|

Published on Archi.ru (https://archi.ru) |

|

| 21.01.2025 | |

|

Sergey Skuratov: “By and large, the project has been realized in line with the original ideas” |

|

|

Julia Tarabarina |

|

| Architect: | |

| Sergey Skuratov | |

| Studio: | |

| Sergey Skuratov architects | |

|

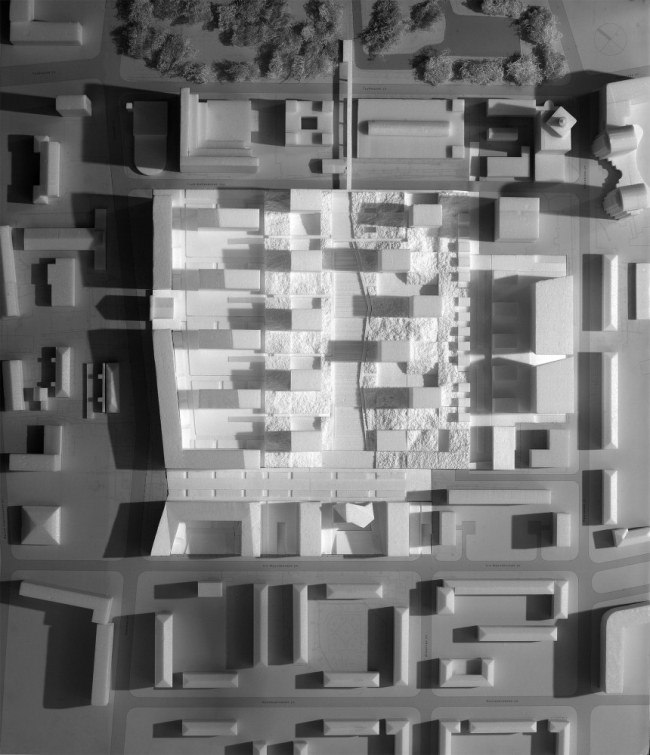

In this issue, we talk to the chief architect of Garden Quarters, looking back at the history and key moments of a project that took 18 years to develop and has now finally been completed. What interests us most are the transformations that the project underwent during construction, and the way the “necessary void” of public space was formed, which turned this remarkable complex into a fragment of a whole new type of urban fabric – not just at the horizontal “street” level but in its vertical structure as well. Following our own reflections on the place of Garden Quarters – completed in 2024 – within Moscow’s architectural history, we sit down with its chief architect Sergey Skuratov. This conversation does not aim to answer all of our questions – some details may have been forgotten, while others are impossible to forget – but we believe it offers some new perspectives on this seemingly well-known project. “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024. View of Block 3Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov ArchitectsArchi.ru: So, the project is complete, and the pond at its center has been filled with water – we’ve seen it. In the fall, it was partially drained. Will there be an ice rink eventually? Sergey Skuratov: At the final stage of development, the pond was slightly reduced at the request of the developer. In my opinion, that’s not a bad thing – it created more surrounding space and allowed for more trees. As for the ice rink – it was indeed designed but has not yet been realized. We provided for everything, down to the smallest details, including the steps that lead to it. The pond is about 60 cm deep, while an ice rink only needs 10 cm, and it requires a proper access point, which we also designed. In December, I learned that the rink might not be built. If that’s the case, it’s a big disappointment. I still hope that the developer – now the company Sminex – will reconsider their decision. The pond, in a way, provides a good starting point to discuss the project itself. Garden Quarters is a large and well-known project. What does it mean to you personally? This is the longest-running project in my career and for my company, which turns 23 this year. It lasted 18 years and reached the finish line, let’s say, with a few losses. The ownership changed hands four times – one owner would sell, another would buy, each bringing their own vision. And each new owner was surprised to learn that there was an architect (who the heck is this guy?) insisting on certain things… In hindsight, maybe that was predictable, but I wasn’t prepared for it. There were moments that the losses felt irreparable. Over time, I came to accept the fact that life reshapes things differently than we initially plan. By and large, however, I’d say that, yes, the project was realized largely in line with the original ideas. “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov ArchitectsSo, you are satisfied with the result, aren’t you? One thing is certain: I’m relieved that it’s finally complete – the central connecting part is finished, and the entire complex as well. At last, we can see the space that we envisioned back in 2006. Eighteen years ago, it was all just an outline – the specific architecture of the buildings and spaces took shape later on and underwent significant changes at every stage of design. Let’s go over the project’s history briefly, starting with the 2006 competition. I don’t remember all the details anymore, but about 18 teams were competing. The competition invited all the top Moscow-based and international architecture firms of the time. The jury was led by Ilya Lezhava and Vyacheslav Glazychev – two highly respected intellectuals. Ilya Lezhava understood us better than anyone; in a way, he was a mentor to all of us. Both he and Glazychev advocated for preserving the factory buildings, although, to be honest, there wasn’t much architectural value left on the site by then. The competition proposals were split into two major groups: some teams preserved remnants of the Kauchuk factory, while others chose to start from scratch, which also made sense – on an empty site, you have more freedom to explore different possibilities. In the end, the jury selected two winners: “by points”, Yuri Grigoryan’s proposal – favoring preservation – came out on top, while my project, which called for full demolition but offered a compelling spatial concept, was its closest competitor. The development of the territory, occupied by Kauchuk factory. The competition proposalCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSThe final decision was left to the client. Over the next month and a half, they held discussions with both Yuri and me. The preservation option was, on one hand, not very economically viable and, on the other, didn’t fully align with what the developer wanted. In the end, they chose me to develop the master plan, with the condition that certain valuable elements would be preserved. Ultimately, the only part that remained was the façade of the factory’s administration building, designed by Klein, facing Usachevskaya Street, along with the volume of the structure situated immediately behind it. Did the first concept already include the artificial pond? Yes, but it was more of an elongated waterway, like a fragment of a river. It had two banks – one “Asian” and one “European” – almost like in some game of chess. The smaller buildings were clustered in the center, while the taller, more urban ones, were positioned along the edges. In the early stages, for a short period, Evgeny Ace acted as a consultant for the developer. I recently found an old photo of us sitting together, discussing something. It was during those conversations that the idea of the pond and central zone crystallized. We analyzed various iconic public spaces in Moscow, trying to understand what made them popular, and we all agreed that a pond was a key urban-forming element. But we also had to consider the phased construction of the blocks and the fact that they would emerge sequentially. This led to the idea of a cross-shaped composition. I must say, at first, the client was hesitant about including a public urban space inside the complex – “How will we operate it?” they asked, even suggesting that the center should be built up as well. But I insisted: “No, it is imperative that there be an open void in the center”.  “Khamovniki” quarter. Project, 2007Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS “Khamovniki” quarter. Project, 2007Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSAlexander Kuzmin [Moscow’s chief architect from 1996 to 2012 – Ed.] supported this idea and, in fact, backed the project as a whole. He happened to visit our studio just when the main client was there and said, “Great idea, don’t redraw anything – just build it as is.” Some time later, when the concept was practically finalized, approved by the client, and endorsed by Kuzmin, a design code was developed, along with a phased construction timeline. At that point, the idea arose to invite other architects to design some of the buildings – not all of them, just a handful. The developers understood that if too many different architects were involved, it would be difficult for me to maintain a cohesive vision. So they invited Yuri Grigoryan, Vladimir Plotkin, Sergey Tchoban, Ostozhenka, Art-Blya, and Alexey Kurennoi – who was a key figure in Moskomarkhitektura back in those days. Who was easy to work with, and who was difficult? Yuri Grigoryan was the easiest to collaborate with. We share similar views on how work should be done – first and foremost, together, by listening to each other. Also, Yuri liked brick and sculptural forms, just the way I did. I must say, he executed exactly what I had envisioned, yet his work remained distinctly his own, with a fair share of author vision and originality. From the start, I kept sixteen buildings facing the pond for myself, period. I immediately told the client that it was crucial to create a cohesive urban space there, where all key aspects of form, detail, and material interaction would be carefully considered. Our studio handled the entire underground infrastructure, the landscape for the blocks, transformer substations, the community center, and the school. The school was always “my thing” – I expected it to land right into my hands. But, alas, it never did! All the blocks were meant to be connected by a single road to school, which would be passing under a cantilevered structure – a laconic, solid volume designed with the same simplicity as the pond. The entire concept was based on contrast: the residential buildings were architecturally complex, while the school was strikingly simple, yet surprising in its own way. How did you address regulatory requirements? Schools are supposed to have fenced-off grounds, aren’t they? Yes, they are, but here is the thing: there was an entrance from Shibayevsky Drive for those who didn’t live in Garden Quarters, and there was a separate school route – a ringed pathway through all the courtyards via overhead bridges. From this elevated path, the children would descend to a second checkpoint, scan their cards, and enter. There was a staircase and an elevator. The second entrance could also be used for outdoor breaks – it provided an additional recreation area. Yes, two entrances are always more complicated than one, but we resolved all the issues. The school’s boundary ran along its façade. Back in 2007 or 2008, this was a feasible solution. We even passed the design review with it!  The concept for building a residential area in Moscow′s Khamovniki area, 2006Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS View from the central zone of garden Quarters. The “Novy Vzglyad” school as part of “Garden Quarters”, 2020Copyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSCan you remind me why the project was eventually changed? It turned out that the client – by then the second owner of Garden Quarters, the company Inteko – transferred the area under the cantilever, which had been agreed upon as an easement between the school and the public space, into the ownership of the 3rd block. This was done secretly to obtain approval for increasing residential floor area. We only found out years later, when a new client took over the school project. Due to this reassignment, the space under the school’s cantilever lost its easement status, meaning it could no longer serve dual functions – and the cantilever itself became impossible. The new school client then decided to pursue a different, more cost-effective, and simpler project. In my view, the school that was ultimately built didn’t fit into the intended spatial paradigm. It might have been a good, appropriate building elsewhere, but definitely not here. And the quality of construction seems subpar to me – they rushed it. The “School Road” had to be cut short; it no longer leads anywhere because the new school design didn’t account for its existence or any interaction with it. As a result, the space between the blocks “sank” and collapsed conceptually… even though, luckily, it did not ruin the central zone as a whole. And then there’s the 5th block – yet another disappointment. We even proposed our own design for it, but the client at the time rejected it.  “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov Architects “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024. 2nd quarter, the tower designed by SSACopyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov ArchitectsWhat ended up being built there, in my opinion, is atrocious. The worst part is that some people think it’s my architecture, for crying out loud! Just recently, friends called me – they bought an apartment in the 5th block. They say the views from the windows are fantastic, but the layouts aren’t half that great. What went wrong? Well, of course, the views are fantastic – overlooking my square and my buildings. But, yes, things did go wrong because we had no control over that block at all.  Multifunctional residential development in Khamovniki (Quarter 5 of "Sadovye Kvartaly" complex) © Sergey Skuratov ArchitectsCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS Multifunctional residential development in Khamovniki (Quarter 5 of "Sadovye Kvartaly" complex) © Sergey Skuratov ArchitectsCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSBut initially, a community center was planned for the 5th block, right? Yes – offices, a shopping center, some sports facilities. It was meant to be a mixed-use public center with a multi-screen cinema, a large supermarket, a co-working space, and a hotel. It would have formed a unified urban space together with the Usachevsky Market square. Residents could have reached it directly via underground access. There was supposed to be a unified underground space, shared by all residents. All three underground levels were interconnected – it was designed as a real “underground city”. You could get into it in your car, drive underground to the shopping center, take an elevator down with a cart, load your groceries, and drive back to your block. Or perhaps visit your friends in a neighboring block, in warmth and comfort, regardless of the weather. The finishes were top-quality down there, by the way. Originally, a single maintenance service was planned, but when construction started in phases, separate homeowners’ associations formed in each block, and the first thing they did was divide the territory. Now they even have different rates for cleaning services… Sadly, that part didn’t work out. There should have been more restaurants at the lower level by the pond – 10 to 12, like in a good resort town by the water. But in the 2nd block, World Class moved in with a 50-meter swimming pool, taking up a lot of the frontage facing the pond. We had to modify the design to accommodate it. You mentioned an easement. How is land ownership structured in Garden Quarters? Is the land divided between the city and private owners? The entire territory is privately owned, belonging to the residential complex. The public space resulted from our initial agreements with the client at the start of the project. In theory, if the residents of all the five blocks came together and made such a collective decision, they could close off the entire area with a fence – though practically, it would be extremely difficult, almost impossible, due to the spatial layout. But, yes, legally, it’s still possible. We did consider granting the public space to the city through an easement, but we were very wary of that: if we handed it over, the quality of architecture would inevitably be compromised. The city simply wouldn’t have invested as much in landscaping. The space features expensive German-made Klinker brick, Swiss stone, all these precise slopes and verticals. When working on Garden Quarters, did you have any European prototypes in mind, at least to convince the client? Yes, many. We traveled with the clients to European cities – Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Copenhagen – in 2007–2008, studying urban practices, seeing how things actually worked in real life. Our clients were very progressive; they were absolutely fascinated by it all. There were plenty of examples, though not with this exact height and density… Actually, the density in Garden Quarters is quite low – 23.5 thousand m²/ha. By today’s standards, that’s a very low density. However, back then, 18 years ago, we didn’t expect it to become so expensive. We envisioned our complex to be meant for the middle class, not the extremely rich people. At the time, those people lived on Ostozhenka, while our project was meant for the upper middle class. The idea was that these people would love restaurants and social life. We designed a truly European district – where you don’t have to go far from home to find every kind of activity. If you live in London or New York, you live in the city, not some closed-off “reservation”. You step outside into a public square, onto a city street. There’s a pond, kids playing in sandboxes, and right there, a café – you can step into a courtyard, and no one yells at you or kicks you out. We wanted Moscow to have that same level of comfort and openness. But here… people seem to shy away from public life. They write complaints about how to shut down the public area – saying that all sorts of bloggers with cameras keep showing up, filming, doing fashion shoots, and the like. So now, the residents are paying to maintain a space that everyone uses, and they’re not happy about it? Yes, exactly. The costs of upkeep fall on the residents and tenants – including me, since our office is also in Garden Quarters now.  The office of Sergey Skuratov′s architectural companyCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTS The office of Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSCopyright: © Sergey Skuratov ARCHITECTSFor us, it’s easier – if they ever do close the perimeter (which is unlikely), our entrance is on the outer side. The tenants around the pond, though, have it harder. Right now, there are mostly beauty salons, cosmetic businesses… but I think that will change over time as the complex evolves. Today, it’s beauty clinics – tomorrow, it’s restaurants. And restaurants need visitors who can freely walk in from the city. Could the already-built public space be handed over to the city for maintenance? As far as I know, such a prospect is being discussed. Maybe it’s possible. But we had planned to hand it over to the city before – and the city didn’t take it. After all, it’s not just about cleaning services. It’s about maintenance, replanting large trees, replacing Klinker brick, and, most importantly, managing the pond. I don’t think the city will take it now either. It turns out, we created an expensive toy. It’s not that we didn’t think about how exactly it would operate – we did. But we were relying on somewhat different economic relationships, a different demographic composition; on the development of urban planning laws that would allow for more complex stories of ownership and function symbiosis. Perhaps we should have studied European experience more from an economic perspective, looking at the legislative framework. I must also admit that the neighborhoods with public life that impressed us in the Netherlands and Denmark were still arranged in a slightly simpler way. What makes Garden Quarters so complicated as opposed to them? The way functions and ownership are distributed in space, to start with. In Rotterdam, for example, if there’s underground urbanism, it’s clear-cut: the city is above, private property is below. No throughways, no overlapping spaces. Here, in Garden Quarters, everything intersects with everything. You can step out of a private garage on the third basement level and walk directly to the pond side restaurant tables. The six-meter parking wall? It’s fully glazed and retractable.  “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov Architects “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov ArchitectsThis whole project is a dream, in a way, a romantic dream. And we, the dreamers, happened to meet clients who were also romantic dreamers. We didn’t separate boundaries vertically. The public pedestrian areas are literally the rooftops of restaurants and the fitness center. In theory, World Class could maintain its own roof. But the people walking above it aren’t the same ones swimming in the pool or lifting weights. And below it all? A massive three-level parking structure. This allowed us to connect everything beautifully – you can enter the gym from the parking garage and then step right out to the pond. But to slice these three-dimensional solutions into neat legal boundaries? That’s nearly impossible. Honestly, underground urbanism is a huge problem for us. The regulations just don’t work. What did Garden Quarters teach you? Besides the experience of defending your decisions, dealing with the loss of some parts of them, and accepting transformations in a large project? Working with underground urbanism and expansive public spaces integrated into private territory? Underground urbanism has always been part of our projects, both before and after. As has the desire to open up spaces for the city and make it permeable. This is present in our projects before and after, and in the works of our teachers. Garden Quarters is just a stage in the experimentation with multi-level and public spaces within residential complexes. It’s a fascinating topic, but I would say it’s a subject for a separate discussion.  “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov Architects “Garden Quarters”, the public space, 2024Copyright: Photo © Daniel Annenkov / provided by Sergey Skuratov Architects |

|