|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 04.02.2013 | |

|

A Block White as Snow. On the Embankment. |

|

|

Tatiana Pashintseva |

|

| Architect: | |

| Sergei Tchoban | |

| Sergey Kouznetsov | |

| Studio: | |

| Larta Glass | |

| SPEECH | |

|

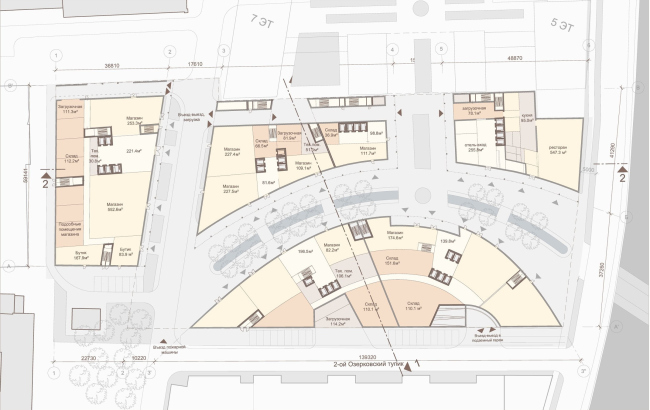

The office complex "Aquamarine" is built on Ozerkovskaya Embankment in the place of the former industrial area; in fact, the architects of "SPEECH Choban&Kuznetsov" came up with a whole new understanding of the town-planning structure of this place. Initially, for the construction of the complex consisting of a few

buildings with offices and apartments, there were allotted two neighboring land

sites stretched perpendicular to Ozerkovskaya embankment. Appreciating the

magnitude of the future construction and its location in the capital's very

center, the architects set before them a task not to limit themselves to

designing an ordinary mixed-use complex but come up with a new typological unit

- "an embankment complex" - that

Ultimately, the construction of the complex was done on the territory

with an area of

The fist floors facing the new street are given to shops, cafes, and

restaurants, and are open to the general public. The planning project specially

provides for making small premises here - under

Three "Aquamarine" buildings are occupied by offices, and the

fourth (and the smallest) one is given away for apartments. Different in sizes

and shapes, the buildings are nevertheless configured similar from the

architectural standpoint - on top of the glass dressing of the facade, a

snow-white grid is placed, whose horizontals are the intermediate floors, and

whose verticals are doubled semi-columns that could remind us of Ivan Fomin

"proletarian classics" - but then again, the authors admit to drawing

inspiration from his architecture. However, while in the 1930's the concrete

columns, devoid of their capitals would stretch up for floors on end, now they

have become part of metal casing of the buildings, rather than the concrete

one. Particularly striking are the rounded corners where the glistening bent

glass, framed with the verticals of double moldings, is crowned with the sharp

triangles of the cornice slabs. The active verticals enrich the plastics, set

the rhythm and make the perspective of the boulevard more dramatic. It is only the largest, fourth, building, whose faced plastics is a

little bit different: with semi-columns the building would have looked too

massive, so the architects came up with a different type of verticals for it,

these being the ribs coming out of the surface of the faced and reminding of

the exploits of the post-war modernism. This solution is justified from the

constructional standpoint as well: this building has curtain walls while in all

the other buildings the walls are of the monolith type. The main entrance is

accentuated by an imposing glass portal, through which one can see the lobby

with an atrium and the "court of honor" turned to the residential

house; above the windows of the first floor, there are glass transom windows in

which billboards and other advertising units will be placed.

The architects were very careful in selecting the materials for the

facades: opting out of trying to imitate the stone surface in composite

material, they looked for metal that would really look exactly like metal. The

white color is meant to enhance the glitter and the lightness, as well as make

the new complex contrast to the surrounding houses and stand out against the

background of stucco and brick facades that prevail at the embankment. It was

also just as important the optimum combination of metallic glitter to keep the

building, as Sergey Choban put it, from "looking like a refrigerator".

This purpose was ideally served by the composite panels Goldstar, lightweight,

and beautifully glittering with subtle shades of color. The architects were

choosing the glass just as carefully. At last they settled on the transparent

glass with a gray tint. The rigorous rhythm of the verticals is especially

prominent against its "mirror" background.

The authors themselves jokingly call their creation "a full-scale

model", and this definition explains both the apparent lightness of the

complex and its ostentatious independence from its architectural context.

Snow-white and modern, "Aquamarine" has not only become a

self-sufficient piece of city architecture but also went a long way to organize

its surroundings.

NoneNone NoneNoneNoneNoneNone NoneNone |

|