|

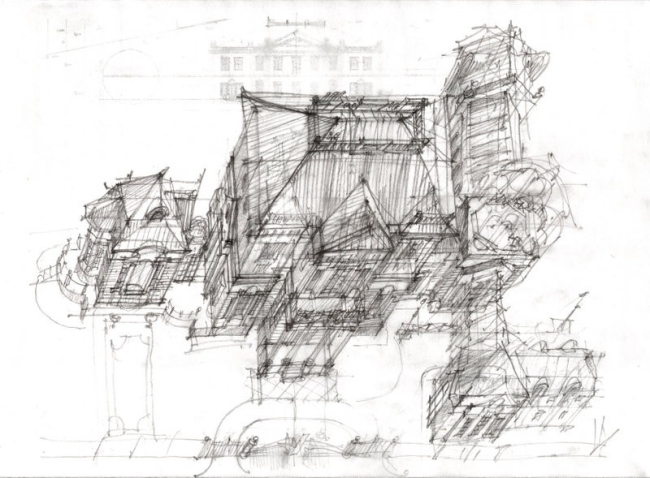

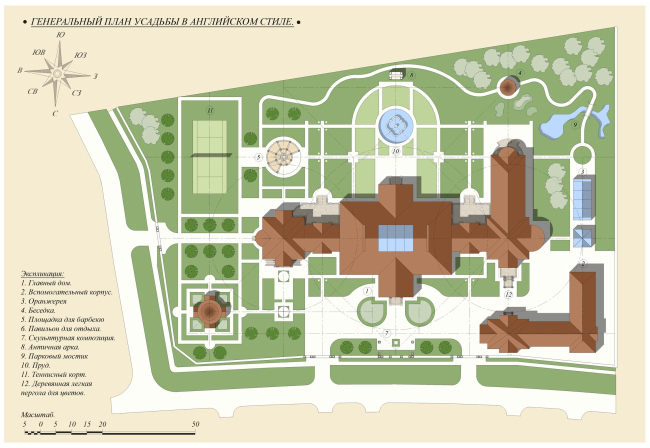

In this issue, we present the project of an “English House” – a palace built by Oleg Carlson for a commissioner from Moscow region. The facades of the house simulate the image of a British country palace and serve to conceal a complex and intriguingly sophisticated multi-layer space behind them.

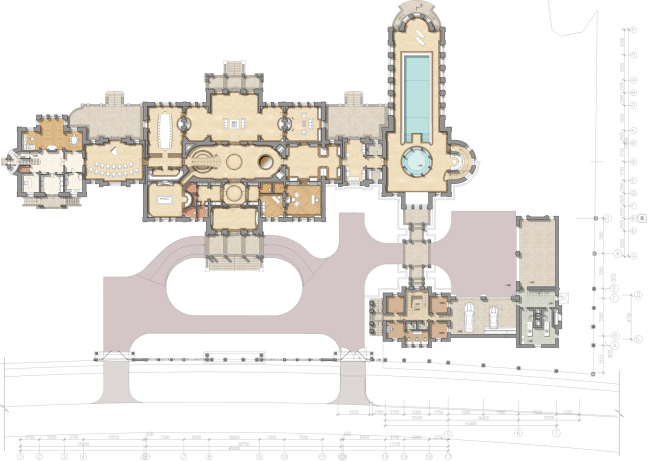

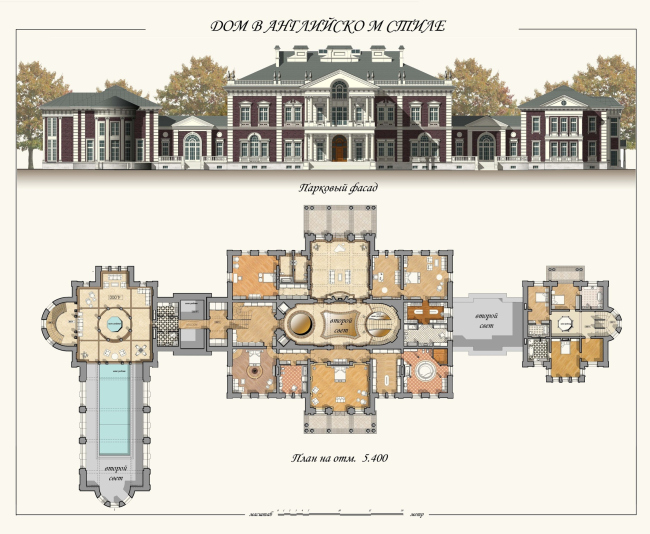

The central

part of the house is a large two-storied volume, crowned with a hipped

steep-pitched roof. The two main facades, turned onto the street and

onto the woodland respectively, sport a double-level balcony portico that

protrudes far ahead and thus becomes a very spacious one; in the summertime it

will become a cool shady terrace full of fresh air, and in the wintertime it

will also make a safe shelter from the snow. The side walls of the house are

branching with two wings that also serve as overpasses leading to two little

side houses, also double-storied but less tall and of a more stone-architecture

character: they have fewer walls and more windows, no porticos but instead they

get the semi-circular exedras, the shapes that are capable of giving the indoor

space and the outside facades the air of light elegance of the classicism style.

At the first glance cast at the main façade of the house with its wings and

overpasses, the architectural ensemble look perfectly symmetric. This is not

the case, however. One of the

two outhouses is stretched transversely to the main longitudinal axis, and for

a good reason: it contains the swimming pool, an essential attribute of any Moscow area palace of

today. In fact, this is a “water house”, or a spa, as people prefer to call it

nowadays, one that a person interested in the antiquity (which would make sense

in the classical environment) might have called a miniature version of the

Roman thermae. All the more so, because it’s not one but two pools that are

going to be placed here: the circular warm one, under the dome and surrounded

by eight columns (the real Roman caldarium), and an elongated cold water

swimming pool. Above the circular pool, just as at the end of the

elongated one, there are two large niches (these are the already-mentioned

exedras) that give the indoor space its classic grace and polish, turning it

from the trivial “spa” or “bathhouse” into the real thermae. The effect is enhanced

by the sculpture that will be placed in one of the niches.

There are several historical

“reminiscences” of this kind in the house, the most noteworthy one being the

underground rotunda in the basement floor. It is surrounded by an arched

colonnade, and the deck of the first floor above it is cut by a large circular

opening surrounded by a balustrade. Entering through the front porch, the guest finds this opening on the

right, and, leaning on the balustrade, he or she can take a peek into the

semi-underground world to see the arches, the columns and the statue – effect

similar to the discovery of the crypt in the cathedral or an ancient cellar,

excavated and preserved by archaeologists in some museum. This is a

theatrical technique, designed to make the front space of the palace

interesting and fascinating to the visitor.

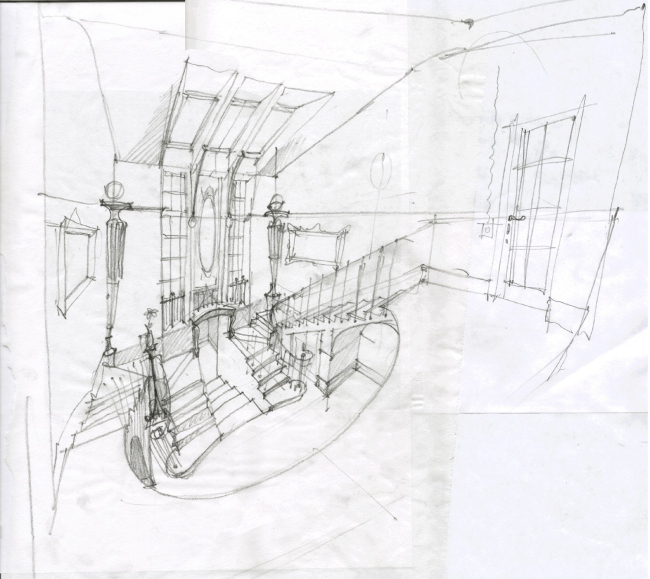

Higher up, directly above the opening of the “rotunda”, in the ceiling of the

first floor (or, if viewed from above, in the floor deck of the second), there

is yet another opening, just as round, with a balustrade. One can also look

down through it to see the underground columns in the perspective of two occuli

– this must be even more fascinating. Nearby, in the floor of the second

storey, directly in the middle of thee hall, there is yet another “well”… a

window that opens downwards. And finally, still higher up, in the ceiling of

the second floor, there is yet one more opening, this time large and elongated,

in the shaped of a smoothed-out “eight” – this topmost layer is turned into a

balcony skirting the main halls along their perimeter. The entire structure is

covered by a glass ceiling that turns the whole space into some kind of atrium,

or a glass-roofed courtyard.

Thus the four tiers of the front part of the house get interconnected with

multiple vertical ties. The entire space is literally “stitched though” with

air wells, and the whole intrigue is based exactly on that. The guests (as well

as the hosts) can not only wander up and down the house but also look up and

down the wells, seeing one another’s eyes. Coming to mind are things like baroque, mannerism, and, of course, the

oculus, painted by Andrea Mantegna in Camera degli Sposi. In the latter,

the ceiling bears the picture of a round opening with clouds beyond it and curious

faces looking in. In the Moscow

area palace this picture is not a painted one but it sure is implied and

conveyed by architectural means.

The main impression, however, is made by the staircase leading from the first

floor to the second. One central staircase leads down, and two sets of stairs

lead up. This is a real grand staircase, the kind that in some modern feature

film about the English aristocracy Cinderella beauties and queens would go down.

It is not by chance that the English are mentioned yet again: the house is

built in the English style. Over the past 10 years England gradually turned into a

standard of “good living”, so it is not surprising that the simulations of its

architecture are becoming more and more popular among Russian customers. Building

a good recognizable English house is actually a tall order, though. The thing

is that the English architecture, though recognizable, is extremely diverse. If

we are to take English Palladian Style, for example (the most chaste Palladian style

in the world, in which the British historians take so much pride), then we will

see that it is not very much different from late Russian Palladian style of the

XVIII century. Besides, as early as in the late XVIII century, we already had

anglophiles of our own – president of Moscow Institute of Architecture Dmitry

Olegovich Shvidkovsky wrote a whole book on the subject. In a nutshell, if we take

a Russian manor house with columns, chances are that we will find a very

similar one to it in England.

So, what part of it is responsible for the recognition and really makes a

difference?

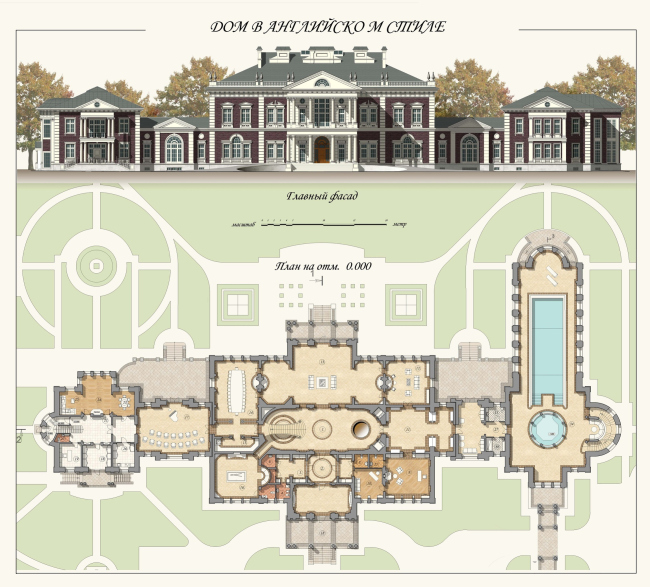

In this particular case, the architects base themselves on two things. The

first one is that same Palladian style: the portico, the two almost-symmetric

outhouses, the Palladian windows from the renaissance treatises (vertically

divided into three parts, the top section finishing in an arch). The second one

is the English renaissance of the Jacobean era, characteristic of which are the

red-brick walls with white rusticated stones on the corners, high-pitched roofs

(but with no garrets that were at the time so popular with the French), and

with large chimneys (in this case, the little decorative walls simulating these

chimneys crown the roof, masking the glass above the atrium). The large windows

with the perpendicular white stone sashes of the recognizable vertical

proportions dating back to the Tudor gothic style...

Or let us take a look at such a decorative device: two windows are “glued”

together to form a single one and get one common gable with a small acroter in

the shape of a classic obelisk. The twisted phials over the balustrade

surrounding the roof are not gothic and not quite classical either. For a long

time, England

reluctantly studied Renaissance architecture, taking it from a third source -

from the Flemish and the Germans. And then, as studiously as it had resented the

pure “classical” forms, it started studying the legacy of the High Renaissance

and the Antiquity. After which, with just the same zeal, it turned back to its

own past (it is common knowledge how protective the British are of their

traditions), and in the XIX it created the architecture following in the

footsteps of Jacob the 1st era, and that eventually got the name of

Jacobean. The XIX century simulations are not to be easily told from the

buildings of the XVII century, though.

The version of the English house proposed by Oleg Carlson is somewhere in the

middle between the Jacobean architecture of the early XVII century, Palladian

style of this same century’s second half, and the Jacobean architecture of the

XIX century. Probably, it is this oscillation between the pure classics and the

national peculiarities that the entire English architecture of the new era is

all about. It must be admitted that the architect made the grade and the house

looks recognizable indeed.

Recognizable, even though the main effect of this architectural project lies

not on the outside, of course, but on the inside – in the four-tier grand

atrium of a hall, in its multi-layer saturated space, “packed” inside the

respectable British walls, just like a surprise into a gift box might be. None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

None

|