|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 20.06.2013 | |

|

Øystein Rø: “Colonial model” is the preferred modus operandi of the mineral industry in the High North |

|

|

Nina Frolova |

|

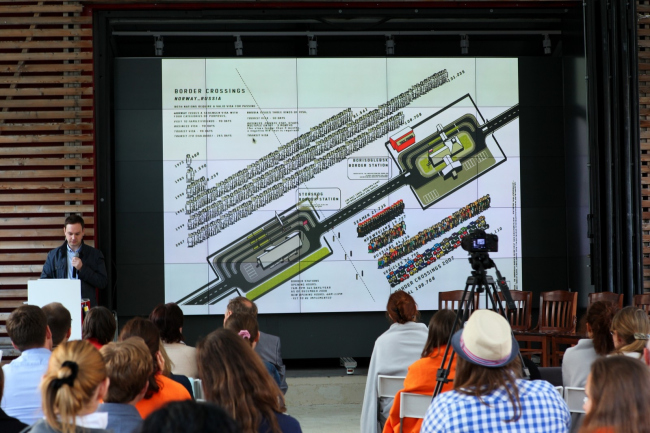

| Studio: | |

| Transborder Studio | |

|

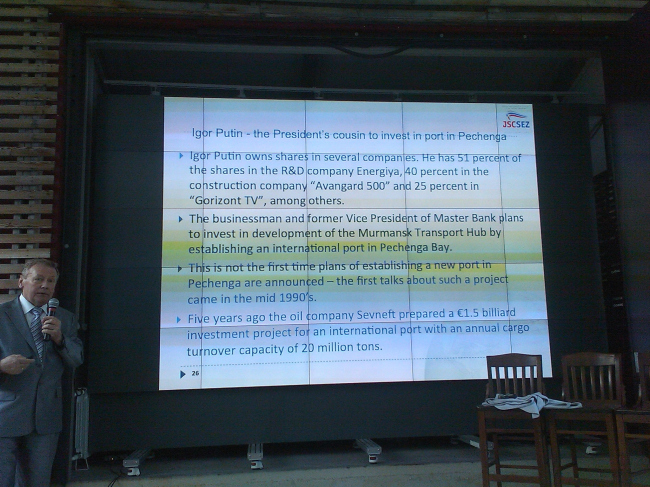

In an interview with Archi.ru, Norwegian architect Øystein Rø discusses future development of Barents Region, new medias for architecture dissemination and comfort as a driving force in creating architecture. Archi.ru: NoneAnd now you are organizing another conference – for Oslo Triennale of Architecture in autumn 2013. What will it be? Ø.R.: It will be part of the project by Rotor from Belgium that curates the main exhibition, they have also laid out a curatorial platform for the Triennale and we are responding to that. The theme of the Triennale is “Behind the Green Door”, it is dedicated to the concept of sustainability – its historical and contemporary meaning and its place in the architectural production. In the conference “The Future of Comfort” we’ll discuss sustainability from the point of view of comfort as a driving force in creating architecture and also the environmental consequences of that eternal search for better comfort, for more luxury. And we want to discuss how architecture can create a more sustainable lifestyle, how we as architects can open up, push, enable people to pursue a lifestyle that doesn’t harm the environment as much as it does today. So we will explore architecture as an enabler for how people live their lives – as frameworks for new ways of living. Archi.ru: In 2009 you published a book on Barents region, Northern Experiments that is based on Barents Urban Survey 2009. What has changed there since then? Ø.R.: I see three important things that have happened in the region after we published our book. The most important thing being the delimitation that ended the border dispute between Russia and Norway (2010). Now the map is laid out and the game can begin, so to speak. Another important event is the establishment of a border pass for local citizens so they may now travel across the border as often as they want. It can really change how people use the border areas. And then you have the Shtokman gas field development, a huge Norwegian-Russian-French collaboration that was predicted to be very important for the future of the Barents sea. It is now terminated, and that is a big change, probably for the better. I think this is a reminder that the world is changing and that the role of this region can too. NoneOn June 7th you took part in the discussion “Pezaniki: Russian-Norwegian neighbourhood” at the Strelka Institute. What was its most interesting topic for you? Ø.R.: For me the most interesting thing was what former consulate in Kirkenes Anatoly Smirnov said about plans for development of a new port in the Pechenga fjord: this means new activities in the borderland, a new reading of the possibilities there. It would be an important step in bringing out the potential of this area. It also represents a demilitarization because now this fjord is controlled by the military. The second interesting topic was the rumor that Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev would present a clean up plan for PechengaNickel chemical plant area (this plant belongs to “Norilsk Nickel“ company and is situated in Nikel settlement). It will be great news if it turns out to be true because this ecological disaster area needs change. Archi.ru: But even if we don’t talk about the ecological disaster and military zone that dampen the development of this region, there are also universal problems of life in the High North. For example, in Polar regions of Canada, in Greenland there are problems with unemployment, high alcoholic consumption and so on. What is the social-economic situation in the Norwegian High North? Ø.R.: For a long time there were problems here too: people, especially young citizens, moved away, but now the situation is changing. The Finnmark county is experiencing a growth of population and SØr-Varanger municipality now has a lot of positions they need new people to take – and people do come there, but even more are still needed. Finnmark still is an area for state support: subsidies, special civic tax system. If you live there, parts of your student loan are paid back to you, there are other financial models that encourage people to reside and do business there. The moment where this won’t be necessary anymore will come sooner rather than later, I think.  NoneThere are mines and other ‘unsustainable’ industries there. What steps has the Norwegian state taken to neutralize their negative influence on the environment? Ø.R.: From my point of view, the state is doing too little, it could be more interested in this problem. There is now a new topic on the agenda – the emergence of new mineral industries in Norway, in Northern Norway in particular. “Colonial model”, the term that Tatiana Bazanova used during our discussion while describing the financial model of Norilsk Nickel’s operations in Pechenga district, seems to be the preferred modus operandi of the mineral industry. I think this is going to be a key topic of the future discussion of the development of the High North. It is very relevant there, in mining industry in particular because these companies do the same thing. They don’t pay a local tax to the municipality, so only people who work in mines pay a tax. But in Kirkenes large shares of the miners don’t actually live there, they work there for a week and then fly back home and pay taxes there. So Kirkenes is basically left with nothing except destroyed nature. It is a type of modern colonialism. It is not sustainable and it should not be a model for the future of mining, at least it should not be in Norway - or in Russia for that matter. In Norway these mining companies invest in the local economy as little as possible. It is a dramatic change in comparison to the situation when Kirkenes was founded around 100 years ago. Then the mining company was responsible for everything: homes, infrastructure, welfare. The town was created by the mining company because it wanted people to live there and have a good life. Now companies reduce their responsibility as much as possible. We led a studio at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design on the emerging mineral industry, not only Norway, but on a global scale, on an industry now venturing into new and unexplored areas on land and even under water: we are witnessing a dramatic and unprecedented quest for minerals that is reshaping the surface of the earth. Archi.ru: If we are talking of the High North as a global region of growth, what could architects do for these areas? Ø.R.: Architects can create models for the urban development, how towns and cities there can be designed. These could be new, better types of cities that bring nature and built environment together harmoniously. It is absolutely necessary given the increasing activity in the High North and the fragility of the nature here. I believe architects can and should be agents for a sustainable development of the High North. NoneNone |

|