|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 04.09.2025 | |

|

Water and Light |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Dmitry Ostroumov | |

| Studio: | |

| Prohram Studio | |

|

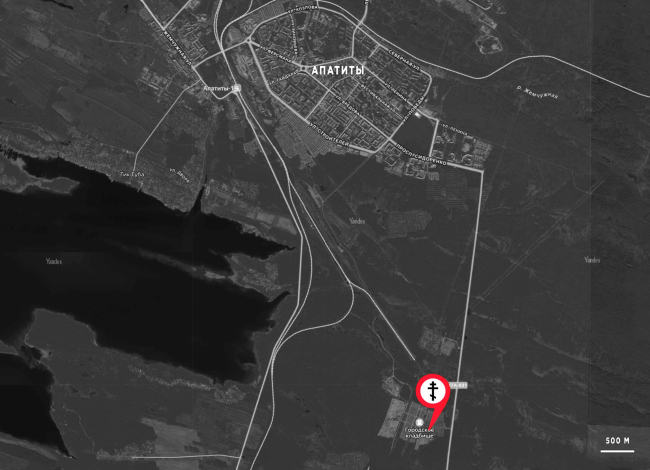

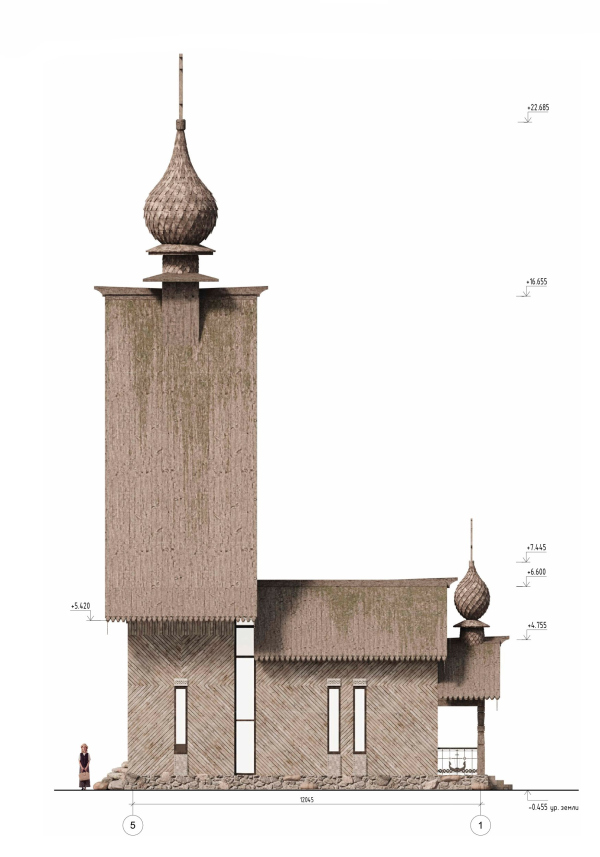

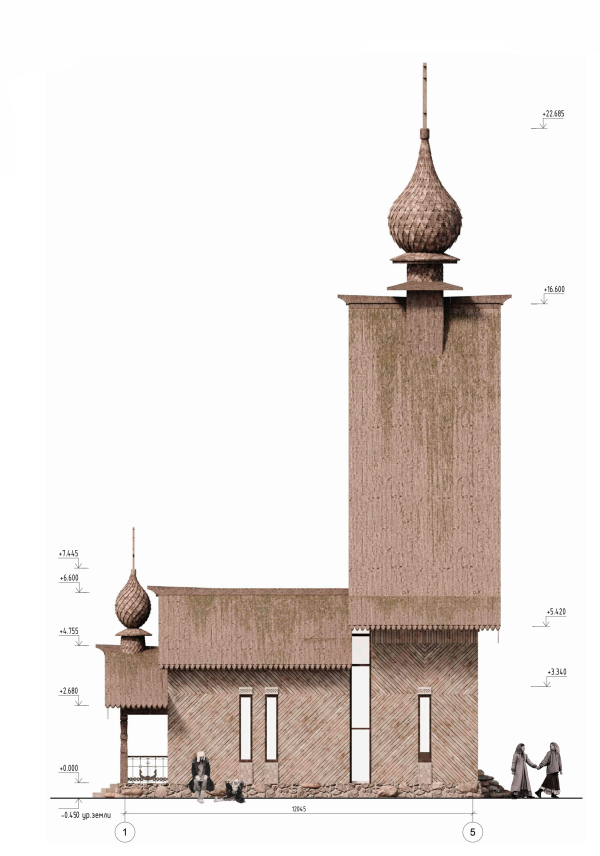

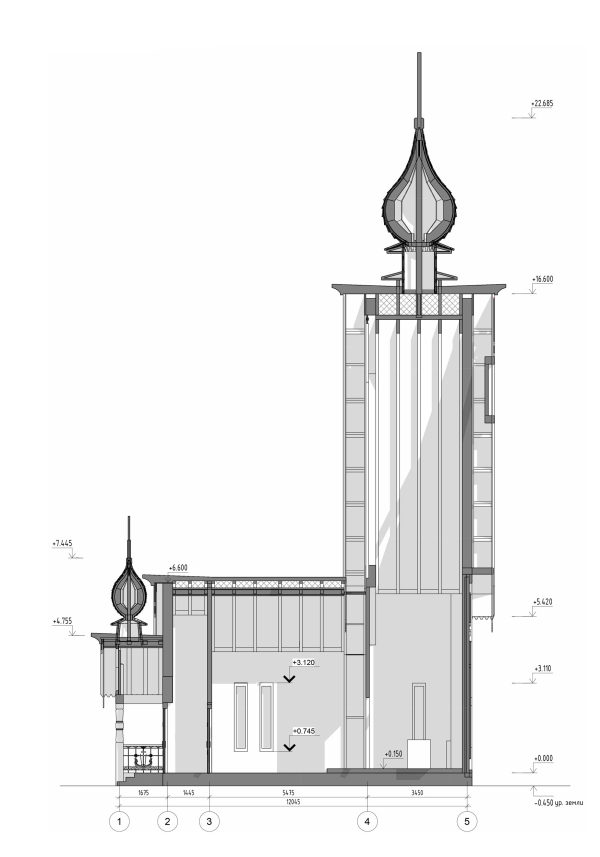

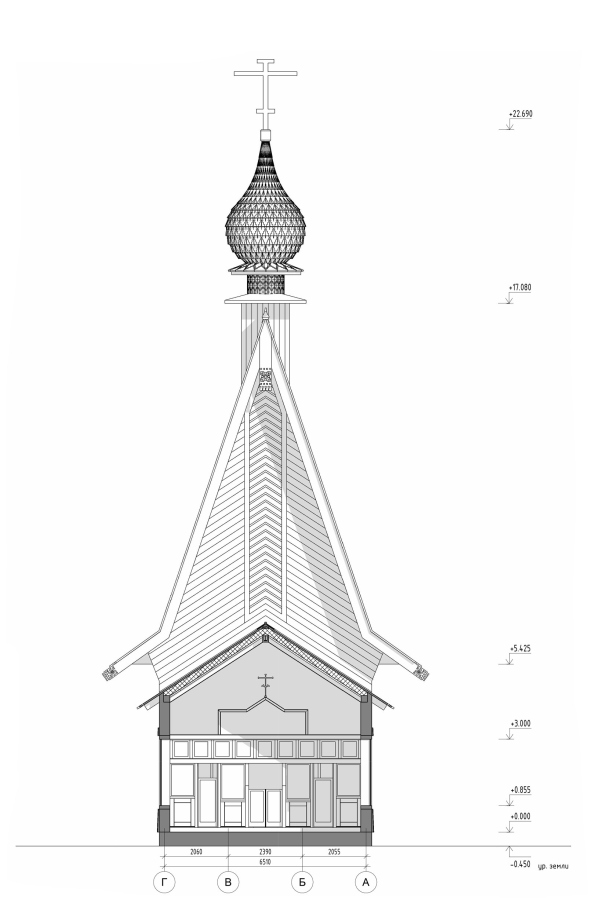

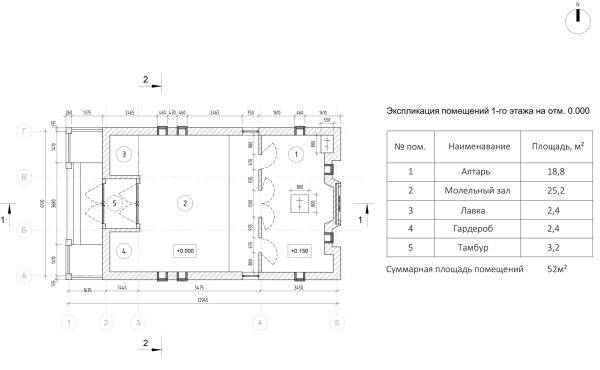

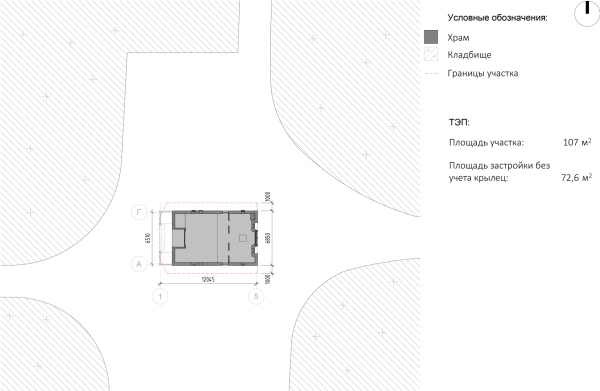

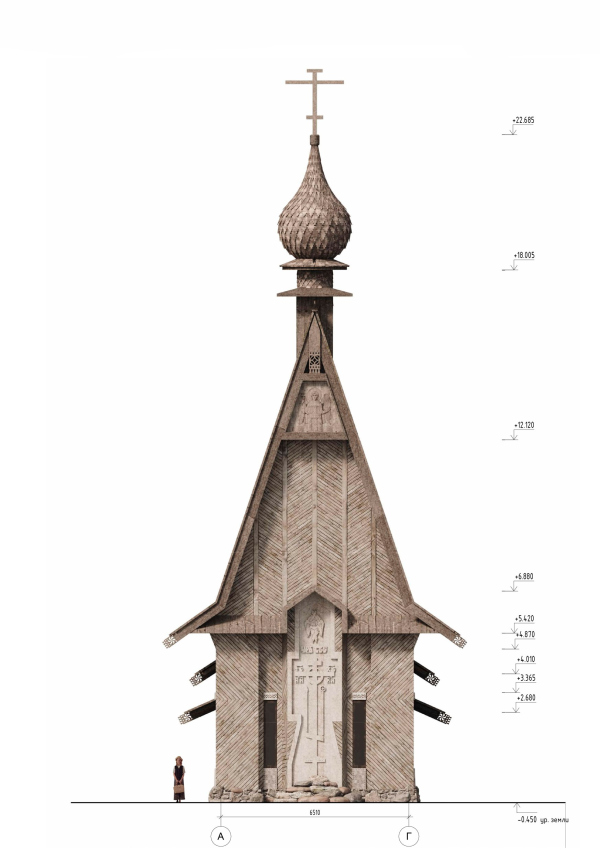

Church art is full of symbolism, and part of it is truly canonical, while another part is shaped by tradition and is perceived by some as obligatory. Because of this kind of “false conservatism”, contemporary church architecture develops slowly compared to other genres, and rarely looks contemporary. Nevertheless, there are enthusiasts in this field out there: the cemetery church of Archangel Michael in Apatity, designed by Dmitry Ostroumov and Prokhram bureau, combines tradition and experiment. This is not an experiment for its own sake, however – rather, the considered work of a contemporary architect with the symbolism of space, volume, and, above all, light. The project of the church of Archangel Michael in Apatity, presented by Prokhram, was recently recognized in Novosibirsk with two awards: one of the “Golden Capitels” and the so-called “Hamburg Score”, a ranking of architects participating in the competition. And this means that the majority of professionals who submitted their projects to the competition – since voting for one’s own project is, of course, not allowed – voted in favor of this particular project.  Dmitry Ostroumov , Prohram Studio We were significantly constrained by the size of the site. In other words, the building’s plan represents the maximum possible footprint. At the same time, the task was to make the church visible from the highway connecting the city and the airport. The highway is separated from the cemetery, where the church is located, by a forest. So we tried to stretch it upward, so that the light and the dome would be visible from the highway above the low trees, thus drawing the attention of passing drivers. In this way, the functional task of shaping the architectural volume in its specific environment came together with symbolic imagery. Nevertheless, the solution, although to some extent dictated by practicalities, turned out to be exceptionally beautiful. The altar table – the most important part of the altar – received above it a soaring space that can be regarded as an expression of reverence for the sacred place. It is, as can clearly be seen in cross-section views, entirely non-functional. There is no practical need for it; which means it has a solely symbolic meaning. It is astonishing that no one had thought of this before: since the altar is the most important part of the church, why not highlight it with a distinct, prominent volume visible from afar? In fact, one might say that in our time someone has finally thought of it. Although, in my amateur opinion, in most cases it was thought of incorrectly. The point is that in later times, in the 19th and 20th centuries, there gradually spread the practice of turning ancient churches into sanctuaries, while the later refectories appended to them became the church naos proper. This happened to the 16th-century cathedrals of the Nativity Monastery in Moscow and the Anastasia-Epiphany Monastery in the city of Kostroma… The worshipper there no longer has the opportunity to “touch antiquity”; on the other hand, one might assume that antiquity was “honored” by turning it into sanctuary space. Although, to be honest, there does not seem to be much reverence in such an act. The exclusion of the parishioners from the ancient church – yes, but that is not the point now I am trying to make now. Alongside the practice of “enclosure” described above, the history of post-Byzantine Orthodox architecture knows, as a rule, churches in which the space above the solea is the tallest, while the altar is lowered to varying degrees. In the project for Apatity it is not quite the same. The altar is emphasized in terms of both volume and space, while the entire church is new, with no ancient and later parts – and the altar, the place where the sacraments take place, assumes the greatest role. This is unusual, but meaning-wise it seems more appropriate. I would go further and say that the symbolic dimension is thereby enhanced. Note the herringbone boarding of the exterior walls, which I earlier compared with the architecture of the Art Nouveau period – it spreads across the side walls of the tall altar volume like rays of the sun. This, without doubt, points to the bloodless sacrifice performed on the altar table during the liturgy as a kind of essential value. We see a “traditional”, familiar church, only somewhat more elongated upward; but its internal structure is sharpened and altered in a number of other ways. I would not say that the alteration of the presumed functions of the volumes in the composition of the traditional “ship” in this case was made to the detriment of the parishioners. In a northern cemetery church, what matters more than a vast space above the head of the worshipper is the trivial warmth, and a lowered ceiling helps preserve it. It also creates a certain “intimacy” feel, and this is the right quality during a funeral service, when serenity for those accompanying the deceased is more important than the emotionally charged aspiration of the naos space upward. As for warmth, according to the architect’s description, a frame construction is planned here, clad with larch plank siding, and with modern wind and thermal protection – ecowool, thin and efficient – beneath it. On the outside there is “traditional” wood, on the inside a thin layer of contemporary insulation. But what I especially like is how the project authors handled the windows and glazing. In the naos and in the sanctuary, the windows are not too narrow, but neither are they squat – they are vertical, clearly related to contemporary examples. We also see restrained windows. Above and below them, a stone ornament “stretches” them vertically. This echoes the stone cross on the outer side of the sanctuary. If we look again at the plan, we can see that the altar is not left entirely unmarked. It even has a tripartite structure, with the northern niche marked, as is customary, for the credence table. Only the three parts do not have the “rounded” contour, for which Patriarch Nikon and his followers once fought – the outline of the sanctuary plan is drawn with angular lines that underscore the “wooden” nature of the church building. I should note that this does not contradict any of the church rules that I know. The two windows of the eastern wall are set in recesses, and on the central projection the architects proposed to place a stone relief of the Golgotha cross, the symbol of Resurrection and eternal life. According to the author’s description, this is “a stone votive cross built into the wall”. At the present stage, while the project exists only as a concept, it is hard to say whether the cross will be embedded in the wall as a volume or whether the architects will confine themselves to a relief. This is a peripheral consideration, however. Externally the cross resembles the Golgotha crosses set into the walls of fourteenth- and fifteenth-century Novgorod stone churches, and also, of course, the roadside votive crosses once erected in Russia’s North. I cannot recall them being so “merged” with the body of churches – perhaps only with chapels. So here we see the architects transfer a motif from ancient stone construction into a contemporary wooden building. Above the entrance, on the porch façade, the cross is echoed by a wooden (!) relief of a cherub, one of the heavenly Hosts, whose leader, as is well known, is Archangel Michael. Let us return to the stained-glass glazing, however. There is not much of it, but the glass works in an interesting way, because it has been conceived both figuratively and symbolically. Figuratively: in the eastern part of the church building, at the junction with the altar, the architects placed a continuous glass band that encircles the walls and pitched roofs – an entirely modern solution, which calls to mind perhaps Anatoly Polyansky’s Church of St. George on Moscow’s Poklonnaya Hill, only there the glass bands form large arches in each wall, lighting the interior as a whole. Here, however, the stained-glass strip lights the solea and the iconostasis. Next, on the western gable of the altar volume – and let me remind you again that it is tall – there is another glass band, vertical, with mullions set in a herringbone pattern that echoes the boarding layout on the walls. The vertical is a large window illuminating the altar, especially in the second half of the day. Before sunset, the ray from it will fall on the altar table and, together with the light from the side windows, will probably create a mostly “conceptual” or “imaginary”, but still perceptible, luminous cross. At night – and we are speaking of a location beyond the Arctic Circle – the church, on the contrary, will glow from within, creating accents: in front of the entrance, at the junction of the church naos with the altar. And the arrow-shaped window above the altar will glow. One may see in it a spear or the flaming sword of the Archangel, but this is not the primary association for the authors. Instead, they placed at the forefront the story of the Miracle at Chonae. The story goes like this: near Hierapolis, the place where today tourists bathe in Cleopatra’s Pools at the foot of the hill with the martyrium of Apostle Philip, there stood in the 4th century – when Emperor Constantine had already baptized the empire but paganism remained widespread – a revered temple of Archangel Michael. To destroy it, the pagans dug new channels for two mountain rivers so that their joined current would sweep the temple away. Then, at the prayer of the elder Archippus, who had long served there as sacristan, the Archangel Michael appeared and, striking the mountain with his staff, opened a cleft into which the waters rushed, sparing the temple. Thus, the window represents the stream, or, more noticeably, two merging streams. One may imagine the stained glass of the lower section as the divided streams, only they “flow” upward and, merging at the ridge, meet the altar window, which “flows”, like the thoughts of the parishioners and the souls of the dead, one may imagine, toward heaven. It may also be understood as light issuing from the altar – an idea also echoed in the arrangement of planks on the side facades. The volume of the altar thus appears to be “wrapped” in rays emanating from the altar itself. The architects, in essence, have given a figurative visualization of the soul’s ascent. And they have done so without any direct depictions, not literally, but rather emotionally, and by modern means. Now, a few words about those modern means. Creating contemporary architecture for an Orthodox church is still, unfortunately, quite a tall order, and only a handful dare to reflect on such imagery. Therefore: while to me the carved “towels” under the eaves of the altar seem overly conservative, and the placement of a large dome above the porch somewhat unexpected... Well, never mind all that – none of this matters. What matters is the successful experiment with the functional typology of volumes within the traditional silhouette, the ability to express sacred imagery not only through mimetic devices but also through architectural ones – above all, through light per se. As well as the architects’ ability to “stitch” the dedication of the church into a form almost devoid of visual literalness. I am speaking, of course, of the glass “arrow” on the western façade. By day, the association with a water stream is obvious. And at night... …At night each will see what their eyes will want to see: some a flaming sword, others a host of souls rising from the earth toward heaven, merging with the Northern Lights. Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. The location planCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. The north facadeCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. The south facadeCopyright: © Prokhram bureauChurch of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. Longitudinal section viewCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. Cross-section viewCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureauChurch of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureauChurch of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. Floor planCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. The master planCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. The west facadeCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in Apatity. The east facadeCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureau Church of Archangel Michael in ApatityCopyright: © Prokhram bureau |

|