|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 14.04.2011 | |

|

Unity in Variety |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Oleg Karlson | |

| Studio: | |

| Karlson & Co | |

|

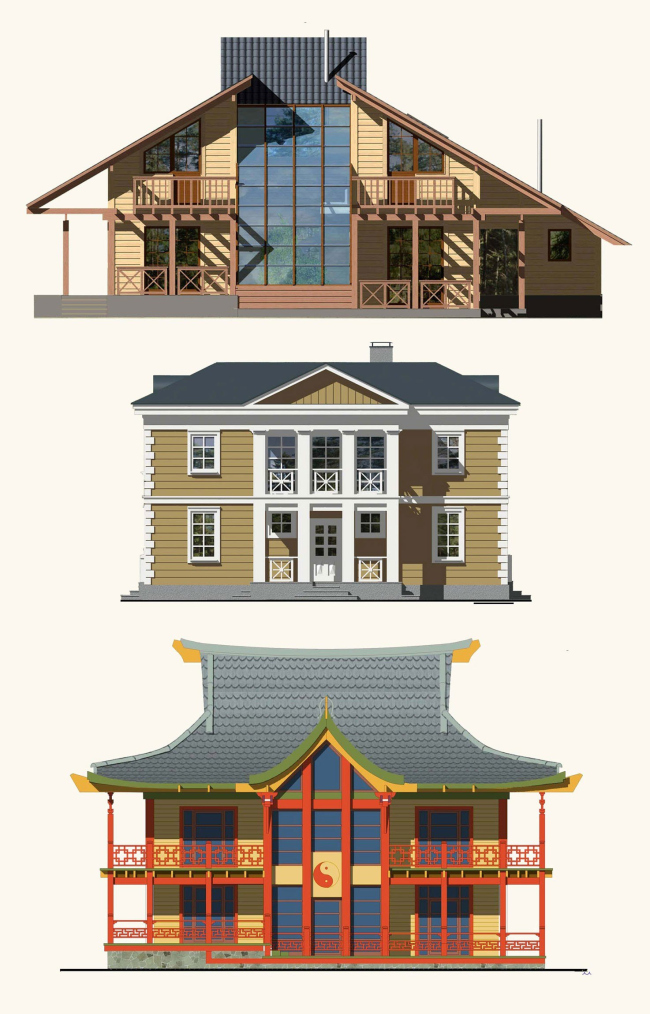

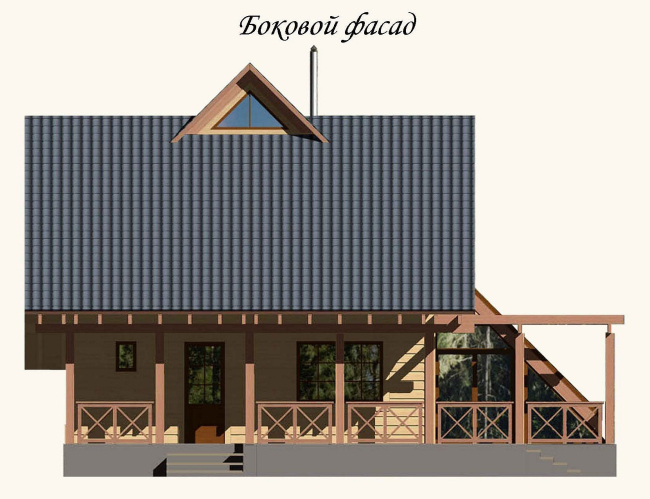

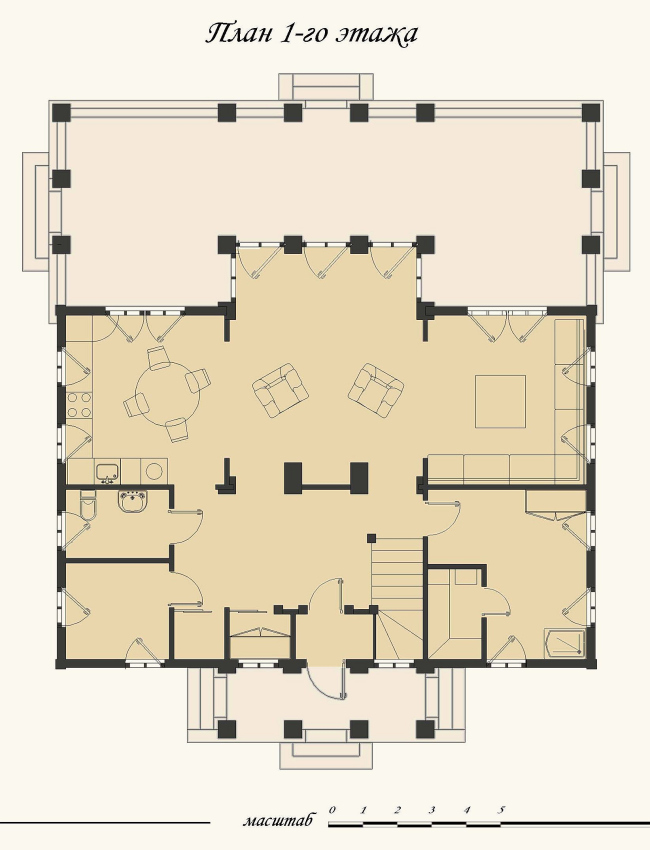

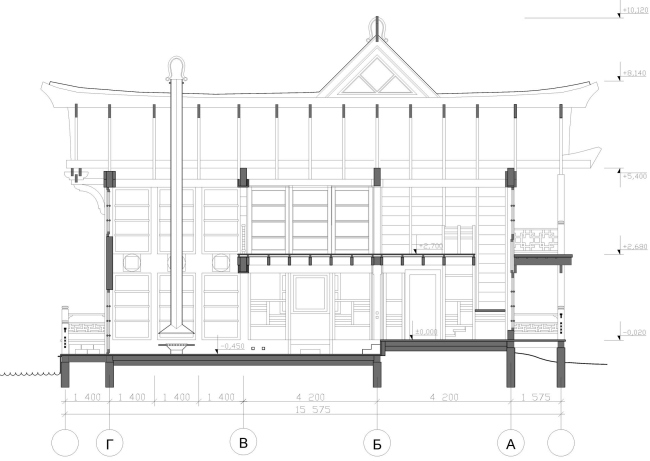

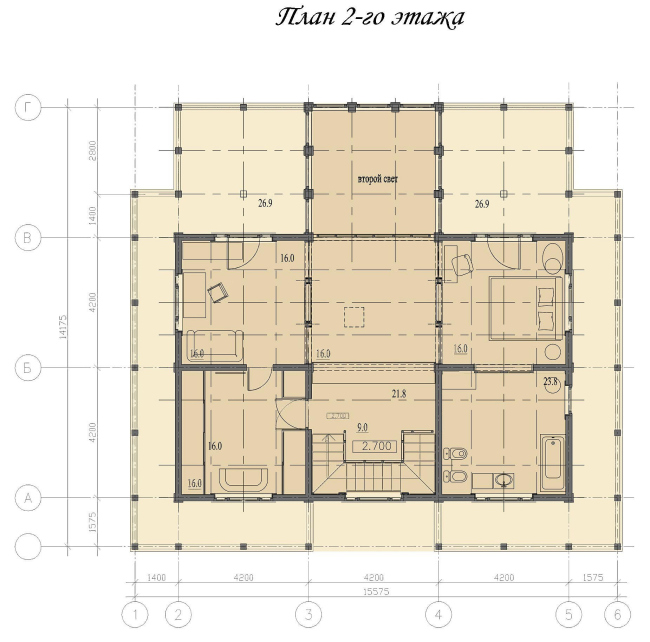

Oleg Carlson built three wooden houses in Moscow’s suburbs - all three having similar layouts based on one shared module. In spite of the similarity of the layouts and almost the same sizes, the houses look very unlike one another – one can even say that each of them represents once certain epoch in the history of architecture. Imagine a quadrant that is divided into 9 equal cells, the side of each cell being 5 meters. All the three layouts are drawn within this simple and unsophisticated framework; they only occasionally cross the outline of the main quadrant. Five of the squares, including the central one, form an equilateral cross that serves as the core of the composition of each house, making it center-oriented and grouping all the squares around the central one. This timeless classic had been strictly clerical until Palladio built his “Rotunda” villa, upon which it quickly made its way into secular residential architecture, adding a lot of grand nobility to it. And this makes it all the more exciting to examine the variety of solutions that Oleg Carlson was able to come up with. In the “modernist” Khlyupino house, the centripetency of the layout is not demonstrated to the outside observer. Rather, it is neutralized in a whole number of ways. First of all, one of the nine squares crosses the main outline - which makes the entire composition asymmetrical. Second of all, not all the three squares are even filled up – the two corner ones are “given up” to the terrace: thus the main, residential, volume of the house recedes back inside, away from the main façade surface. And finally, even though the cross clearly shows through on the layout, on the outside the stress is laid not on its upper central part but on the crossing of the two volumes. The second house of the three under study was built soon after the first one and not far away from it – the settlements of Khlyupino and Zakharovo are only some 10 kilometers apart. The settlement of Zakharovo is famous for the fact that the house of Maria Gannibal, Alexander Pushkin’s grandmother, is located here. Pushkin would be there from time to time back in his childhood, thanks to which some tourist routes go through the former estate. The house is not what it really used to be, though:it was completely rebuilt back in 1991. Still, Pushkin’s house – new or old – remains Zakharovo’s main tourist attraction. Thus, building the house for his commissioner in this settlement to the North-West from Gannibal estate, Oleg Carlson made use of the same layout but made the house look as if it was built in the classic style. Comparing this house with its Khlyupino predecessor, one can easily notice that a lot of things have been done here in a diametrically opposite manner. The main façade does not retreat and does not hide behind the terraces – here it looks like a wall with a clearly perceived center, outlined by the four-column portico with a triangular pediment. The terrace is also there but, as is the rule for the classical manor house, it commands the backyard and forms a park façade. The veranda is also there but here in is inbuilt into the opposite pediment whose arrangement of columns is also paned with glass in the “dacha” style. It is worth mentioning, for the sake of fairness, that this stylistic solution does not actually refer us back to Pushkin times. The house looks nothing like Gannibal’s abode with its thick round columns and drawn blinds, even though there are definitely some “architectural quotes” to be seen - for example, the windows the upper pediments of which border directly on the eaves. Looking at Oleg Carlson house, one can observe both “Pushkin” classics, and neo-classics, the style of dachas of the early XX century, and even some hints of Stalin era “health-houses”.Plus – some of the inevitable “Anglicism” of today, for example, the fireplace and the staircase in the drawing room. This house can hardly be pigeon-holed to one certain style, rather, this is a generalized image of a Russian manor house,not too large but very cozy. The third house was built still later on in the park of “Modern Estate”. This is the “Chinese” house for the owners’ daughter. Here the “center-oriented” layout is explored to capacity: the five squares on the layout fall into the equilateral cross; in the center of which there is this high-ceilinged double-height drawing room with a fireplace in its center. A great place to sit by the fire and under the roof at the same time (think back to Khlyupino house with a similar solution where one could sit on the terrace but under the glass roof)! Thus, the house is built around the fireplace – the solution that’s so classical it’s almost archetypical. One should say, however, that the living room is a little bit wider than the central square, i.e. the layout does not limit the volume in the strict sense. The fact of this house being “Chinese” is clearly seen from the first sight: bright-colored, surrounded with balconies with wooden openwork frames, with its massive roof that curls up at the edges, with its Chinese little bridges, a gate, and a gazebo (all three having authentic prototypes) – even from afar, the house can easily be described as a “Chinese” one. The “Chinese” stylization, however, is not done in this case in the literal sense:the author himself confesses that he opted not to replicate any particular Chinese êîíñîëè but settled for the ones that simply looked very similar. Rather, here we are dealing with the so-called “Chinoiserie” (the European imitation of the Chinese style. NoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNoneNone |

|