|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 10.12.2012 | |

|

The Return of the Project |

|

|

Alla Pavlikova, Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Studio: | |

| Sergey Kisselev & Partners | |

|

Story of the project office and retail building on Kulneva Street (better known under its former name of “Mirax Plaza”) losing its designer supervision, being re-done, and then finally getting back into the hands of its authors to retrieve its architectural integrity. The project of the office

complex “Mirax Plaza” is well known to anyone interested in the contemporary Moscow

(see our article on the 2007 project). Although

after the global financial crisis set in and the main investor left the

project, it lost its proud-sounding name, the two austere prismatic towers

saluting to the  The

previous version of "Mirax-Plaza" project However, as often is the

case, not everything went to plan. The

designer supervision over the construction of part of the “island” (the

building that is turned onto Kutuzov Avenue and that makes up the “nose” of the

oval), was handed over to another architectural office, the project was

changed, and the building was not built the way it had been intended. In a

nutshell, it was generalized and simplified: now there was less stone, more

glass, and the horizontal ribs, while still preserved, became thinner and more

monotonous. The casing blocks, from horizontal and tawny, with “scorch marks”

so characteristic of Stalin times houses, turned into pink-gray and vertical,

now looking very much like “seashell” casing that was used back in the 1970’s

for coating the Soviet movie theaters and office buildings.  The

building on the During the work on the

ten-storey building that in fact makes up the elongated part of the oval

situated next to the Third Transport Ring (designated by the letter

"B" on the various layouts of the complex) it became clear that

keeping its original shape would be impossible due to the recent changes in the

land-use and development rules of the adjacent section of the railroad line.

"While formerly our situation provided the opportunity of placing the

stylobate pillars directly on this railroad section, now the agency for

land-use would not even condescend to considering such a possibility" -

the architects share. In other words, according to the original design, the

volume of Building "B" and the railroad line actually crossed: the

dome-shaped arch of the facade would have overhung the tunnel that pierced the

volume of the building from side to side chordwise but now the building was to

recede into the confines of its construction site.  The original layout The commissioner

announced a tender for the design adjustment of the ten-story building -

naturally, with a view to preserve in the new project the original square

footage with expenses minimized. For the architectural office "Sergey

Kisselev and Partners" this in fact was a chance to retrieve its original

project, and finally bring it to fruition. Knowing their own project inside and

out, the architects quickly found the solution to the problem that was set

before them. The design, of course, underwent a few significant changes (under

the given circumstances it simply could not have been otherwise) but the

authors "did their best to consider the structures that were already

erected and were making all of their planning decisions, if it's possible to

put it like this, in the reconstruction mode". In a word, they only

proposed to make the most necessary changes, at the same time giving back to

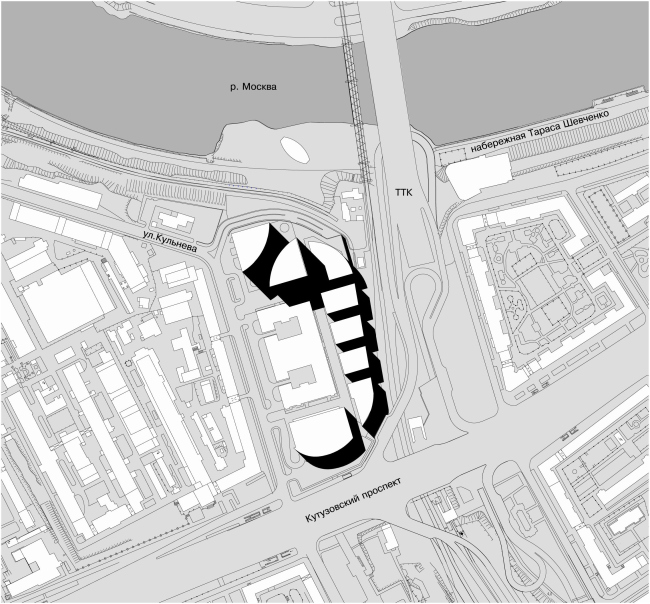

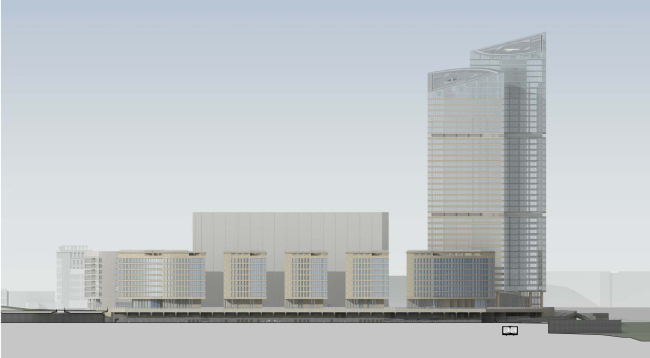

the project all of its original useful space. The regular-shaped, compasses-drawn but protruding too far beyond the confines of the site arch of the oval layout had to get cut off to make room for the railroad line - the layout of the building was no longer a segment and took on the constrained and squeezed shape, like a 1960's TV with straight sides and rounded corners.  Site plan In order to compensate

for the lost useful square footage, the architects divided the elongated

building into five parts, replacing the four atriums with open courtyards. Each

of the five resulting volumes got expanded lengthwise at the expense of

reducing the space of the yards. This measure helped to retrieve all the lost

square meters without increasing the height of the buildings. The yards, in the

meantime, started looking more like short fragments of pedestrian boulevards:

they all lead to the longitudinal inner street that connects all the five

buildings. The latter, at the same time, overhang in deep cantilevers above the

pedestrian space thus winning yet some more useful space and forming small

marquees over the boulevards below.  Visualization. Project of 2012. Version 2. What is peculiar is the

fact that the architects deliberately opted out of making their

"yard" streets car-passable, fully reserving them for the

pedestrians. This resonates a little with a reminder about the cancelled deluxe

atriums - the yards, of course, lack the luxury of their glass surfaces

stretched at a ten-storey height but they still remain the safe and comfortable

space to be in. Unlike the atriums, however, the yards are open to the city and

thus are more democratic: anyone can walk in and around here. This solution is

more on the European than on  The pass-through pedestrian street of Building B The facades, of course,

also had to be remodeled: now they are made up of the same alternating pattern

of horizontal stripes of stone and glass as the towers. At the rounded side

walls the stripes get narrower - here they resonate with the graphics of the

building that stands on the side of the  View from the Third Transport Ring One cannot but be happy

about the fact that the shattered and scattered project got almost unexpectedly

"fixed". This story once again goes to show that a competent

architect will always be able to solve the commissioner's situation as well as

retrieve the all-but-lost project to restore its integrity and find a new image

for it. This "new image" that came as a result of the transformation described, is also worth special mentioning. It is more relaxed, more practical, and more democratic. "Mirax-Plaza", though austere and conceptual, was still dramatic and expensive-looking. It was meant to strike one's imagination with the glass of the atriums, the flying buttresses, and the regular arches and circles. Its architecture sported the contrastive tension: between the concrete and glass, the towers and the avenue (the former being the symbol of the power of money, the latter - the power of the tyrant). The contradictions of the city were aptly reflected in it and turned into a dramatic and powerful story. Which was quite resonant with the times: the period of quick growth, arrogant investors, and giant projects. Now the contrasts are all but erased, the contradictions are softened, and the story is taken to a whole new level: now it has ceased, to a large extent, being a theatrical performance arrested in stone, and has started looking more like the natural history of finding common ground, reasonable economy, and architectural integrity. The complex is stepping back from the obstacle that its predecessor was stepping upon but at the same time it opens its arms and lets itself into the city. These are marks of our times - possibly, just as good as one can think of. NoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNone |

|