, air is oftentimes more important than substance is. Hence the huge cantilevers and the giant arch that leaves the complex devoid of at least fifteen fully-fledged apartments, and the "slit" between two buildings, the one that gives you the feeling of space". The street facades that correspond not to the human, but already to the city scale, are designed in a different way. Here, the smooth and uninterrupted surfaces of the walls are devoid of any plastics whatsoever. The "fractured" feel of one's perception of it is only provided by the stepping silhouette and the color solution that let the architects prevent the volume from looking too big or too bulky. The opaque but still saturated gray color of the crowning part of the complex blends with the tones of the overcast leaden sky. As for the main body of the building that is "tied up" to the skyline of the surrounding houses, it was designed unobtrusive white. Thus, the facade looks as if a strict horizon line was drawn upon it: everything that is below it belongs to the city, everything that is above - to the sky. The desire to soften the volume and make it proportionate not only to humans but also to the environment shoes in details. For example, to conceal the massiveness of the main volumes, the architects came up with corner windows - and the pieces of glass look as if they were "embracing" the corners of the building. And this is yet another curtsy to the ideas of Bauhaus and Russian constructivism. Very large, floor-to-ceiling and equal in their size square glass apertures set the general rhythm for the entire complex, and, besides, create extra possibilities for developing one's interior design ideas. The entire necessary social infrastructure is situated in the stylobate whose plastic and color solution is perceived not from distant vantage points but when one comes close to it. On the level of the first floor, as an offset to the flat vertical forms of the residential units, the facade of the non-residential part is designed in as plastic a manner as possible. Executed from colored glass, it reminds a stylized surrealistic river bank, washed out by the whitewater flow or maybe a fragment of rock with bright-red clay loam inserts showing through... And this is now the waterline through which the sun shines "undulating on the water of the broad lakes". NoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNone |

|