|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 16.12.2024 | |

|

Competition: The Price of Creativity? |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Studio: | |

| Genplan Institute of Moscow | |

|

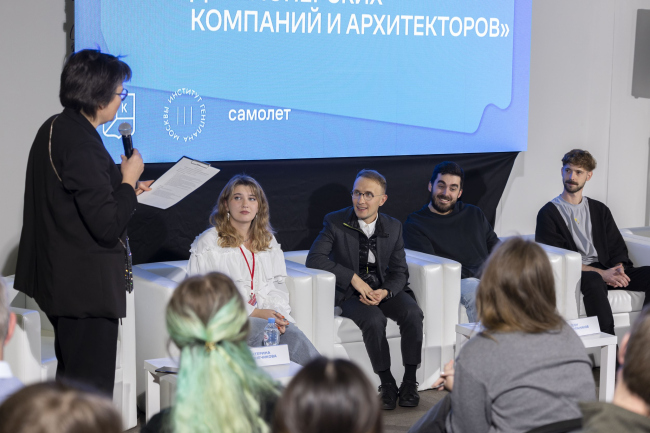

Any day now, we’re expecting the results of a competition held by the “Samolet” development group for a plot in Kommunarka. In the meantime, we share the impressions of Editor-in-Chief Julia Tarabarina, who managed to conduct a public talk. Though technically focused on the interaction between developers and architects, the public talk turned into a discussion about the pros and cons of architectural competitions. The public talk at the “Zodchestvo” festival in Gostiny Dvor was formally titled “Residential Architecture: Opportunities for Interaction Between Developers and Architects”. It featured three finalists from one competition – the contest for a large plot in Kommunarka – as well as Leon Pryazhnikov, Product Director of the “Samolet” Group, the sole representative from the “other side of the process”, meaning the developer.  Location plan for the concept of the urban area in Kommunarka, 2024Copyright: Image © Genplan Institute of MoscowGiven this setup, it seemed reasonable to steer the conversation from generalities to specifics, focusing on competition practices and asking relatively concise questions. I’ll admit, escaping the banal discourse on the virtues of competitiveness was nearly impossible, but some valuable points were indeed touched upon in the course of the discussion. At the very least, I take the developer’s comment that his chair “seemed about to catch fire underneath him” as a compliment. No chair ended up ablaze, and the conversation as a whole was calm – it was more of a collective interview in some respects. Here, we present it as a series of recollections and excerpts. A general takeaway from the knowledge and impressions gained: the architectural company IND now has 300 (!) employees. A significant number of master plans are being developed right now, while Lampa Community, in just three years since its founding, has worked on 85 projects across 30 regions, ranging from landscaping to spatial development. From left to right: Ekaterina Kuznechikova, Lampa community; Amir Idiatulin, IND; Daniil Kapranov, GA; Alexandra Danilchenko, K12Copyright: Photograph © Vladimir KudryavtsevMoving on: competition fees are laughable, yet competitions themselves – with their stress, deadlines, and chaos – are beneficial for skill-building under pressure, networking, and a touch of PR. Competitions are also useful for developers in improving their product. Some argue that by participating in competitions, architects essentially subsidize developers, working at full capacity without, shall we say, excessive compensation. In doing so, they pay for their own training, their staff’s development, and a bit of recognition. Overall, this aligns with what we already thought about competitions – only some points were reinforced. Still moving on: competitions are helpful when they have a clear organizational structure and a reward that, while not lavish, is at least adequate. It’s also important for organizers to guide the finalist participants working on projects, rather than leaving them to fend for themselves. From the participants, a clear application is required. Ideally, it should include a sketch. This makes sense: a sketch demonstrates both the desire and the ability to propose something coherent, perhaps even beautiful. It also allows, I presume, for weeding out those who submitted portfolios “for the sake of numbers”. No ideal competition format exists To start, I asked Leon Pryazhnikov why the Samolet company decided to hold an open competition with portfolio-based selection for the Kommunarka site. Was this approach recommended by Moskomarkhitektura – as we know happened in the early 2010s – or did the idea come from the company itself? The response was quite confident: “This wasn’t some directive from above; it’s simply our general approach. We’re now running various competitions for completely different purposes – public spaces, landscaping – seeking to foster competition in ideas, perspectives, and visuals”. – How long has your company adhered to this policy? Leon Pryazhnikov, Product Director, Samolet Group: Leon Pryazhnikov, Samolet Group. Session “Housing Architecture: opportunities for interaction between development companies and architects” at the Zodchestvo Festival 2024Copyright: Photograph © Vladimir Kudryavtsev“Business approaches go through cycles. Four years ago, nearly every master plan and façade for Samolet was handled by 3–4 architectural firms – we didn’t position it as a competition but rather as project work. The best master plan was selected, and the team behind it would then handle the façade, landscaping, and so on. Later, we realized that this approach took too much time. So, we began entrusting architectural work to single teams. And then we understood the need for competition. Today, we have strategic partnerships with certain firms, and we also have our own internal architectural studios within Samolet”. And we decided to add some external perspectives – that’s where a public, open competition like the one in Kommunarka comes into play. We believe there is no single best approach. Each situation calls for its own solution. For Kommunarka, where we have 300,000 residential units and 300,000 offices, it made sense to hold a large, open competition. For contests focused on public spaces or landscaping, a different format might be more appropriate. Of course, competitions take more time, but they yield more interesting results. However, to achieve those results, active involvement is crucial. That’s exactly what we’ve done: in Kommunarka, my colleagues worked closely with participants, guided them, answered questions, and ensured they felt supported. We also had assistance from colleagues at the Genplan Institute”. Creative Energy, Stress, and Deadlines The rationale for holding competitions from a developer’s perspective is clear. While they require additional time and resources for organization, they offer publicity (if the competition is open), a variety of solutions to consider, and valuable experience working with architects. Amir Idiatullin, IND. Session “Housing Architecture: opportunities for interaction between development companies and architects” at the Zodchestvo Festival 2024Copyright: Photograph © Vladimir KudryavtsevNonetheless, I’ve often heard architects say that competitions are exciting but extremely expensive – that the effort and time invested don’t pay off and can even push firms to the brink of bankruptcy. My attempt to delve deeper into this topic during the conversation wasn’t particularly successful – the participants were all competition enthusiasts who thrive on the creative adrenaline that competitions bring to their teams. The most vocal advocate for competitions was Amir Idiatulin of IND. Unsurprisingly, he seemed completely at ease in this environment, like a fish in water. Recently, he won one of the categories at WAF, and back in 2020, in collaboration with the Chinese company DA!, he won a competition to design a museum in Sichuan Province. Take note of his opening words when asked about participating in competitions – how often, and why? Amir Idiatulin, IND: “If I were simply invited to submit a commercial proposal for designing Kommunarka, I wouldn’t do it. There’s too much work, and working purely on commission isn’t interesting. A competition, however, is quite a different story. Competitions bring a vibrant atmosphere and are a major challenge for the team. There are strict deadlines, schedules, and uncertainty: will you win or not? I love competitions because they teach architects to think fast, meet deadlines, and deliver outstanding results.” – Have you always held this view, or did it evolve as your company grew? “Always. People ask me why our company grew – from 10 to 20, 30, 50 people, and now 300... Because this has always been our marketing strategy. Without competitions, it’s impossible to build a strong team, develop an interesting portfolio, or create valuable connections. Even if you don’t win, you do gain connections that help you push things forward”. – Do you differentiate between staff working on competitions and those working on commissions? Do you rotate them? “It’s best to rotate. Competitions sharpen skills, and afterward, employees can achieve far more. Someone who has handled the stress of a competition can perform three times better than someone who has only worked on commissions”. The youngest team in the competition was a consortium made up of Lampa Community and “Collective 12”. The latter is relatively new, formed during urban research for another competition organized by the Genplan Institute of Moscow, “Explore the City!” – where they won first place. During the discussion, it emerged that “Collective 12”, as a newly established group, had initiated participation in the Kommunarka competition, seeking partners with legal entity status. This led to many jokes, with Ekaterina Kuznechikova, founder of Lampa Community, repeatedly emphasizing that they are not just a legal entity but full-fledged contributors to the work. Let’s emphasize that as well. Actually, we already have, but it will not hurt to stress this one more time. Ekaterina Kuznechikova, Lampa Community: “In three years, we’ve achieved a lot. We actively work with developers across 30 regions, on 85 projects. We primarily focus on landscaping and spatial development. We also do master plans. We’ve participated in competitions, such as one in Kaliningrad. I must say, there are rewarding competitions and unrewarding ones. The unrewarding ones are those with minimal funding for work or an unclear, opaque organizational structure – those we try to avoid by all means. As for how we entered the Samolet competition, it was something of a romantic story between Lampa Community and Collective 12. A friend told me about a great team looking for partners to submit an application with. I thought it was a great idea but unlikely we’d pass the selection and get shortlisted. Then, when I found out we were indeed selected, I stared at my phone wide-eyed with surprise. For us, this scale is a colossal experiment, something very new. We view it as a platform for self-expression. We want to make a name for ourselves and prove that small architectural companies can also deliver great, high-quality work”. Aleksandra Danilchenko, BIM Manager, K12: “There was a working team, and we decided to give it a try <…> The project turned out to be a very rewarding experience. It really hones skills like strategic thinking, working under deadlines, understanding technical specifications, and figuring out how to adapt and refine things, and show creativity within them”. The most prominent architectural company among the Kommunarka finalists was GA, represented in the discussion by Daniel Kapranov, the project lead for the finalist design. He echoed his colleagues’ sentiments, emphasizing the benefits of competitions: one should seize any opportunity to participate. For competition teams, it’s better to include diverse staff members so everyone can experience the excitement and creativity of brainstorming. However, it’s crucial to recruit only those who genuinely want to work on the competition. Initially, a “core” team is formed, followed by others. Kapranov also highlighted the focus on mass housing, stating that GA joined the Kommunarka competition partly because of their interest in tackling mass housing as a challenge. The architect’s budget: competition as a “donation” – Does the fact that competitions don’t bring in much money bother you? Amir Idiatulin, IND: “In this case, we are sponsoring Samolet to improve the product. It’s not about money at all; the fee is laughably small. Other developers are ready to pay you significantly more right away to take on a project and prepare three options. If the city doesn’t approve, you prepare five more options…” – And how do you maintain the financial stability of your company? “Well, there are commercial projects. We have plenty of contracts with Samolet, too, for a fact. Last year, we had about 15 contracts for master plans. It varies each time. Competitions, however, are a sort of “donation” for development. Developers, by the way, gain more by organizing competitions than by simply contracting a project for a specific site”. A Positive Limitation? What stood out to me most during the discussion was Amir Idiatulin’s self-critical assertion that architects need to be financially constrained – they are “like women with a limitless credit card in a clothing store.” Amir Idiatulin, IND: “No matter how much money you give to an architect, it’s never enough. Let me explain why. It’s not that they’re greedy or love buying expensive things. No. It’s just that architects adore the design process as such. They will keep revising their decisions, ordering the best renderings from the best studios, and then redoing everything over and over again. It’s an endless process. In competitions, it’s particularly hard to draw the line. You feel you need to deliver the best possible solution you’re capable of. All competitions have practically left us in the red. I’ve never encountered a competition where an architect came out ahead financially. The bar keeps rising. Recently, we participated in a school competition and won the client over because we also made a video. Then there was another competition, and the client was like: “Where’s the video? Didn’t you make one for the previous competition?” The more you give them, the more they want. In our business, you have to learn how to make money and learn how to set a point of no return – when it’s time to stop, no more renderings!” Leon Pryazhnikov, a representative of Samolet, responded with the remark: “I get the picture! Essentially it means that the budget was inflated, and it needed to be cut!” Of course, this was a joke. He continued: “Listen, in any case, a competition, even for three concepts, will cost more than simply going out and ordering this concept directly. Moreover, a competition takes longer!” So, does it mean that both the client and the architects pay for creativity and experience in a competition? For us... Thus, a competition is a means of “professional development” for all parties involved. You don’t make money from competitions – in fact, you either earn a headache or experience. Experience, team drive and creativity, connections, fame – this is a rough list of the benefits that the efforts involved in a competition can bring to an architectural firm. All in all, this set of benefits is well-known, and everyone decides for themselves how strong the layer of subcutaneous fat in their company is to afford some exercise in competition. But wait! Fame – it seems that the participants in the conversation reacted particularly sluggishly to this concept. That is, yes, of course, but... The word NDA was mentioned more than once – initially in response to a request to discuss work on yet-to-be-published projects. But here, one can agree: after all, for the public competition of “Kommunarka”, we were promised the possibility of publishing the final projects. Permission to publish your projects is another major issue of our time. Much of the work done cannot be shown to anyone in architects’ portfolios due to restrictions. “I go to the client, show them our work, and they ask: hey, where’s the housing?” says Amir Idiatullin. “We have 10 housing complex projects in progress, but I’m not allowed to show a single one of them...” And IND is not the first to say this, for that matter. Leon Pryazhnikov countered: “Well, if you want to show it, how about this proposal: minus 60% of the fee, and you can show whatever you want!” He also joked, of course. But in every joke, there’s some truth, right? However, it must be acknowledged that the prize fees set by Samolet in the Kommunarka competition – 4, 2.5, and 1.5 million for the top three places, respectively – are by no means small compared to the average level of such prizes in the market. We also acknowledge that the practice of competitions, with its pros and cons, is a topic for more than one discussion. |

|