|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 25.11.2025 | |

|

A Golden Sunbeam |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

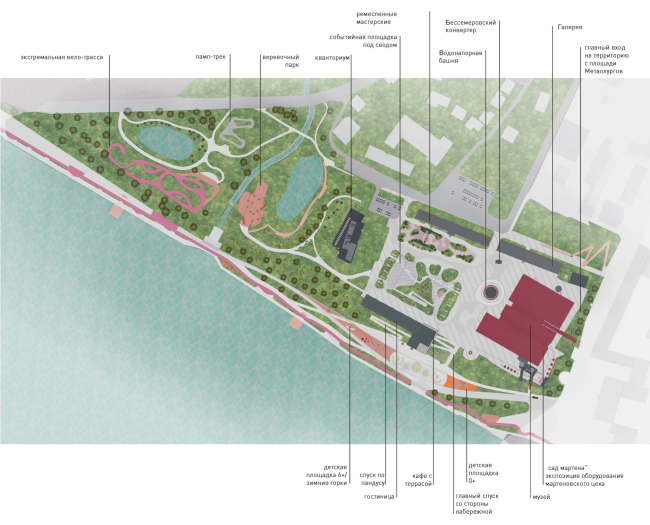

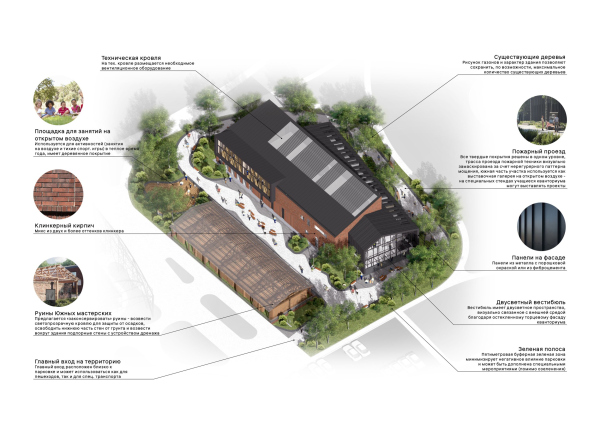

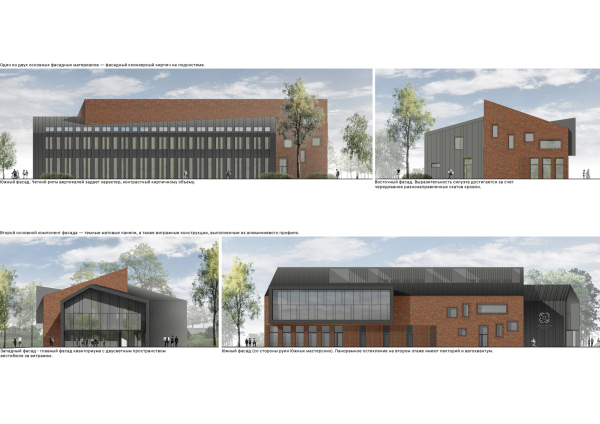

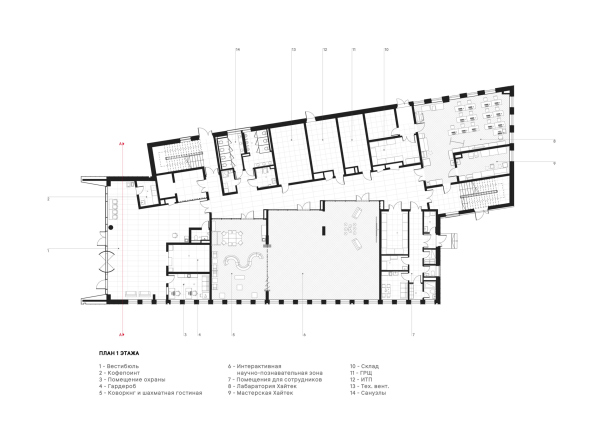

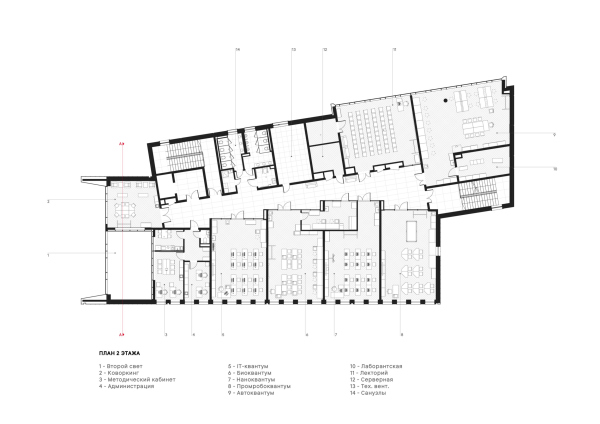

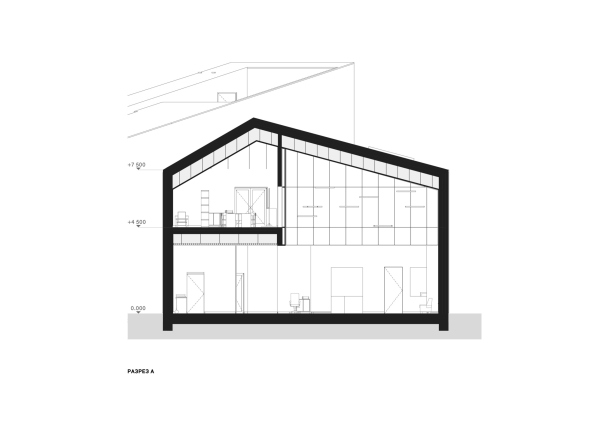

| Architect: | |

| Andrey Gnezdilov | |

| Studio: | |

| Ostozhenka Bureau | |

|

A compact brick-and-metal building in the growing Shukhov Park in Vyksa seems to absorb sunlight, transform it into yellow accents inside, and in the evening “give it back” as a warm golden glow streaming from its windows. It is, frankly, a very attractive building: both material and lightweight at the same time, with lightness inside and materiality outside. Its form is shaped by function – laconic, yet far from simple. Let’s take a closer look. “Quantum OMK” in Vyksa is the country’s first children’s technopark with a metallurgical focus. It opened recently, in October, alongside the relocated Shukhov water tower. Enrollment for the children’s groups began in September.  Andrey Gnezdilov, Ostozhenka Bureau We were offered a design code based on industrial materials: black steel and brick. So from the very start we put together two volumes – literally two pieces of foam on the model, two halves. And we added a diagonal. Why? Because the building is very small; without a diagonal, its interior would begin and end almost immediately. And even with the diagonal, it needed some kind of device, because the two halves sat next to each other unconvincingly, as if they were “slipping apart”. Once the jagged corridor was conceived, everything fell into place. I’m very pleased with how it was built; the impression on site turned out to be much better than I expected. What’s more, we never once traveled to Vyksa for site supervision – everything was done remotely. The stained-glass window came out well, exactly as we intended: the mullions are arranged not in a regular grid but in a free pattern. Initially we planned that with the reflection of the trees in mind. Now the trees are gone, but perhaps it’s just as well – the vegetation was kind of redundant in this instance, and instead the glass reflects the sunset, for which the asymmetrical grid is also more appropriate. Or take the ceiling of the coworking space and the exterior canopy – they align visually, and I know how difficult it is to achieve such precision from the builders. All in all, I think we managed to realize it with high quality. And in the evenings it glows yellow from within. Why? Because many interior spaces – starting with the staircases, and even one of the round columns in the entrance atrium – are painted yellow; the shade resembles “cadmium yellow medium”, though perhaps a touch softer. It amplifies the sunlit highlights, and at night it adds warmth to the light. Yellow is, of course, often used in schools and other children’s facilities, but usually in a straightforward, almost literal way. Here, for the first time so far, I think I’m seeing a different approach – one that is based more on reflected light. There’s plenty of yellow, yet it doesn’t dominate; instead, it “flares up”, alternating with white surfaces, black metal, glass, and various volumetric-spatial compositions. I would even say this: all the many “sunbeams” and “little suns” here have acquired a different, more spatial dimension here, which is why the somewhat overused but entirely fitting phrase “a sunny building” comes to mind – and stays with you. The architects have managed not only to bring in ample daylight but also to establish a dialogue with it, a peculiar kind of sunlight-based scenography. There is a plenty of light: the building is permeable, pierced by windows in the walls and roof, by glazing and glass classroom partitions that face the corridor. At times it even feels as though a stray sunbeam might sneak its way from the southern façade to the northern one. All this despite the fact that the building is not a “glass prism” when viewed from the outside. From the exterior, there isn’t actually that much glass – and no child-oriented cheerfulness either. Instead, in line with the design code and current tendencies, the materials are natural. The building is indeed composed of two volumes joined along their longitudinal sides and set at an exact 10-degree angle to each other. It’s hard to say where this angle came from; most likely the building’s footprint was defined by the land site, and overall it fits into the city grid, which in turn aligns with the pond constructed still in the late 18th century to serve the then-operating factory. Even so, the northern brick volume runs parallel to the factory’s brick ruin, though it differs in color – not red terracotta but dark brown. And in fact, the dialogue is not only with the ruin but also with the new Shukhov Hotel by Frontarchitecture, also a brick-and-metal structure, though built with red brick… The two volumes are like conjoined twins: one facing the pond, the other giving a slight nod toward the hotel. They are also joined like a three-dimensional puzzle – the kind architects of ASNOVA liked to draw and model in the 1920s, later reappearing in “plastic” form among children’s toys of the 1970s and 1980s. The façades of the two volumes differ strictly by material: one is brick, the other metal. Yet the black-metal portion “cuts through” the brick one, projecting northward as a TV-like cantilever. In reality, there is no internal volume passing through the building and extending outside: the cantilever contains a conference room and a large classroom with full-height glazing facing the Shukhov tower – the park’s main landmark. This effect is created entirely by the plastique of the volumes. The brick one has a single-pitch roof, forming trapezoids on the end walls. It is as if the building were a longitudinal half of a structure sliced along the ridge. The raised section hides the technical roof structures; there are no boxes or utility “huts” – which is the right choice, since the building is a low-rise one, and its roof is visible both from the dam and from the upper floors of the hotel. The metal volume has two pitches and, on the western side, the characteristic barn-house silhouette with glazing framed by a thick metal surround. But the volumes are arranged so that, especially from a pedestrian’s viewpoint, the metal one seems to extend a “hand”—or rather a large head—through the brick volume, peeking curiously at what lies on the other side. The top surface of this “head” is aligned with the ridge of the metal roof, which visually binds the two materials more tightly together. That is not the point, however. We have already grown accustomed to alternating brick, glass, and metal, and to five-sided gable contours. What matters here is how effortlessly they combine, forming a unified architectural image while offering varied perspectives, revealing lines of intersection, and in some views creating wing-like shapes reminiscent of interlocked fingers. Each material of course has its own characteristics: brick lends itself more naturally to a painterly scatter of differently sized windows, while metal favors the regular bands of standing-seam joints. Yet even in the brick section there is room for orderly verticals, balanced by equally regular hatching of horizontal relief bands. A look at the plans reveals that the northern brick volume with its single-pitch roof contains both of the staircases, the eastern and the western one – which is unsurprising, since the most asymmetrical windows belong to the stairwells and, hence, to the brick volume. The northern corridor wall is straight and runs parallel to the exterior wall. The “steps” appear on the southern side, where they run parallel to the outer façade. These steps are by no means arbitrary: essentially, classrooms of different lengths are arranged in a row. Because of the diagonal corridor, the northern volume “sinks into” or “dissolves within” the larger footprint of the southern rectangle. The northern part houses, on the second floor, the conference room and the large “Autoquantum” classroom, and on the first floor an equally spacious “Metalquantum” classroom; notably, this one is marked on the façades by the horizontal brick striping. Meanwhile, the southern part contains all the specialized classrooms on the second floor – IT Quantum, Bioquantum, Nanoquantum, and Promroboquantum – and, on the first floor, two open social spaces: the interactive science-and-learning zone and a coworking area with a chess lounge. This is a logical arrangement, as the southern façade receives the best daylight. The stepped projections of the classrooms give the corridor a discrete, perspectival quality: it widens and narrows in turn. What emerges is a corridor that is not “corridor-like” at all in the conventional sense. Viewed from different ends, it feels entirely different – when seen from the east, it is a smooth, wide funnel. Yet it recedes energetically, “quickly”, into the depth; a black ceiling grid marks the boundary of the northern volume, while a slightly higher yellow “southern” grid of transverse lines emphasizes and develops the theme of collision, the “angle of encounter”, revealing the building’s plastic nature in its interior. It makes the space decidedly not boring – not decorated for decoration’s sake, but fully considered. Viewed from the west, from the main entrance, the yellow wall segments face the visitor: they arrest the gaze, and very successfully – they carry the classroom names. And I should emphasize: all interior decisions, including those yellow columns, were also designed by the Ostozhenka architects. If only it were always done this way. The best-lit parts are the end walls. This also applies to the northeast corner: here a stained-glass wall helps – northern, yes, but stretching across the entire facade. But primarily we’re talking about the entrance atrium. Its western wall is fully glazed and beautifully reflects the sky at sunset. The southern windows bring in additional light in the afternoon – and since most extra classes take place at that time, it will be especially comfortable here. The atrium is double-height, but on the northern side, where the corridor meets it, a second tier of the coworking area is enclosed. It’s a very pleasant space. In the evenings – which, as we know, is the most active time for the Quantorium – it will be illuminated from, quite literally, four sides: the glass door from the corridor, the glass wall facing the atrium, the western fragment of the entrance glazing. And the northern wall, white and with a broad slope, reflects and gathers daylight. All in all, it’s remarkable how much architectural positivity – working directly to create the right atmosphere – emerges in this rather small, simple, and restrained building for children. Add the new equipment – which is easily visible through the corridor’s glass walls – and you get a spark of positivity perhaps even more significant than the preserved Shukhov water tower (though that, too, is important). We don’t know who, how, and under what programs will be teaching the future young metallurgists, hoping to keep them in their hometown and spark interest in the profession. But judging by the atmosphere embedded in the Quantorium building and perceived on an emotional level, the foundation has been laid.  Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ruQuantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Sergey yasinskiy / provided by OMK Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in Vyksa, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Xenia Kokorina Quantorium in Vyksa, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Xenia Kokorina Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru“Shukhov Park”. The masterplanCopyright: © ÎÌÊ / Vyksa “Shukhov Park” and “Quantorium”, birds-eye viewCopyright: Photograph © Andrey Efimov / provided by OMK press service “Shukhov Park” and “Quantorium”, birds-eye viewCopyright: Photograph © Andrey Efimov / provided by OMK press service “Shukhov Park” and “Quantorium”, birds-eye viewCopyright: Photograph © Andrey Efimov / provided by OMK press service “Shukhov Park” and “Quantorium”, birds-eye viewCopyright: Photograph © Andrey Efimov / provided by OMK press service Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Plan of the 1st floor. Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Plan of the 2nd floor. Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in Vyksa, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Xenia Kokorina Quantorium in Vyksa, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Xenia KokorinaQuantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The corridor. View from the east. Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru The corridor. View from the west. Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: Photograph © Julia Tarabarina, Archi.ru Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects Quantorium in VyksaCopyright: © Ostozhenka Architects |

|