|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 14.08.2025 | |

|

A Roadside Picnic of Urban Planning Theorists |

|

|

Alyona Kuznetsova |

|

| Architect: | |

| Marina Egorova | |

| Studio: | |

| Empate Architectural Bureau | |

|

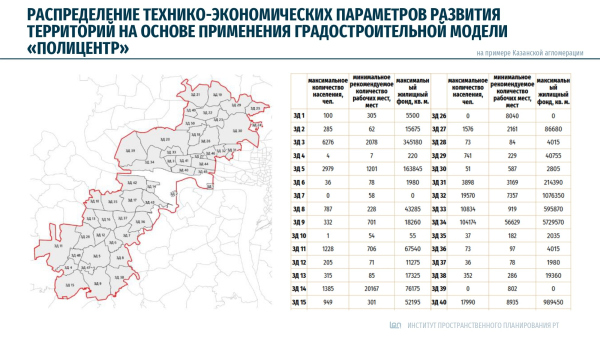

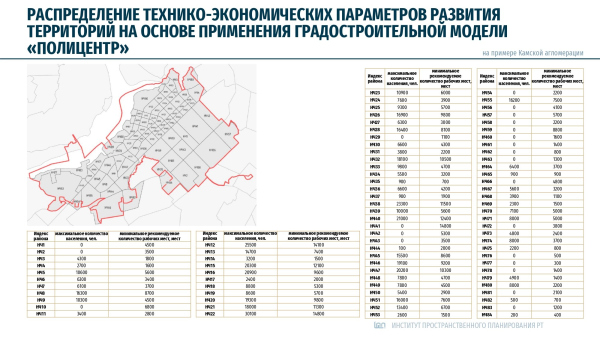

Marina Egorova, head of Empate Architectural Bureau, brought together urban planning theorists – the successors of Alexey Gutnov and Vyacheslav Glazychev – to revive the substance and depth of professional discourse. At the first meeting, much ground was covered: the participants revisited the theoretical foundations, aligned their values, examined a cutting-edge case of the Kazan agglomeration, and concluded with the unfathomable intricacies of Russian land demarcation. Below, we present key takeaways from all the presentations. Led by Marina Egorova, Empate Architectural Bureau is launching a series of discussions with professional urban planners. The first meeting took place during Arch Moscow 2025 and focused on the relevance of urban planning theory today.

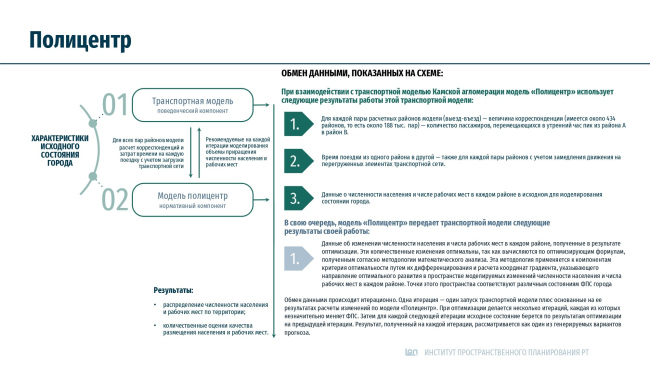

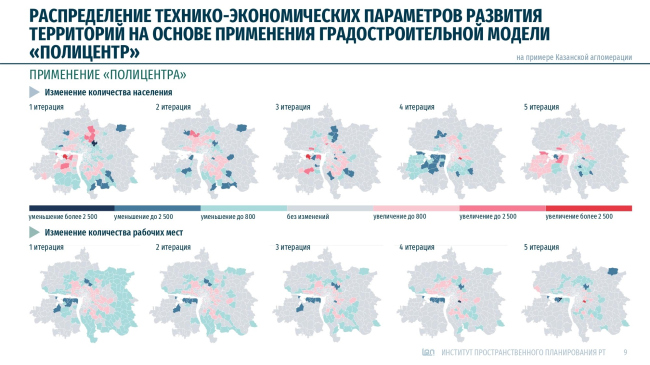

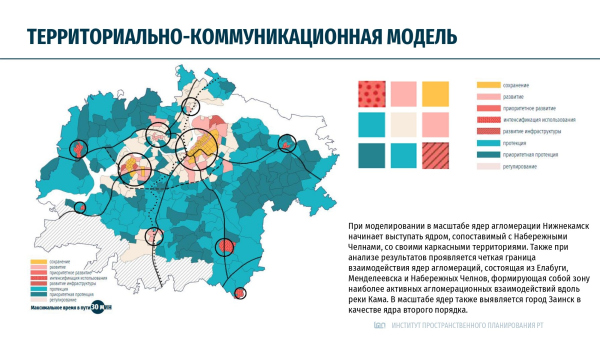

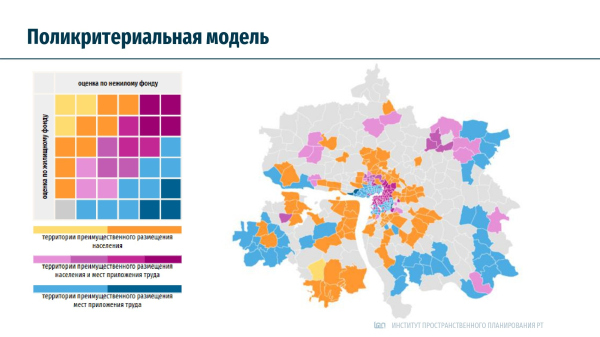

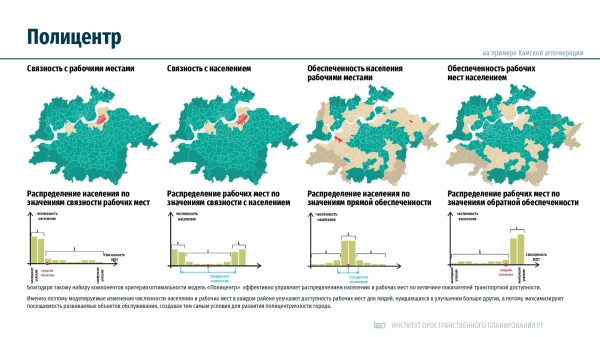

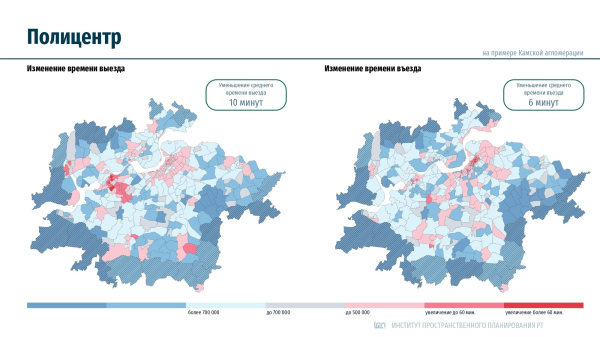

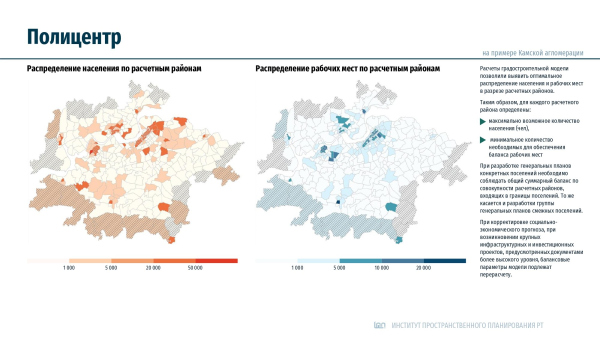

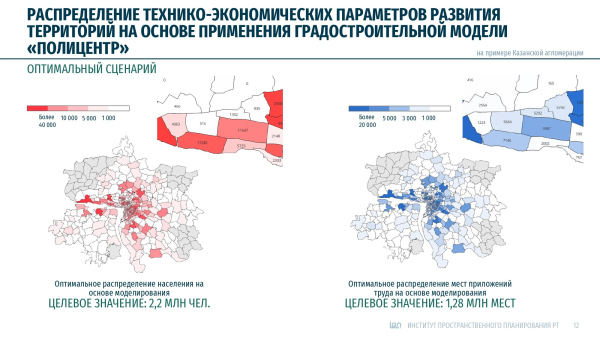

Roadside Picnic: Why Gather? Marina Egorova Architect/urban planner, founder and head of Empate Architectural Bureau The architectural community is constantly in search of new meanings and ideas, and is engaged in ongoing conversations about “the city of the future”. Conferences are held, and numerous publications are released. We see more and more examples of strategic development programs for cities, agglomerations, and even entire countries. However, all this seems to lack a scientific approach and depth. The immediate has pushed the intelligent and complex to the margins of discourse. Strategies are becoming increasingly similar to one another, often ignoring location and the ethno-cultural specifics of a region. Trends have replaced profound meanings and the understanding of how the primary beneficiary of creating and developing the urban environment – the human being – will live and work. There is a certain flaw in the way ideas are currently generated and decisions are made. In Soviet times, we had a clear understanding: here is the master plan, with a specific expiration date, and here is the production plan, whose implementation depends on the pace of factory construction and resettlement. But instead of developing the Soviet legacy, we are feeding off it and giving it a superficial facelift – in the form of public space improvements and the construction of “modern residential complexes”. The concept of sustainable development, which has been talked about at forums over the past ten years, does not work in Russia. I sincerely welcome the strategic development programs now being implemented in the Far East, in the Baikal Area, and in the Arctic. However, they must include other components that do not compromise the integrity of Russia’s territorial development. At the same time, the world is changing, and the economic model that our developers have grown accustomed to – and which has indeed worked well, mind – will no longer function; something new will emerge. The logic of city development will change, and there will certainly be an element of state governance in all that happens. But in what form will this state governance take shape? I thought it was important to start discussing this today with specialists who have something to say. Regretfully, the situation in Russia today is such that only a handful of specialists are able to talk about this. Our session today is indeed a “roadside picnic”. And my thought on the usefulness of our meetings is this: we are creating groundwork for the future, laying the prerequisites for the emergence of new urban planning ideas. Kirill Gladky Architect, partner and deputy general director of GA Architectural Bureau, advisor to RAACS, corresponding member of MAAM Several years ago, it began to feel as though professional discussions of urban planning theories had dried up. As a professional community, we are fragmented: each person is in their own specialized niche, and we rarely step out of it. We do not discuss the problems and objectives of development projects; we do not look for a common denominator between project practice and theoretical research. Instead, master plans and marketing studies are nearly always offered by the developers. In their world, the algorithms of commercial success and parameters of economic efficiency are all that matters. And there is a sense that urban studies based on big data are beginning to replace fundamental theory. There is a lot of talk about the future of cities. In my view, this is a form that so far has no real substance: scattered idealistic reflections, analytical marketing calculations, visual or PR provocations, works of publishing art, or business plans. However, what happens to these projects afterward – their life cycle, their eventual implementation, and what follows – is something that we do not entirely understand. The scope has also changed: if in the 2000s and 2010s we talked about long-term strategies, now the scale of our work and concepts is shrinking. These days, these are projects for integrated public space improvements, infrastructure development, or identifying urban potential for placing certain functions – mostly residential – but not a holistic understanding of a new environment. Some of this is happening because of external shifts in governance, but not as a result of movement from within the territory itself – I mean the principle of participatory planning, which was brought into our lives by Strelka KB through the Moscow Urban Forums, as well as by the Vysokovsky Graduate School of Urbanism. Atlases and the Life of Theories Oleg Baevsky Honored Architect of the Russian Federation, Professor, Academic Supervisor of the “Urban Planning” program at the Vysokovsky Graduate School of Urbanism, HSE University Our country was fortunate to have giants. The environmental approach of Alexey Gutnov, Vyacheslav Glazychev, Alexander Vysokovsky, and Grigory Kaganov formed the entire theoretical framework for understanding the development of spatial structures. Alexey Gutnov’s “frame-and-fabric” evolutionary model explained the mechanism of self-organization in spatial systems of any scale. There is a fundamental relationship between the accessibility of a territory and the intensity of its use – a simple concept worthy of being called “Gutnov’s constant”. This is what determines the evolutionary development of an urban planning system and what, in a remarkable way, formally links spatial structure to human behavior. As Gutnov discovered, the main trigger for the development of a city – for territorial growth, expansion, and the saturation of its framework – is a change in human behavior. What Gutnov also did was identify two super-characteristics. The first one is “cohesiveness” – how a given territory interacts with other territories and defines its role within that structure. The second one is the question of how intensively the territory is used. By comparing these two characteristics, we can identify existing imbalances in the structure of a city and suggest ways to remedy them. This is evolutionary development – a policy of soft power. You do not demand that a territory become something it cannot be. Alexander Vysokovsky’s uneven zoning model provided a more detailed version of Gutnov’s model. This “upgraded” model made it possible to identify specific nodes of systemic centers and elements within the framework. In parallel, models were being developed at the Genplan Institute of Moscow, such as Alexey Kaverin’s polycentric model. This was followed by work on the territorial/communication model. Unlike its predecessors, it was not an imitative model but an optimization one, because it was created to suggest solutions. We scaled this model up and applied it to the Kazan and Kama agglomerations, and it worked beautifully: the model allows forecasting the city’s development and optimizing its parameters. There is another direction as well. Anastasia Potapenko, a young researcher from Vladivostok, proposed using a set of models – the uneven zoning model, the territorial/communication model, and a few foreign models, such as Space Matrix and Space Syntax. At the same time, undergraduate students at the Higher School of Economics are working on creating a territorial/communication model for any city using open data. Even the poorest municipality today can afford to have this optimization model to help guide its development. To make it clear that behind these quantitative characteristics there is also a value system, I will give but one example. The territorial/communication model follows a very simple logic: the better a territory is connected to its population, the more attractive it is for locating workplaces and service facilities. And the better a territory is connected to workplaces and service facilities, the more effective it is – both economically and socially – for placing housing stock. Following this logic, one can derive a differentiation of territories by comparing accessibility and cohesiveness characteristics across several policy types. The first policy type features high levels of both density and connectivity – an exemplary environment, essentially the framework. This is, of course, a preservation policy. The second type is when one indicator is high (good transport accessibility) but the other is low (poor density), or vice versa. This is a development policy: there are unused resources. The third type features low values for both indicators. This is a protection policy – the territory must be provided with a socially guaranteed minimum. And in the center cell of this simple matrix are the “middle” territories. They are fine as they are, balanced, and can become whatever they choose – a policy of non-interference. These policies have a very clear ethical interpretation. Preservation policy – respect for elders. Development policy – demanding more from the strong. Protection policy – care for the weak. Non-interference policy – tolerance toward those who are different. Alexey Muratov Urbanist, publicist, partner at Strelka KB, former editor-in-chief of Project Russia magazine The foundation on which today’s urban planning rests is the base of “new urbanism”: from the American school – Christopher Alexander, Andrés Duany – to the European – the Crie brothers, Aldo Rossi. And, of course, the Soviet/Russian branch – Gutnov and Glazychev. I do not see any serious theoreticians emerging who could challenge this line associated with the contextual approach and the idea that we must learn from the historic city: it is resilient in every sense of the word, allows the creation of a continuous evolutionary field, and enables gentle, careful development of the environment. The city is a complex phenomenon, and there are many theories of the city. What Oleg Artemovich spoke about is more in the realm of formal theories based on mathematical models. But there are also critical and positivist theories whose applications extend to many different areas: urban society, urban economics, transport, territorial planning, and so on. The connection between theory and practice is often nonlinear. Theories that evolve into mathematical models acquire their own toolkit and are applied by specialists who may not even know where these theories came from or who developed them. Those who now, using GIS tools, identify the key points of the urban framework and then model the density and types of land use may be unaware that this subject was theorized in Russia by Gutnov and his colleagues, and in the UK by Bill Hillier, who developed the concept of Space Syntax. This is simply unnecessary, because GIS tools now provide “factory-packed” answers quickly – and you don’t need any theory to get them. Do you remember “Team Ten” – an association of late modernists that included Georges Candilis, Giancarlo De Carlo, and others who opposed the early modernists? They proclaimed: “Do as Le Corbusier writes, but not as he builds!” – thus highlighting the fundamental contradiction between everything related to manual labor and the reflective activity aimed at understanding abstract and general phenomena. That’s why I believe that the social, market, and political context of design influences urban planning more than any theories. And if we are talking about theories that influence professionals, then any project is a theory. When my colleagues from DOM.RF and Brusnika and I developed the standard for comprehensive territorial development, guided by the principles of “new urbanism”, what we ultimately created was essentially a theoretical work. However, the scope of its practical application turned out to be very limited because sustainable development directions are currently anything but a priority. The absolute priority was to build 100 million square meters of housing per year. Accordingly, our main task was to ensure the pace and volume of housing construction. This is, in principle, also a worthy goal, but it conflicted with ours, and that made life harder for us: in practice, we could not work with the developers. When we made master plans according to the standard we had developed, they would just go and say: “No, the density here is too low, there are too many streets and other public spaces. This option is a no-starter; we’ll go to someone else”. As you can see, theory can be both a plus and a minus for an architect, planner, or urbanist, for that matter. Sometimes it significantly limits one’s freedom of choice. And now, I must admit, we are already moving away from this standard a bit – life forces us to be more flexible and adaptive. Axiology of Brusnika Vasily Bolshakov Head of the Master Plan Department at the development company Brusnika, graduate of the Ŕđőčňĺęňîđű.đô program. Brusnika steadfastly implements in its projects the solutions set out in the comprehensive development standards: we both participated in the creation of these standards and are constantly improving them in practice. For us, this is an unquestionable value that we bring to life in the urban environment. At the same time, we are open to experimentation. In this sense, Brusnika is a kind of urban planning laboratory on a national scale: we are already present in thirteen regions. Within Brusnika, there is a values document called the “Product Policy”, which company architects are expected to follow. Five points in it are dedicated to urban planning issues. The key point for us is spatial integrity. When a developer takes on a particular site, they often think only within the boundaries of that site, and not an inch beyond it. In the rush to develop their own piece of land, they overlook the context and forget about integrating the development into its surroundings, and creating a coherent environment. Brusnika takes a broader view and never focuses solely on its own plot. We think out of the box. Literally. Second is segregation and division. We try to avoid putting up fences or other barriers between land holdings whenever possible. We see our task as stimulating integration processes within the area being developed. For this, we also use topology. People should be able to move freely across the territory, meet, and communicate with each other. Third is seamlessness – creating a barrier-free environment. Fourth is infrastructure. It is important to create it in advance. Today, we prioritize building infrastructure facilities, not only essentials like kindergartens and schools but also those that provide recreation and jobs. All this is so that the new block or district can develop a life of its own. Finally, fifth is density – not at any cost! We always look for a balance between density and the aesthetic qualities of the development. Density is not a qualitative characteristic; it is an economic indicator. Agglomerations of the Republic of Tatarstan Oleg Grigoryev Architect and urban planner, Director of the State Budgetary Institution “Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan” Several years ago, I began organizing the Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan. It is responsible for the master plans of all the region’s agglomerations – Kazan, Kama, and Almetyevsk. It was obvious that without relying on a solid theory, achieving the desired balanced development of a sustainable territory would be impossible. That is why we assembled a strong team: theorists Oleg Baevsky and Alexey Kaverin, plus a group of mathematicians and programmers. As a team, we managed to bring to a software product the theory that goes back to Gutnov, was developed by Oleg Baevsky, and had long been practiced at the Moscow General Planning Institute. Now we are applying it in Tatarstan. In the end, we obtained three models: the territorial/communication model, the multi-criteria model, and the polycenter. The territorial/communication model provides a general assessment and development policy for districts. The multi-criteria model evaluates territories based on the development of residential and non-residential functions. The polycenter provides specific recommendations for the volume of residential and non-residential construction in each calculated district. All of this works in conjunction with the transport model, but that is a separate theoretical field. The polycenter works closely with the transport model and addresses a simple question: how to optimize the placement of jobs and housing across large territories? This is a non-trivial task: one can spend a long time calculating and optimizing the transport network in the transport model, but it is also necessary to approach it from the other side. How can we optimally distribute the population across the territory so that the transport system functions well and sustainable development occurs? The polycenter is based on the standard evaluation of four indicators: connection to the population, accessibility of the population, connection to workplaces, and accessibility of workplaces. Over four iterations – as we transfer data from the transport model to the balance model – we achieve a certain optimization model. As a result, we get a set of specific recommendations for each calculated district of the studied territory: how many people can be accommodated here, how many jobs, and therefore how many enterprises. And all of this has a direct, I would say “linear” impact on concrete figures for each planning unit. Each such unit – a small patch on the map – receives clear recommendations: for example, here, in this specific location, this many square meters can be built and no more; here, this many enterprises must be placed, which will generate this many jobs. This is the absolute, straightforward application of theory. But it only works in the context of a growing population; with a declining one, it makes no sense. The model is embedded in the master plans of the agglomerations: figures are transferred into the parameters of functional zones within general plans and into land use and development regulations. From there they trickle down to the level of project planning, and so on, step by step – all the way to the so-called Urban Development Plan for a Land Plot). Parameters for each territory are approved at the republican level. To change them, one must apply to the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic – only it can amend the document. Since the master plan does not yet exist in the legal framework, the Cabinet of Ministers decided to call it the “Comprehensive Scheme of Social and Economic and Spatial Development of the Kazan Agglomeration”. This is an applied document: not theory, but absolutely concrete requirements for the development of each site, all aimed at achieving balanced growth. Thanks to the “Comprehensive Scheme of Agglomeration Development”, we managed to reduce by more than half the volume of construction that had been planned on the periphery and was creating imbalances. It is not enough to say that we adhere to a certain ethic – you need to translate it into concrete figures, have it approved by the leadership, and then enforce it strictly. In Tatarstan, a separate law on urban development monitoring was drafted. It allows the institute to request data and monitor the situation. Each year, a report is delivered to the leadership’s desk showing where we are headed and how urban planning policy is being observed. We had to centralize the entire urban planning function at the regional level. In order to do that, we carried out an expert review of absolutely all planning documentation produced in the republic. Yes, it is a large and serious task indeed, but it has to be done. The Cytoplasm of Undivided Land Andrey Gnezdilov Architect, co-founder and first deputy director of Ostozhenka Architects The work begun by the Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan is needed across our entire country. However, many people, including both practicing urban planners and think tanks, have overlooked one crucial detail: under capitalism, there is private land ownership, period. And in what we are used to working with and calling our urban planning theory, there was no private land ownership at all – simply because it was initially based on the Soviet economic model. A huge amount of work lies ahead in this cosmos of floating state property, in this whole cytoplasm of unpartitioned Russian land with fragments of someone else’s plots scattered within it. When Kirill Gladky and I were developing the “Street Design Code” for Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk, we encountered the fact that the red lines were somehow drawn along the edges of the roadway. The same thing happened in Novosibirsk: there are red lines 10 meters wide. And beyond those red lines lies terra incognita: literally nobody’s land, completely ownerless. We labeled it “Territory with undefined functional designation and ownership”. Moreover, the streetbeds themselves, the roadway, still turned out to be in the private ownership of some local “Avtodor” company. That is the miracle of the mismatch between our theories and the reality of the land! In Moscow, it would seem that the entire territory should be covered by Territory Planning Projects). However, we found out that this is just not the case! Fortunately, now the Integrated Territory Development mechanism has appeared. If the plots continue to be surrounded by this strange unpartitioned land, we will never bring them to order. We at Ostozhenka began our work in the city with the historic district of the same name. And in that historic district, before the revolution, everything was clear: parceling, house ownership, boundaries, and so on. Now we manage to reproduce this only in unique ways on unique territories, like those designated for renovation, for example. Because no Soviet microdistrict can be overlaid with a proper subdivision grid. And we are simply doomed, most likely, to continue living in this “collective farm”, because a collective farm field is very difficult to divide into private plots. There is a catastrophic lack of street density – as we know, street density even in Moscow is about 2.6 kilometers per square kilometer. This is directly related to land subdivision, because each boundary must lead to a street. In any organism there is a skeleton, a framework, and there is tissue. And if there is no living cell in the tissue, then it too will be lifeless. Why am I so obsessed with this subject? Because I see that not a single one of our current urban planning theories addresses it! How are we supposed to remake Soviet cities? How do we adapt them to capitalist reality? We don’t! There is no way to do that! But we must admit that our country with such a living tissue is unique in the world. Well, maybe North Korea as well. But nowhere else in the world is there such a miracle, where there exists land with no clear ownership. Discussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural Bureau Terrotorial/communication model. Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Multi-criterion model. Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Polycenter. Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of TatarstanApplication of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of TatarstanApplication of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of Tatarstan Application of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of TatarstanApplication of balance modeling in spatial planning of the Republic of TatarstanCopyright: Image © Oleg Grigoriev / State Institution Institute for Spatial Planning of the Republic of TatarstanDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural BureauDiscussion “Relevance of urban planning theory” at Arch Moscow, 2025Copyright: Photograph © Ekaterina Batalova, special for Empate Architectural Bureau |

|