|

Aleksei Ilyin has been working on major urban projects for more than 30 years. He has all the necessary skills for high-rise construction in Moscow – yet he believes it’s essential to maintain variety in the typologies and scales represented in his portfolio. He is passionate about drawing – but only from life, and also in the process of working on a project. We talk about the structure and optimal size of an office, about his past and current projects, large and small tasks, and about creative priorities.

Archi.ru:

Your architectural office was founded – if I’m not mistaken – relatively recently, around 2020, correct? And yet it’s already well known for competition entries and major projects. What are you working on right now? Do you specialize primarily in high-rise construction in Moscow?

Aleksei Ilyin:

We prefer not to limit ourselves to any kind of specialization – on the contrary, we take on fundamentally different tasks, projects of various scales and functions. I myself, for example, was deeply interested in working on my own house, which has been included in the recently published TATLIN book “The Architect’s House”.

That said, yes – we do follow current trends of the Moscow architectural market, and right now we are working on several high-rise projects. A few large complexes are currently under construction: the Voice Towers residential development, Nagatino iLand. At Amber City, eight floors of the first phase have already been poured in concrete.

For one of the blocks in the Shagal residential complex, we proposed quite diverse façades responding to the proximity of the water. All this is now in the implementation phase. The office for Rail.a in Perevedenovsky Lane is almost complete. We also have five large projects that we are not yet allowed to reveal.

What is the tallest height mark among your current projects?

At the moment – 360 meters.

I remember you took part in Moscow’s “Renovation Façades” competition and won in one of the categories. Later, the same sculptural idea – towers with a rounded, cylindrical top – appeared in your Voice project. I’ve been wanting to ask: what’s actually located in that upper part?

Under this “vault” there is a spacious double-height volume that accommodates both a penthouse apartment with a terrace and a technical floor. In that project, we didn’t have the opportunity to experiment with a varied-height composition – height restrictions were still in force. That’s why the buildings are all the same height, but they differ in color and are placed at a right angle to each other; this allows the semi-cylindrical tops to “animate” more actively. In addition, each tower gains distinctive end façades.

What fundamentals guide you when working with high-density complexes of this kind today, when designing for Moscow?

The set of these principles is fairly well known. Naturally, we aim for multifunctional public spaces at the pedestrian level, as well as for creating comfortable environments both outside and inside. This includes modern architecture that is diverse – when viewed up close and from a distance – in form, texture, and silhouette. Today, density can be distributed vertically: we can vary building heights from mid-rise to maximum, working with volumes at different levels to form something like “layers” of urban perception – near, middle, and distant. This gives us considerable freedom of maneuver.

When you speak of modern architecture, what do you mean? Glass and metal?

Glass and metal – among other things; you can’t avoid them in large-scale contemporary construction. But not only, and not primarily. Today, every architect finds their own solutions within a broad spectrum of the contemporary “alphabet”. I like modern materials, fluid lines, work with volume, color, and large, dynamic forms – but I also consider details, modeling, and small nuances to be equally important, especially those details that are usually perceived at the pedestrian level.

For example, on the tiny plot surrounding the Rail.a office building, we proposed embedding “rails” into the paving – both metal ones and “light rails”, illuminated strips. Both of them respond to the proximity of the actual railway.

Tell us about this project. Is it almost finished?

Yes, construction is already at an advanced stage; the building is half clad, and I think it should be completed this year. We’re currently watching the finishing process closely.

On three sides, there is a standing-seam façade with a streamlined, shell-like form – like a hull or a seashell, in the spirit of streamline or aerostream design. And the fourth façade, the one facing the railway tracks, is designed as a kind of showcase turned toward the passing trains. I must say, it’s quite a striking sight; I myself wouldn’t mind working in such an office. Rail.a designs bridges and roads, so the transportation theme is relevant to them.

Listening to you, I get the sense that you take the quality of project execution very seriously. Do you always manage to retain on-site supervision?

So far, yes – and it’s an important stage. It’s also very inexpensive; site supervision isn’t economically justified, of course, but for us it is extremely important.

What stages of project documentation does your office handle? Concept, P, working documentation?

We always work on Stage P – the project stage – it’s essential; without it nothing will work. For the working documentation stage, we invite trusted colleagues.

We have long-term partners, “Project 2018”. The company was founded not by an architect, so we have no creative friction or overlap. They have chief engineers, structural specialists, a large team of designers, and we have a good working rapport with them – together we can quickly find the right solution. It’s convenient for both sides in many respects. All our major projects are done jointly.

If we were to take on the working documentation ourselves, the company would automatically have to grow to a hundred people – and I wouldn’t want that.

How many employees do you have now?

Thirty to thirty-five. Our turnover is very low, and the team is young. We have students working for us as well. One girl just went to Milan to take her exams… We have a chief architect of the studio, Igor Simoroz, who oversees all projects. And we have several lead architects too.

You mentioned diversity. What other projects contribute to it?

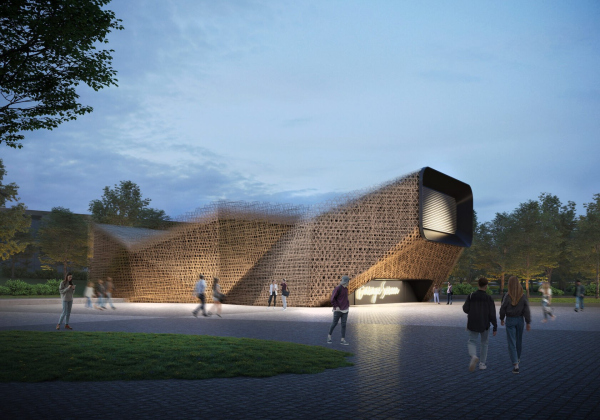

Here’s a complex project – the Space Conquerors Park in the Saratov Region, which we designed together with the company “Krasny Kvadrat”. It is supposed to be built, but it’s a public contract, which means the process is complicated and slow. It’s a gigantic entertainment complex with numerous pavilions. We tried to avoid the garish “Disneyland” aesthetic and instead create striking, interesting things – for example, we used printing on metal.

Or take the project that we did for Mineralnye Vody. It never went into development, but it did win a Silver Sign at last year’s Zodchestvo festival. We even made a special wooden model for the exhibition – so the recognition was unexpected and pleasant.

What makes this project different? The curved form?

Not only that. The buildings weave around the valuable trees on the site, and that’s what defines the shape. The ground level is entirely public – you could walk through everywhere and reach a viewing platform, and the panorama there is spectacular: the platform is on a slope, high above the ground. The core of the complex was a multifunctional concert hall. There isn’t such a hall in Kislovodsk yet, so when celebrities come, there’s nowhere for them to perform.

In addition, we proposed running pipes with mineral water into the complex – you know, specialists say that bottled mineral water has barely more benefit than plain water. So we included a “mineral-water conduit”. Unfortunately, the project isn’t progressing at the moment.

Do you take part in competitions?

That’s a complicated topic. In general, I really like competitions. Back in our student years, Alexander Tsimailo and I admired Brodsky and Utkin and their etchings; we practiced hatching with a rapidograph ourselves and sent our drawings to Japanese competitions – though we didn’t win there. But we did win in Chicago and even got a monetary prize of $7,000. We immediately spent it on a trip to Europe, and saw a lot at the time: Barcelona, Paris, different places. Later on, we worked on our diploma project together – ten boards with dense hatching; Nikolay Lyashenko helped us back then. He had just returned from Germany, and together we made a model, the likes of which simply did not exist at that time, in 1996 – with trees, with people, little wires…

However, not all competitions make you happy. For example, we took part in a closed-door competition for the riverfront quarter in Tushino, from Asterus. We designed buildings of different formats – from townhouses to towers, stepped forms, terraces, large through-openings, and for “dessert”, a round building called the Colosseum. We worked very hard. But we didn’t even make it to the final. We later tried to find out why – they told us it came out too complicated.

Or take the recent competition for the Fili transport hub. After speaking with the clients, we came away confident that they wanted a bold building directly above the road. So that’s what we designed – a frame-like structure, and if you drove along Bagration Avenue, from a certain angle Moscow City would appear framed inside it.

Together with our structural-engineer partners, we calculated how realistic the proposal was, including the possibility of building over the roadway without closing it for a long period: it would be possible to stop traffic for two hours, bring in the truss, and lift it with a crane. We also came up with a “snail” – a ramp descending from the overpass. It was an interesting project, two centimeters thick in documentation. And most importantly – completely feasible. We didn’t win; it’s possible the boldness of the proposal played a role. We also took part in the Garage Screen competition in 2022.

Still, as an author who has taken part in many competitions – could you share some life hacks?

I think there are three. The first one, and I understood this quite a while ago: if a beautiful idea comes to mind immediately, you need to forget it. Ninety percent of participants will think of the same thing. The second: the presentation has to be great. The jury looks through hundreds of projects, as you know yourself – that’s a lot. The presentation has to catch their attention first and foremost. The third rule is a strong idea. Of course you need one. But it comes third because if you have a good idea but can’t present it properly, it’s all pointless.

Do you teach?

Not anymore. I taught for a year and a half at MARCH – it gave me tremendous experience, but it was also a huge workload. I took the task very seriously… Even though we had only twelve people in the group, I think. Two of them worked at the office afterwards; then one moved to St. Petersburg, the other to Switzerland.

Teaching is a good thing. When you start explaining something that seems completely obvious to you, you end up articulating it clearly. That’s the main benefit. But teaching demands a lot of effort, engagement, and participation in all processes. Maybe I’ll return to it a bit later.

You’re known as an architect who draws. What do you draw, and how?

I always draw only from life. Drawing from a photograph doesn’t interest me.

So, like the Impressionists, of whom Degas said they were ready to perch over a cliff and paint, paying no attention to anything?

Well, I’m more like Marquet, you know – there’s that painting where he’s sitting on the beach in a suit, bow tie, hat, painting while it’s hot and children are running around. Although I don’t like it when there are a lot of people around – that gets in the way.

And your subjects? Do you draw architecture?

Not necessarily architecture – anything that can be drawn. Although I’d put it this way: I’m more interested in cities than, say, natural landscapes. But I can’t manage it in Moscow – in Moscow it’s all work, so I mostly draw while traveling. I went to visit my daughter in Amsterdam, she’s studying there – and painted a bit too. Now she’s going to London on an exchange – I’ll go as well. My older daughter is already a professional artist, she loves working in oils and has had several exhibitions. Now I’m teaching my younger daughter, she’s six.

Your technique is a black outline combined with watercolor?

I generally like mixed media. For the outlines I use a Chinese brush – it’s similar to a felt pen; there’s a small reservoir inside that you fill with ink. It can produce very fine or very thick lines. Then I use watercolor, and refine things on top with a soft colored pencil; I usually have several. I love grisaille.

Have you had exhibitions as an artist?

A few. I took part in Archigraphics, and once even won first prize there. Then there was an exhibition at my friend’s gallery at Red October – I showed a series of lighthouses. At some point I got fascinated by lighthouses; and I should say, getting to a lighthouse – and the most interesting ones are mostly in Denmark and Norway – is quite a logistical challenge. In Iceland it was almost impossible to paint, although I managed to do something there too.

Your enlarged watercolors are placed on the end walls of the Filatov Lug residential complex. Do you often draw for buildings?

Never on purpose. In the case of Filatov Lug, something had to be done with that building – as you can see, it’s quite simple in shape. We decided to make murals. Using someone else’s works would have been complicated because of copyright issues, so we chose from my own. There are fragments of views of Amsterdam and Copenhagen; I should say Copenhagen is my absolute favorite city… Everything was drawn in AutoCAD. We found a way to print on porcelain tile – and I must say, the color reproduction came out fantastically well, I didn’t expect it to turn out that good.

Actually, I’m not sure things like that should be done on buildings, but that’s how it turned out…

Why aren’t you sure? There’s a long tradition of murals and monumental art – at least in modernism…

Yes, but first of all, it needs to be done intentionally. And here the situation simply called for enlivening the end walls of the buildings; I was surprised myself that it turned out pretty well.

Have you had any other similar experiences?

There was one interesting story, although it never materialized. We took part in the competition for the Ostrov Mechty metro station. First place went to TOTEMENT/PAPER, we came second. But then something went wrong, they called us in, and then they rejected our proposal too – because of the black color. The final version was done by Mosinzhproekt.

But that’s not what I mean. While working on the project, we studied the site, went to Ostrov Mechty. Many people have a justified skepticism toward the building, but as an amusement park it’s considered the best in Moscow. And there are these corridors, malls leading to the main hall – and they’re decorated as recognizable cities: Moscow, Paris… So in our project we created a reminiscence of that: we placed my drawings of Amsterdam and Antwerp on the station, creating a kind of “watercolor city”.

Yes, that was another experience.

But all of these are isolated cases – the result of circumstances. I don’t create sketches specifically for my buildings, nor do I aim to. In the design process, yes, I draw a lot. I draw projects down to the details; drawing is a way of thinking for me.

What about drawing for architectural presentation?

You know, a hand-drawn presentation today is a luxury. It takes effort and time. Just like a physical model. Everything has been replaced by videos and renderings. The client wants to see a photorealistic render. Sometimes, if we urgently need to produce a variant, I can sketch something based on a template – but that happens rarely; I can’t even remember the last time I did it.

How did you get started? I see several very well-known buildings in your portfolio. What did working in large firms teach you?

It taught me a lot, of course.

I started working around 1993, during my third year at the institute. Most architectural firms at that time focused mainly on private interiors and houses. There were only three private companies that actively participated in urban development: SKiP, “Reserve Union”, and “Group ABV” – the company of Pavel Andreev, Nikita Biryukov, and Alexey Vorontsov. They became, without exaggeration, my “fathers” in the architecture profession: teaching me, explaining how things work. Nikita Biryukov always supported and valued me. We spent all our time in the studio, drawing by hand, without computers – but it was precisely working at ABV that allowed me to immediately engage in urban design.

One of my early successes was working in the early 2000s on the Dukat office building, which was being built as a Heinz office by Americans for Americans – they were very active here at the time. The design-development stage was done by SOM. We worked on adaptation and even went to the U.S., together with the structural engineers. Back then, modern offices in Moscow were almost nonexistent, and we learned a lot.

Our generation, raised in the USSR, was highly motivated: faster, higher, stronger… Everyone strived for success. It was a kind of boom. Now things are somewhat calmer, I suppose. But constant progress and striving for new achievements seemed completely natural back then.

Later, I happened to have a German partner – Sergei Tchoban – and we opened the company called “Ilyin Tchoban”. Together with Sergei Kuznetsov, we designed the La Saluta sports and recreation complex in Taganka – which, by the way, was the first building in Moscow with curved volumetric ceramic façades.

Then you collaborated with SPEECH and started leading Studio No. 1?

Exactly. In part, I even helped set up the studio system there. My studio functioned as a separate unit; I collaborated with the company as a project partner.

You’ve worked on “Lotos”, “Novatek-2”, and the Kollektsiya Museum at ZILArt. Which of these projects is your favorite?

The Kollektsiya Museum, in my opinion, turned out well in implementation. Although, that’s no longer really my merit – it was my colleagues who worked on the construction documentation and brought the project to fruition. As for Novatek-2, I must say I was lucky: I was the first the client listened to, the first to present options. The one chosen was, in my view, the most interesting.

I value both the experience of realized projects and the professional collaboration with Sergei Tchoban.

Why did you decide to start your own firm? And when did that happen?

Why? I think it’s because I turned that page for myself. I needed to move forward. It happened during the pandemic, around 2020. A strange time: everyone was staying home, my family was out of town, and in the evenings I read A Hero of Our Time to them. At the same time, the pandemic period turned out to be turbulent. A lot happened during that time. But even before that, I already had independent projects.

Such as?

For example, the 2018 project – the Aalto House. It was built by the Finnish company YIT, and they brought quality materials from Finland, good-thickness metal without warping.

Let’s go back to the very beginning of your career. You have two “aspects” – artist and architect. How did it all start? Family? Art school?

My family isn’t architectural; my parents are engineers. I was “shoved” into art school. I can’t say I liked it at first, or that I was particularly good initially. I gradually got into it. But the key was my teacher, Vitaly Vsevolodovich Vernikovsky – a fairly well-known artist. He had his own style, painting with wood shavings – and he was trained as an architect. His students taught preparatory classes for entering MARHI (Moscow Architectural Institute) right there at the school. I observed and decided it was a good specialty: it gives a certain creative vision while still retaining a connection to reality, a healthy “grounded” quality. I realized early on that I wanted to combine these things, but I also knew I wanted to be an architect, not just a designer.

How do you distinguish between the two?

I’d say designers look at things fairly utilitarian. I, on the other hand, approach everything with interest. I’m always curious to come up with something new – whether it’s a small façade detail or a huge urban complex.

So, from the eighth grade, I started preparing, went to courses, and enrolled myself. I had no connections, no favors. I passed – at the passing score, I think 8 or 9 for head and composition, but in drawing, although I liked it and could draw, I made two projection errors – got a 4. Barely passed, in other words. Then I saw that half of my classmates couldn’t really draw at all… So, I realized I was incredibly lucky to have even gotten in.

Did you ever regret your choice?

Not at all. It just so happened that I never really planned to be anything else. So far, my work brings me nothing but joy.

A private residenceCopyright: Photograph: provided by Aleksey Ilin

Amber City housing complexCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsAmber City housing complexCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsVoice Towers housing complexCopyright: © Highlight Architecture & Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsVoice Towers housing complexCopyright: © Highlight Architecture & Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsRail.A. Office Center on Perevedenovsky Lane

Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsRail.A. Office Center on Perevedenovsky Lane

Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsGagarin Space Conquerors Park. *Vostok-1* Pavilion. Daytime view.Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsGagarin Space Conquerors Park. *Vostok-1* Pavilion. Daytime view.

Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsHotel complex with serviced apartments, a concert hall, and a spa, project, 2022Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsHotel complex with serviced apartments, a concert hall, and a spa, project, 2022

Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsCompetition for the coastal quarters of the ALIA districtCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsCompetition for the coastal quarters of the ALIA districtCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsMultifunctional complex of the Fili Transport Hub, competition proposalCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsMultifunctional complex of the Fili Transport Hub, competition proposalCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsGarage Screen 2022 competition proposalCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsGarage Screen 2022 competition projectCopyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsGrand-Place, Brussels. Paper, watercolor, black charcoal, pastel, Chinese brush. 2019Copyright: © Aleksey IlinLighthouse on Hiiumaa Island. Estonia, 2016.

Copyright: © Aleksey IlinFilatov Lug housing complexCopyright: Photograph: provided by SPEECHFilatov Lug housing complexCopyright: Photograph: provided by SPEECHCompetition design concept for the Ostrov Mechty metro station.

Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsCompetition design concept for the Ostrov Mechty metro station.

Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsDukat business centerCopyright: © Aleksey IlinDukat busineess centerCopyright: Photograph © Aleksey IlinSports and training center on Solzhenitsyn StreetCopyright: © SPEECHSports and training center on Solzhenitsyn StreetCopyright: © SPEECHNew headquarters building of Novatek, SPEECHCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Chebanenko /provided by SPEECHMuseum “Collection” at ZILArt, SPEECHCopyright: Photograph © Aleksey Ilin / Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsAalto housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Chebanenko /provided by Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsAalto housing complexCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Chebanenko / provided by Aleksey Ilin ArchitectsAmsterdam, 2016, Watercolor, 60×45Copyright: © Aleksey Ilin

|