|

In this issue, we speak with Dmitry and Oleg Shurygin, founders of the company MV-PROJECT, which has extensive experience in designing theater and entertainment buildings as well as working with cultural heritage sites.

MB-PROJECT is one of the country’s leading developers of theater-type projects and restorations of cultural heritage sites. Their portfolio includes dozens of completed projects and many professional awards. Today, the founders of the company are actively involved in the development of industry regulatory documents: their accumulated experience and qualifications make their expert opinions valuable for the entire professional community.

We spoke with MB-PROJECT partners Dmitry and Oleg Shurygin – who, despite having the same last name, are not related – about the history of the company, its specialization, and the advantages and challenges of working with commercial and public clients. This coincidence of the founders’ surnames has more than once led to awkward situations, but it has never prevented the partners from maintaining a friendly relationship and running a joint business, complementing each other harmoniously.

Archi.ru:

How did you guys meet?

Dmitry Shurygin: We studied together at the Architecture Department of the State University of Land Use Planning. Because we had the same last name, we were constantly getting into various situations together, which brought us closer. However, we studied well and both graduated with honors.

Oleg Shurygin: Studying came easily, and with every year my interest in architecture only grew. For me – I came to Moscow from Kolomna and lived in the university dormitory – the university life was especially fascinating. Over those six years a firm feeling formed that we had chosen the right profession.

But the idea to create a joint company came later?

D.Sh.: Yes, much later. While still students, Oleg and I started working in different organizations. In 2002 I joined the Central Research and Design Institute for Residential and Public Buildings, and started working in the studio of Valentin Stepanov, Russia’s leading designer of school buildings. Under his guidance I took part in several projects and even got involved in work on new regulatory documents for the design of educational institutions (MGSN 4.06-03 of 2004 and its guidelines). It turned out at that point that systematization was also interesting to me. Later this experience with regulatory work proved very useful when working on theater projects.

O.Sh.: I was one of the first in our student group to start working. In my second year at the State University of Land Use Planning, I was hired by Bergen Nachtigall, the office of Konstantin Vernigor, which at the time was among the leading firms in private architecture. It was a true school of design, project development and construction for me, a school of teamwork and client relations. Two years later, I was already heading a division with my own area of responsibility and projects. By the time I graduated, I had founded my own company, but after working another two years I realized the world of interior and private design felt too narrow, and I wanted larger-scale tasks and projects.

D.Sh.: At first I worked on the round Odintsovo school project at Central Research and Design Institute for Residential and Public Buildings. Then I gradually began to join other projects – schools, preschools, and higher-education facilities. One day I was invited to join the major-renovation project for the Gogol Theater, which happened to be right across the street from my university. I examined the building from top to bottom, immersed myself in theater technology, watched all the productions, and even analyzed the layout of the premises for compliance with current regulations. The document I prepared was used in the project and later became the basis for the technical brief for the theater’s reconstruction. Unfortunately, that project was never implemented, but the client liked the result, and in 2007 I was offered the development of projects for another nine theaters. I realized this was something that truly interested me and invited Oleg to join this large-scale effort. After just a few meetings with the client, we decided it was time to start our own company. We registered the legal entity in September, and that same winter began work – first on three, and then on another six theater projects – in our own studio with a team of ten.

O.Sh.: These were not projects for new buildings but rather for upgrading existing theaters. Formally, they were classified as major renovations, but in reality it was reconstruction within the existing structural shell. In the mid-2000s the distinctions between types of work were not strictly codified, so we ourselves had to find the balance between preservation and change.

At first, theater management viewed us with a fair amount of wariness – we were still young architects without an impressive portfolio of completed projects. We overcame the skepticism through our work: we improved layouts to make them more convenient for staff and audiences, and proposed striking design solutions. It was an intense and productive period – we had to very quickly master the theater sector and the specifics of working with public clients.

Speaking of public clients – at that time many offices were being created with a focus on private or commercial clients, whereas you immediately started working with public-sector projects. How difficult was it to build your practice in this field?

O.Sh.: Tender procedures developed in parallel with the growth of our company, so we had the opportunity to understand all of the subtleties. With each completed contract, we increased our own professional standing and could assess our work more confidently. Gradually, we figured out how the tender system actually worked, how to prepare the documentation, and we gradually began to act as the general designer on major state contracts.

D.Sh.: Now, thanks to our experience with government contracts, our bid has a significant advantage over competitors. However, every type of client has its pros and cons. The plus of public contracts is stable funding; the minus is the absence of advance payments and the fact that payment is made only after the work is fully completed. Because of the issue of unstable cash flow, we decided not to limit ourselves to public contracts and increased the share of commercial projects in our portfolio. We now successfully work with such high-profile developers as Sminex, A101, MR Group, and others.

O.Sh.: The drawback of developer projects is the long process of formalizing contracts, which often runs in parallel with the work already underway. The advantage is a flexible system of milestone payments throughout the year. A mixed portfolio of contracts allows the company to manage both financial and professional tasks much more smoothly.

So you didn’t limit yourselves to a single building type or a single type of client?

D.Sh.: We started with theater projects, but soon began designing schools as well – I know that typology very well. We also worked on other projects: exhibition halls, museums, and libraries.

From 2010 onward, we began working with cultural heritage properties. For us, this was a natural development, since many theater buildings hold protected heritage status.

O.Sh.: It so happened that while we were working on the major renovation project for the theater on Malaya Bronnaya, the building was granted protected heritage status. We had to make a lot of adjustments on the fly – we obtained a license from the Ministry of Culture and then reworked the entire project documentation to meet the requirements of the Moscow Department of Cultural Heritage. It wasn’t easy, but we handled it, and after that we began working systematically with architectural heritage sites.

D.Sh.: Since then, we’ve completed dozens of projects for listed buildings. We’ve learned to find the most delicate and flexible solutions that make it possible to restore heritage assets while giving them new life.

O.Sh.: Our task is to find the fine line between meticulous restoration, reconstruction, and adaptation – with the integration of modern engineering and safety systems. That line is very thin, but it is always there. You need experience, a trained eye, and enormous respect for heritage to find – sometimes – the only possible correct solution.

D.Sh.: A building must live and function, it’s a living being. Otherwise, even after the most careful restoration, it will deteriorate and fall into decay. That’s why in every restoration project we solve two key problems: the restoration itself, and the adaptation of the building for contemporary use. In most cases, the second task is the more difficult one. Sometimes it looks almost impossible. For example, how do you organize evacuation routes, or make a building accessible for people with limited mobility, or run ventilation through historic structures? And if you add theater technology on top of that, you can understand just how complex a puzzle we have to solve each time we work with a historic building.

So, you now have a dual specialization: theaters and heritage?

D.Sh.: At a certain point, theaters began to move into the background, but about 7 or 8 years ago Oleg and I asked ourselves what we were really most interested in doing – and it turned out to be theaters and cultural heritage sites. After that decision, everything gradually changed over the course of two or three years: we once again began designing theaters, joined the team of authors working on the national code of practice for theater buildings (Code of Practice 309.1325800.2017 “Theater and performance buildings. Design standards”), began giving lectures at MARHI on theater design, and taking part in various forums and exhibitions.

Our real strength is our expertise in designing dozens of very different theaters – including such unusual ones as Kuklachev’s Cat Theatre or a Shadow Theatre. An understanding of theater technology, on the one hand, requires strict adherence to certain conditions, but on the other hand it opens up virtually boundless possibilities for innovative solutions.

O.Sh.: Designing a theater is always an experiment. The constraints of the site or the specifics of the existing building, the director’s creative method, technical and regulatory requirements, auditorium capacity, acoustics, sightlines, interior design – all of this layers together and produces a result that often has very little to do with the original brief.

D.Sh.: The process of designing a theater is like overlaying tracing paper sheets, each one representing a specific set of requirements. We keep aligning all these “layers” until the optimal image of the future building begins to emerge.

O.Sh.: Every time we discover something new – and that’s what makes our work so inspiring. Every new project is a challenge.

D.Sh.: The complexity of theater buildings conceals huge potential for optimization. If you simply add up the areas of all the necessary rooms, you will end up getting enormous construction costs – but in practice there is almost always the opportunity to reduce them, sometimes even by half, through multifunctionality or rational use of space. That’s what we did back in Sevastopol: we were able to reduce the total area of the Yelizarev Dance Theater building from 20,000 to 10,000 square meters. And that means a substantial saving not only in construction costs, but also in the building’s future operation.

We rarely take on someone else’s concept design. If we are invited to join a project, it is usually the exception rather than the rule. It requires some extraordinary circumstances: a landmark client or a high-profile architect. Normally, we develop the architectural concepts ourselves. And within our team this work is done collectively. When a request comes in, we determine who will oversee the project and which of our in-house architectural studios will take it on. We decide this among ourselves based on workload and project specifics – I usually handle new construction, while Oleg focuses on restoration and reconstruction. Another important factor is who has developed the closer, more trusting relationship with the client: we don’t see clients as customers, but as partners in the realization of a project. From that point on, project management and responsibility rest entirely with the supervising partner. Of course, we are both aware of all ongoing projects; together with our department heads we discuss them at meetings and search for solutions together – but making the final decisions always remains with the project supervisor.

O.Sh.: Sometimes we organize an in-company competition and invite several studios at once to prepare proposals, which we then analyze together and select the best solutions. We like to maintain a lively, creative atmosphere in the team, because there isn’t as much pure creativity in our profession as we would like. Only occasional flashes against the background of long and difficult project work.

MB-PROJECT carries out comprehensive design: including expert reviews, working documentation, and on-site supervision. Our employees are deeply immersed in the process, and it’s useful for them to switch gears now and then, listen to the “muse”, and argue among themselves.

D.Sh.: An interesting experience emerges when two different teams are brought into the same project. For example, on complex cultural heritage sites we involve two architectural groups: one specializing in restoration, and the other in new construction and reconstruction, and we suggest that they work together. This way they exchange competencies: the restorers begin to better understand the general construction regulatory framework, and the architects learn to value authenticity.

And how many departments are there in your company overall? How many employees do you have?

D.Sh.: A little over 70 specialists. Right now we’re in a phase of growth and continue to expand. Over the past two years we’ve increased our staff by 20–30 people. At the moment we have three architectural studios and two architectural-restoration studios, a structural engineering bureau, and a small engineering department. We act as general designers, and we have a large number of chief project engineers who perform project management functions.

O.Sh.: We have our own theater technology department. This is an extremely rare thing for an architectural office. Usually, specialists in theater equipment work for the companies that supply this equipment. As a specialized design organization, we have brought together highly qualified experts in this field, which allows us to combine equipment from different manufacturers within a single project and achieve the highest-quality solutions for equipping auditoriums – thus meeting the very highest demands of theater directors and their teams.

These days everyone complains that it’s hard to hire competent architects, but apparently putting together two teams of restorers is even more difficult. How do you manage to pull a stunt like that?

D.Sh.: You’re right. Unfortunately, the field of restoration is not in the best shape at the moment. Long-standing design institutes are closing. There are problems in educational institutions. However, two years ago we managed to assemble a professional team of restorers. Previously we had several specialists on staff and additionally engaged outside companies as subcontractors. Last year we were able to open a second specialized architectural-restoration studio.

You opened a branch in St. Petersburg. Why did you need another physical office?

D.Sh.: In St. Petersburg we are working on a huge project that includes 62 buildings that form part of the Botanical Garden ensemble. It is a unique complex with greenhouses, research buildings, and a museum. To coordinate the work of the design teams in Moscow and St. Petersburg, we needed an office and a design group in the nation’s Northern Capital.

O.Sh.: As it turned out, there are very few specialists in Russia who understand how greenhouses are designed and built. So we had to immerse ourselves deeply in this area as well. There are multiple nuances and complexities: glazing, ventilation, condensate drainage… the list could go on and on. But it is a very interesting field of design, with many “hidden reefs” and complex professional challenges.

D.Sh.: Working on unique projects attracts highly qualified specialists to our team – people with whom it is a pleasure to work on complex projects. Together we create an excellent, positive atmosphere in the office, which we value greatly. We believe that only in such conditions can good architecture be created!

Dmitry Shurygin and Oleg Shurygin, partners of MB PROJECTCopyright: © MB-project

Odintsovo school-gymnasium for 1,080 students with an extension for a pool block (Moscow region, Odintsovo, microdistrict 5–5a, Marshal Krylov Boulevard, 20)Copyright: Photograph provided by MB-projectOdintsovo school-gymnasium for 1,080 students with an extension for a pool block (Moscow region, Odintsovo, microdistrict 5–5a, Marshal Krylov Boulevard, 20)Copyright: © MB-projectMoscow Children′s Theater of ShadowsCopyright: Photograph provided by MB-project mos.ru" title="“School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya

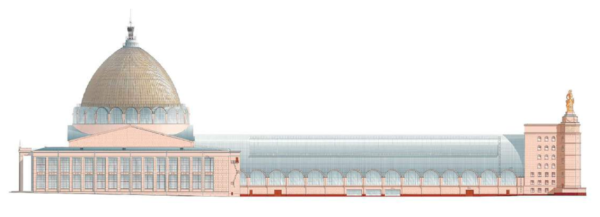

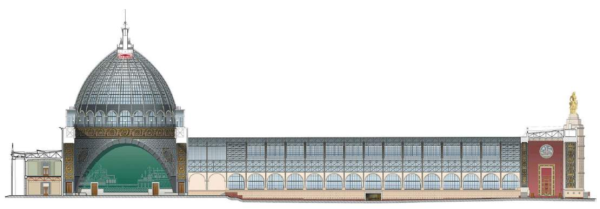

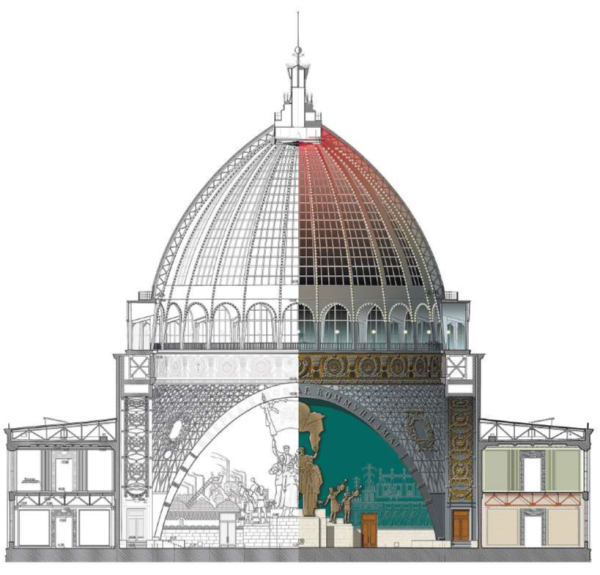

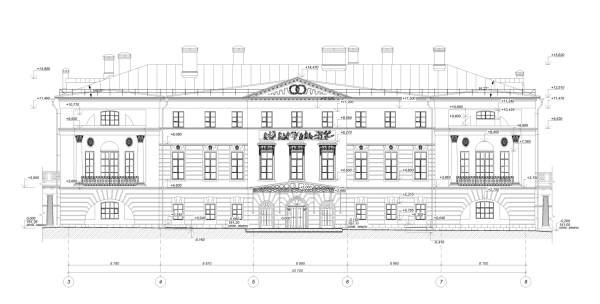

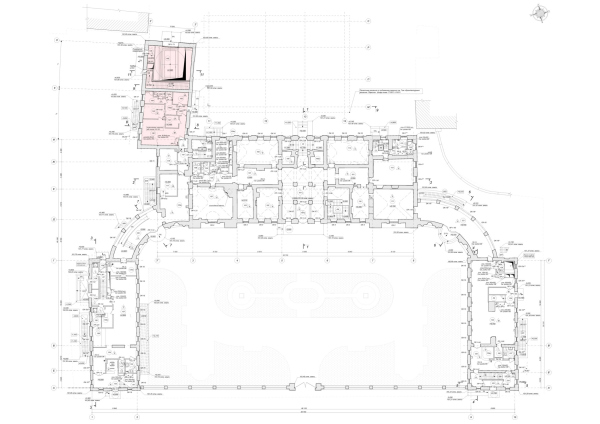

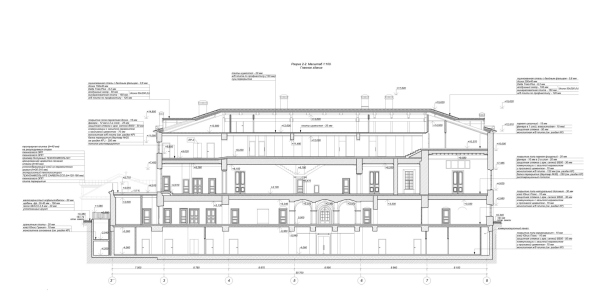

Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru"> “School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya

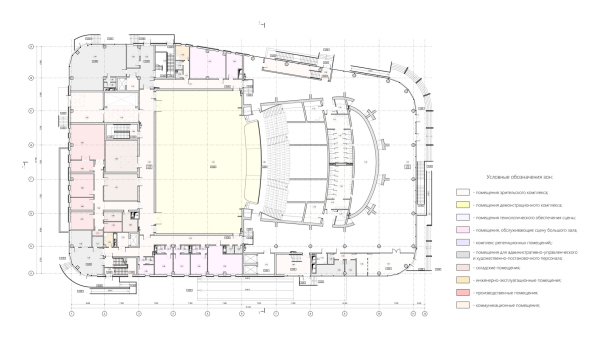

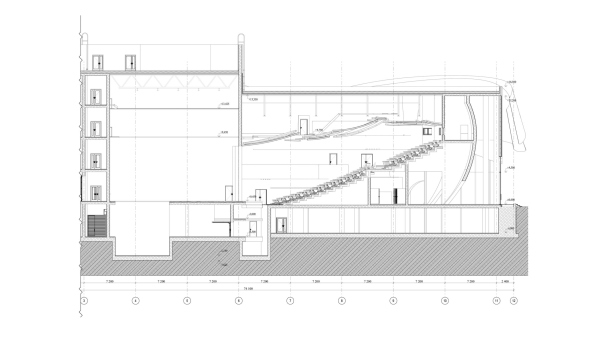

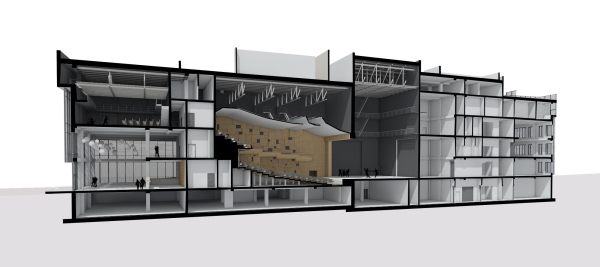

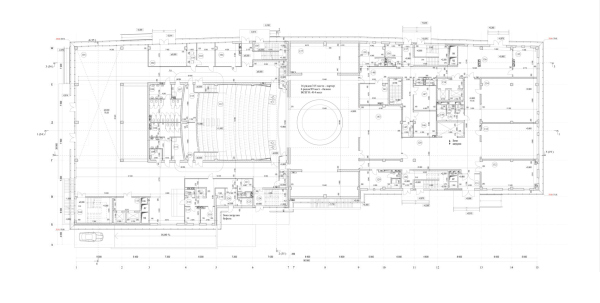

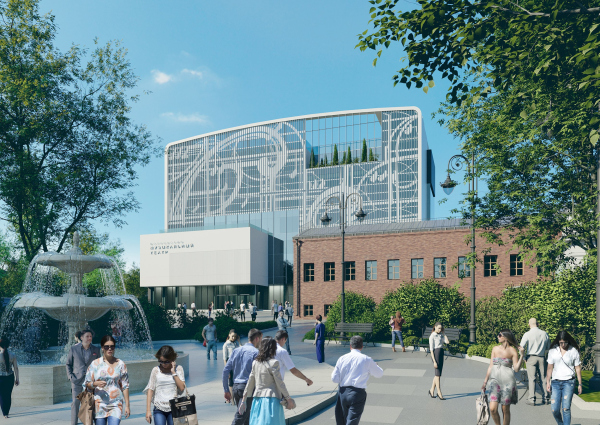

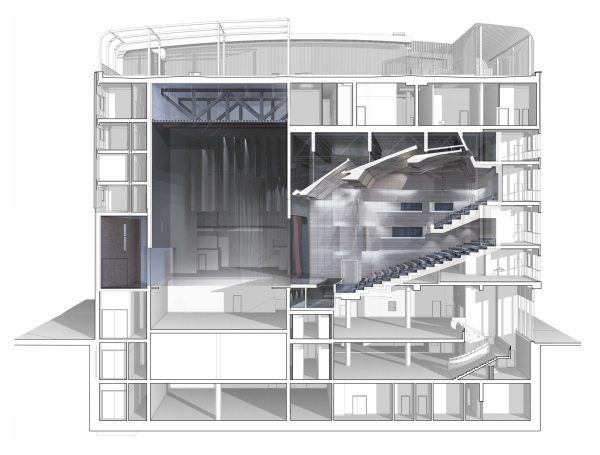

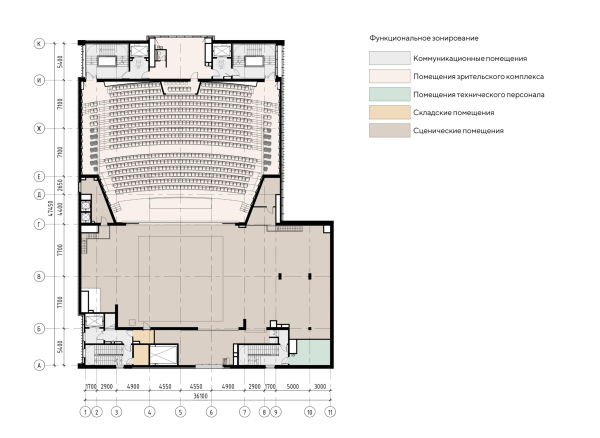

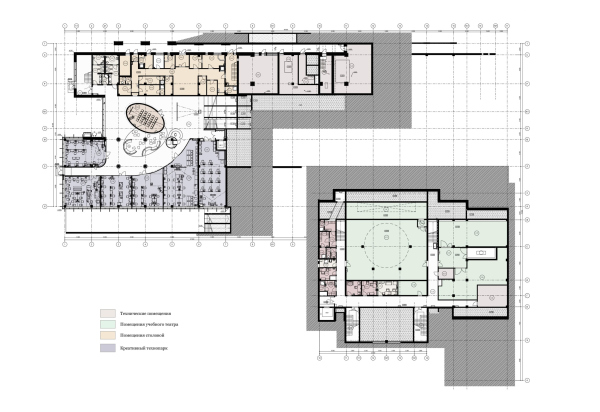

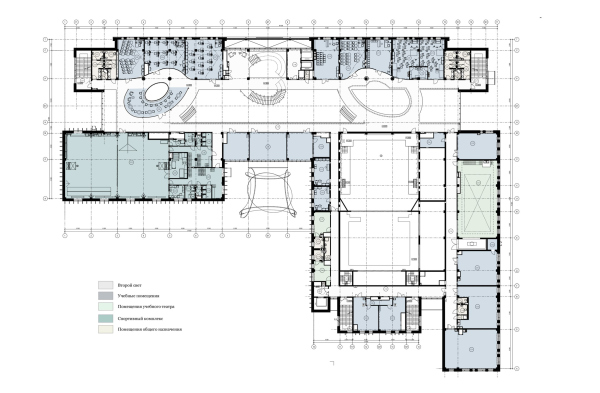

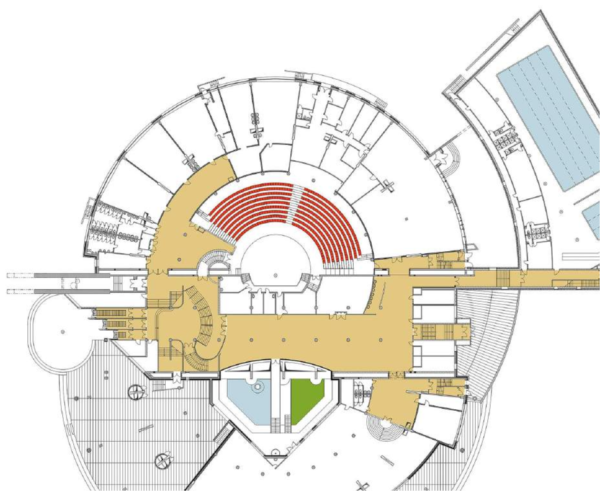

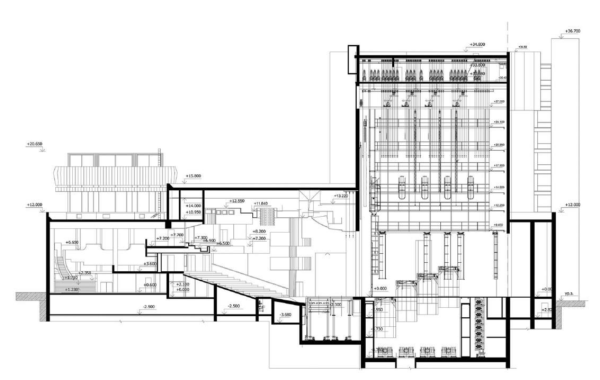

Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru mos.ru" title="“School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru"> “School of Contemporary Play” Theater on TrubnayaCopyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ruKuklachev Cat TheaterCopyright: © MB-project CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Moscow Children′s Book Theater “Magic Lamp” Copyright: Photograph: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0"> Moscow Children′s Book Theater “Magic Lamp”Copyright: Photograph: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0 CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Natalia Satz Children Music Theater Copyright: Photogrpah: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0"> Natalia Satz Children Music TheaterCopyright: Photogrpah: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0A reconstruction project. Visualization of the auditorium. Natalia Satz Children Music TheaterCopyright: © MB-projectA reconstruction project. Visualization of the auditorium. Satz Children Music TheaterCopyright: © MB-projectA reconstruction project. Visualization of the foyer. Natalia Satz Children Music TheaterCopyright: © MB-projectNatalia Satz Children Music Theater. Experimental hallCopyright: Photograph: Elena Lapina / Moscow State Academic Theater named after Natalia SatzA reconstruction ptoject. Longitudinal section. Natalia Satz Children Music TheaterCopyright: © MB-projectRestoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh FAL" title="Restoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh Copyright: Photograph: A. Savin / FAL"> Restoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKhCopyright: Photograph: A. Savin / FALRestoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKhCopyright: © MB-projectRestoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh. Longitudinal sectionCopyright: © MB-projectRestoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh. Crosswise sectionCopyright: © MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky HouseCopyright: Photograph provided by MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky HouseCopyright: © MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky HouseCopyright: Photograph: provided by MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky HouseCopyright: Photograph: provided by MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky House. The main building. Facade in axes 3-8Copyright: © MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky House. Plan of the 1st floorCopyright: © MB-projectReconstruction of the Bobrinsky House. Section 2-2. The main buildingCopyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Academic Dance Theater named after V.A. Elizarov Copyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Academic Dance Theater named after V.A. Elizarov

Copyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Academic Dance Theater named after V.A. Elizarov Copyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Academic Dance Theater named after V.A. Elizarov. Plan of the 1st floor

Copyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Academic Dance Theater named after V.A. Elizarov. Section 2-2

Copyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Theater of the young spectatorCopyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Theater of the young spectatorCopyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Theater of the young spectatorCopyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Theater of the young spectator. Section viewCopyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Theater of the young spectator. Section 1-1Copyright: © MB-projectSevastopol Theater of the young spectator. Plan of the 1st floorCopyright: © MB-projectThe new building of the Moscow Musical Theater in the Hermitage GardenCopyright: © Reserve Union, MB-projectThe new building of the Moscow Musical Theater in the Hermitage GardenCopyright: © Reserve Union, MB-projectThe new building of the Moscow Musical Theater in the Hermitage Garden. 3D section viewCopyright: © Reserve Union, MB-projectThe new building of the Moscow Musical Theater in the Hermitage Garden. Plan of the 3rd floorCopyright: © Reserve Union, MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. Evening view of the building from a birds-eye viewCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Yaroshchuk / provided by MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. SectionCopyright: © MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. View of a curved staircase suspended from cable-stayed structuresCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Yaroshchuk / provided by MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. The interior of the recreation area overlooks a light shaft with glass partitions.Copyright: Photograph © Dmitry Yaroshchuk / provided by MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. Atrium spaceCopyright: Photograph © Dmitry Yaroshchuk / provided by MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. Longitudinal sectionCopyright: © MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. Plan of the 1st floorCopyright: © MB-projectSiberian State University of Music and Theatre Arts in Kemerovo. Plan of the 3rd floorCopyright: © MB-project

|

mos.ru" title="“School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya

Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru">

mos.ru" title="“School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya

Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru"> mos.ru" title="“School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru">

mos.ru" title="“School of Contemporary Play” Theater on Trubnaya Copyright: Photograph: Press service of Moscow Mayor and Government. Evgeny Samarin/ mos.ru">

CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Moscow Children′s Book Theater “Magic Lamp” Copyright: Photograph: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0">

CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Moscow Children′s Book Theater “Magic Lamp” Copyright: Photograph: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0"> CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Natalia Satz Children Music Theater Copyright: Photogrpah: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0">

CC BY-SA 4.0" title="Natalia Satz Children Music Theater Copyright: Photogrpah: Shakko via Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0">

FAL" title="Restoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh Copyright: Photograph: A. Savin / FAL">

FAL" title="Restoration of the Cosmos Pavilion at VDNKh Copyright: Photograph: A. Savin / FAL">