|

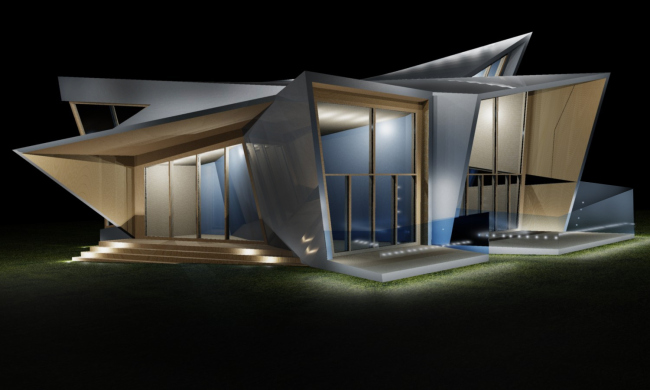

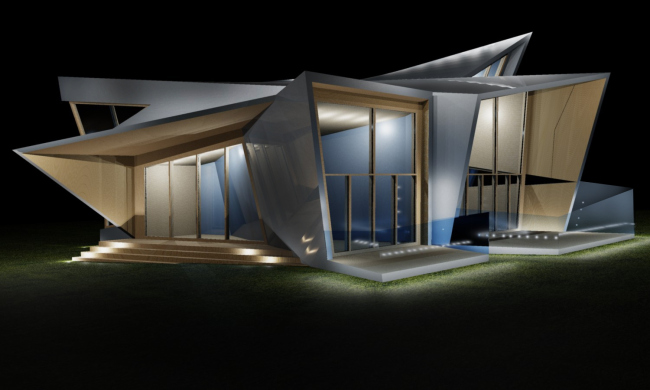

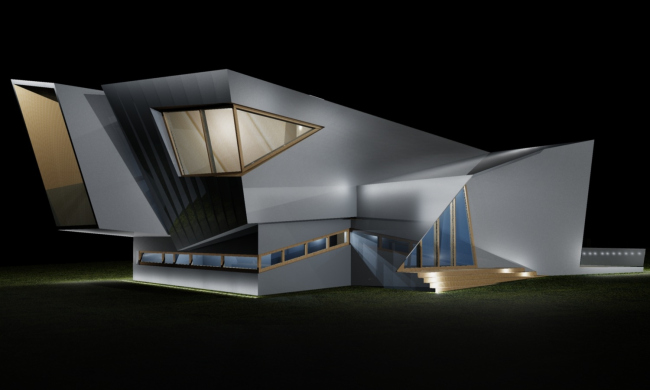

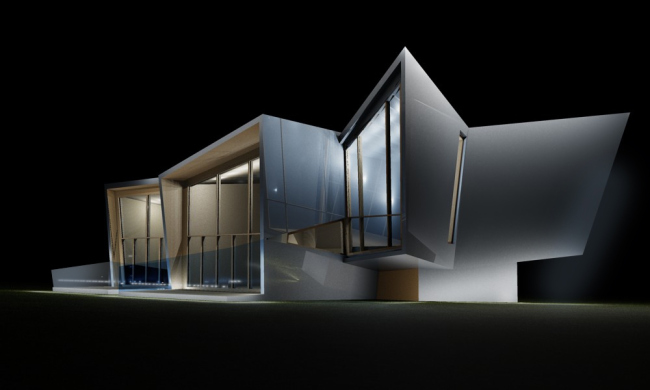

In Moscow vicinity, architect Totan Kuzembaev is going to build a "Crystal" House - a villa with unusual-looking acute-angled facades.

Totan Kuzembaev was

commissioned to design this house by a person in whose opinion the most boring

thing in the world is the geometry of housing that is commonly accepted in

these latitudes. According to him, the rectangular and square plans of

apartments and houses might actually bore a person to death, and he is going to

put a stop to it right now - at least within the confines of his own home. And

it was specifically for this reason that the main condition that the customer

put forward to the architect was the dramatic geometry that promised the villa

as many acute angles and broken facets as possible. Totan Kuzembaev reminisces

that at first he tried to reason with the young man saying that such houses are

more expensive to build, that they are really high-maintenance but then he

checked himself: was this not the opportunity to experiment that every

architect dreams of grabbing a hold of? So, the experiment began.

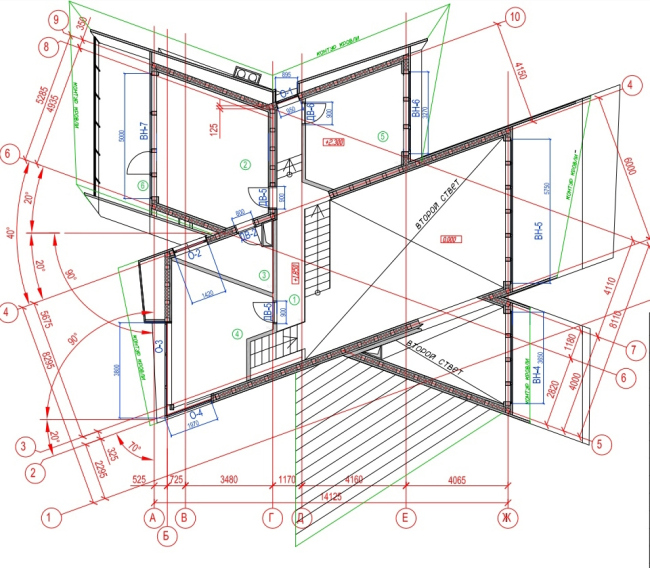

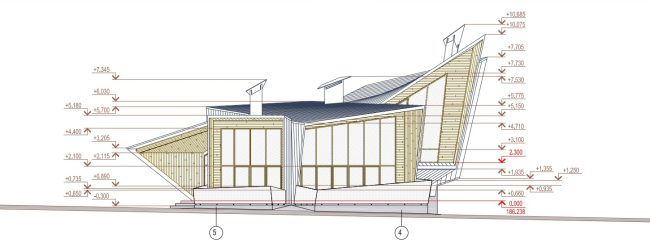

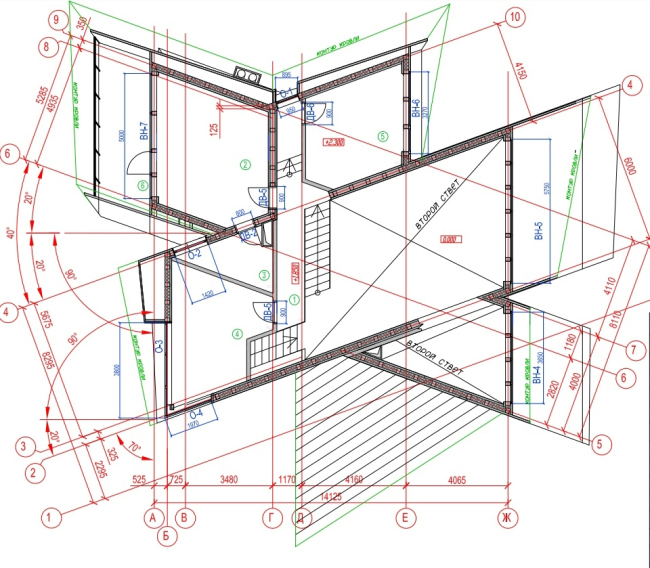

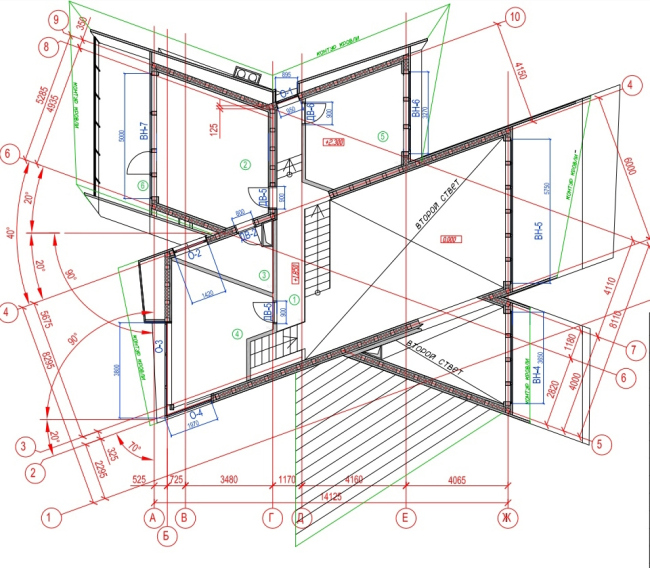

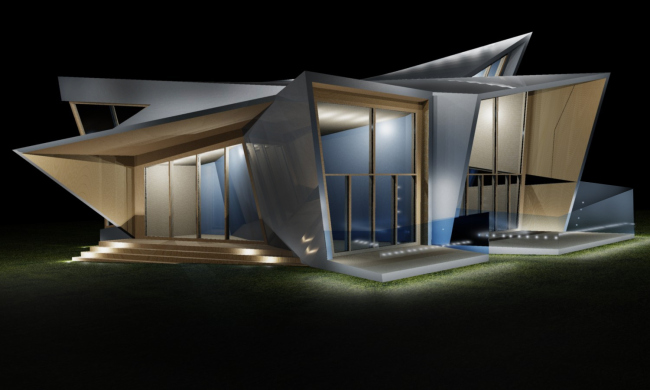

The

customer mentioned his love of triangles so many times that it was this

particular figure that the architect decided to base his plan upon. To be more

precise, on two triangles that cut each other at two sharp angles and then get

shifted a little bit off the central axis. However, even the resulting wild

combination did not look dynamic enough to Totan Kuzembaev in terms of this

particular house, and this is why on its side walls (the short cut-offs of

triangles) the architect makes extra triangular cuts, as if splitting the wall

surface in two, and pierces one of the "open book" side facades with

an extra wedge, thanks to which the plan of the house starts looking a little

like a bifurcating letter "X". Accidentally, it is the bifurcating

side that is actually the main facade of the house that is turned southwest: as

the architect himself explains, he inserted an extra block here so as to turn

"Crystal" to the sunny side with as many of its premises as possible.

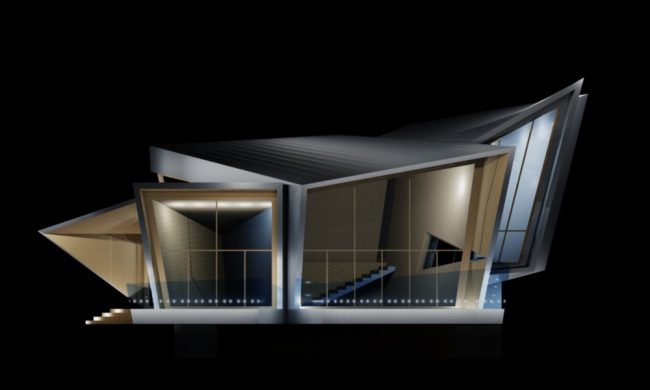

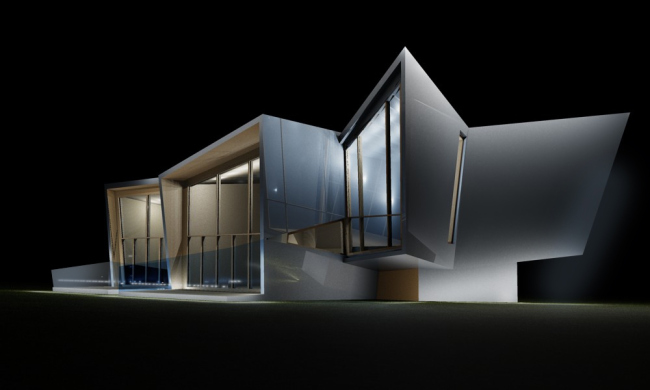

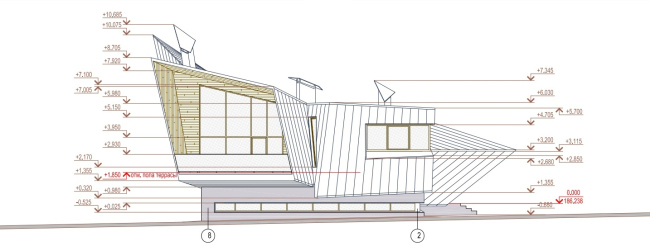

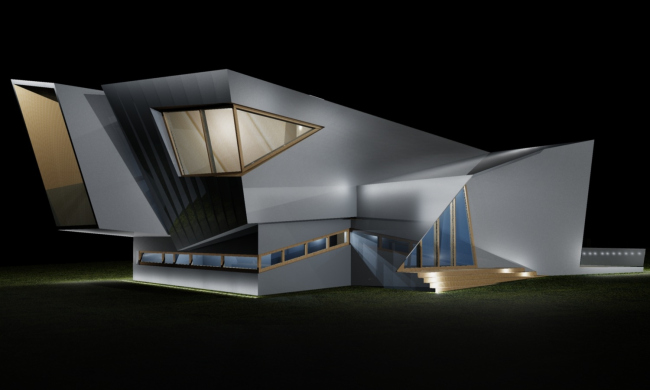

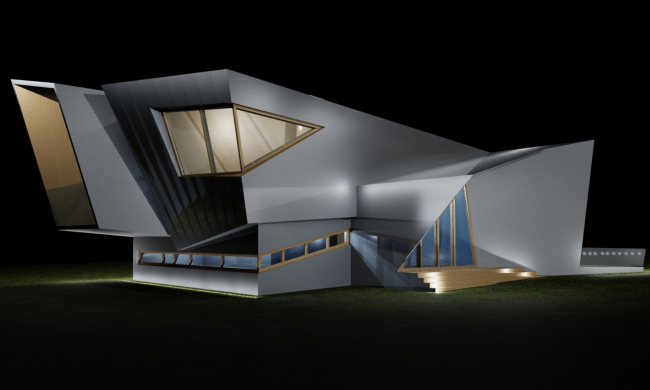

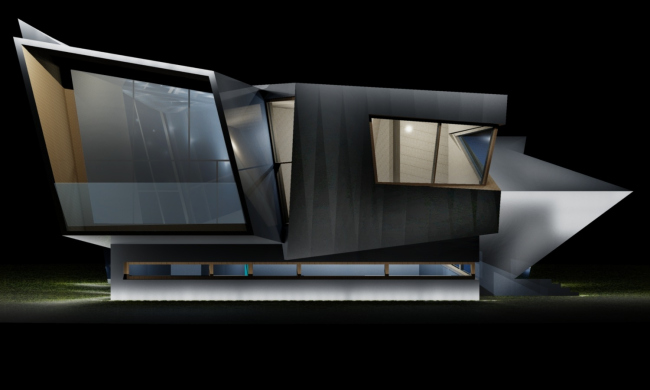

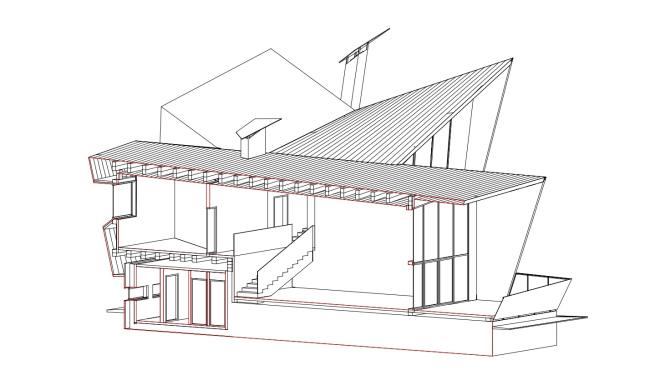

The

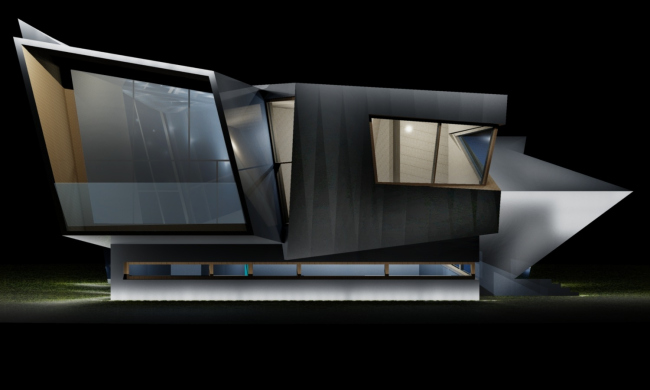

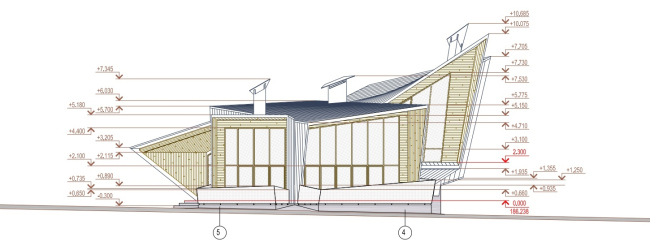

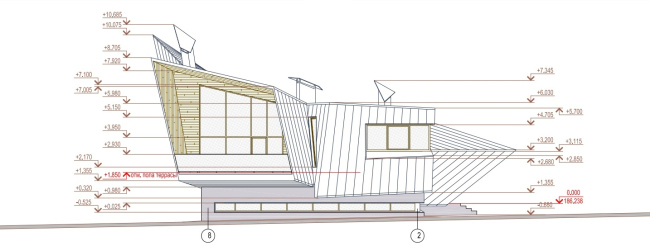

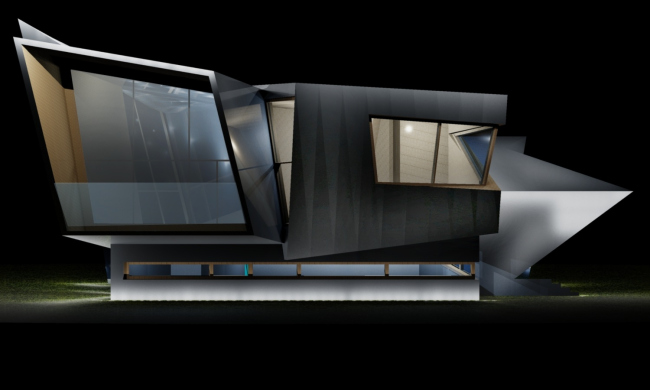

volume that was later on grown matches the plan. The architect treats each

"stroke" of the mysterious letter as an independent volume formed by

broken planes most of which meet one another at sharp angles. For their facing,

Totan Kuzembaev chooses the galvanized roof steel that obliterates the boundary

between the facades and the roof and turned the house into a single crystal structure.

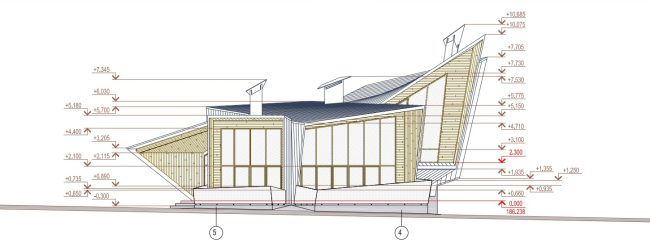

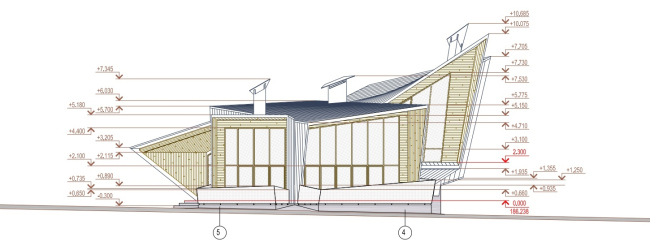

Some of the windows are integrated directly into the facets but the main role

here is played by the panoramic stained glass that completes the broken shapes

and thus softens their terminally dynamic, if not to say hostile, appearance. The

large-scale glazing here can be likened to the polished facets that turn the

mineral into a precious stone.

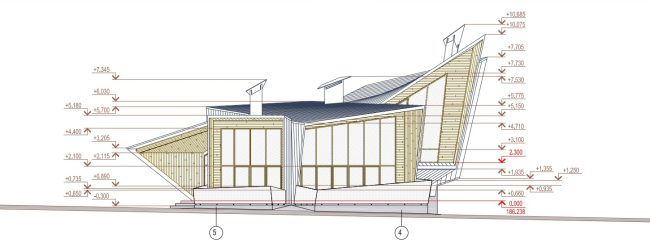

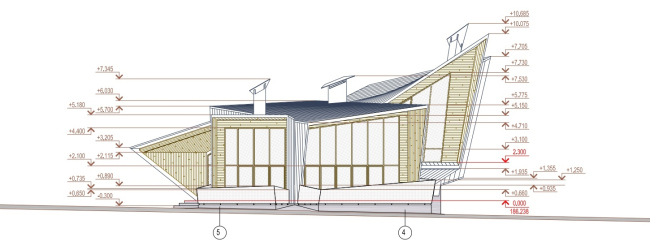

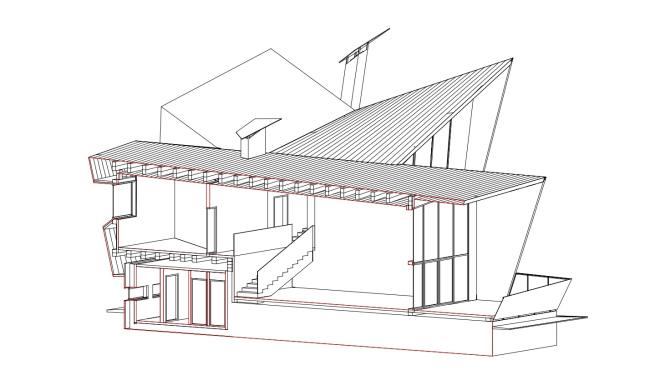

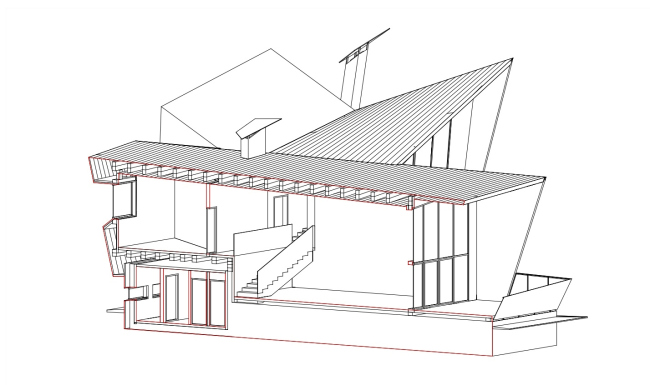

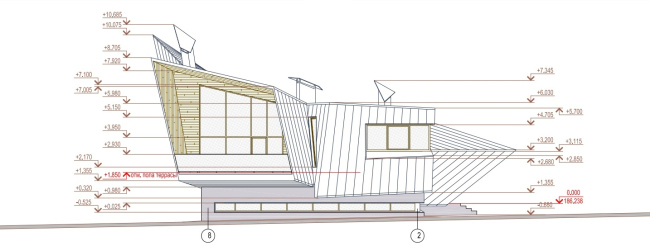

Inscribing

all the premises required by the customer into a house of such a sophisticated

shape proved to be a tall order indeed. The solution was prompted by the small

height difference that was there in the land site: integrating

"Crystal" into the landscape, the architect manages to squeeze into

it as much as four levels. These are not the traditional floors, though, placed

on top of one another, but rather a complex system of double-height rooms,

sunk-in basement floor, and the attic: in fact, Totan Kuzembaev evenly spreads

various functions over Crystal's numerous polygons.

For one, when a person

enters the house he gets immediate access to the drawing room, kitchen/dining

room, or one of the numerous terraces. He can get up half a floor or, the other

way around, down half a floor and see all the utility premises of Crystal. Accordingly,

for the bedroom level a person can get yet another half floor higher up and

find himself in the study - the latter is situated in a separate volume on the

topmost level. According to the author, the unconventional architectural

solution of the house will always show through in its interiors as well. And it

is not just the plans of separate rooms (even though the customer sure will

have to get used to his so-much-craved-for sharp angles) - the walls of the

public areas, for example, will be decorated with the same galvanized steel as

the facades, while the places where this material will not look appropriate

will be reigned by wood - the same kind that is used on the "broken"

slopes of the outer shell of the house.

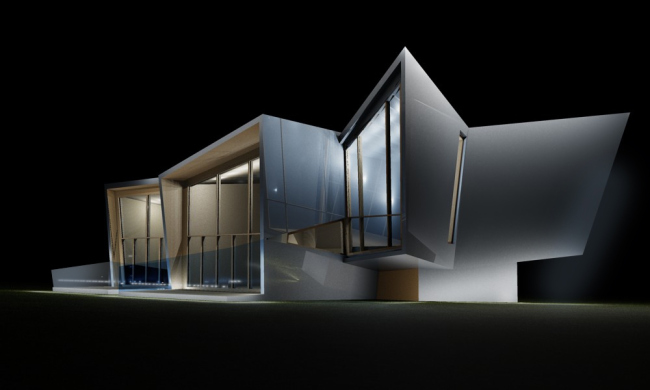

As was

already said, one of the main strong points of "Crystal" is its huge

stained-glass windows that make all its rooms really fair and light. The

utility premises are, of course, no exception - even though they are situated

in the basement floor that is in fact a monolith box, the architect cuts

windows in the m wherever possible. What is also important is the fact that the

relatively narrow band of the openings will not only help the future

inhabitants of the house considerably save on the lighting of the bottom level

but it also plays an important part in the shaping of its architectural image,

visually "lifting" Crystal above the ground, "tearing" it

off the Moscow soil that is not really used to these kind of experiments.

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

|